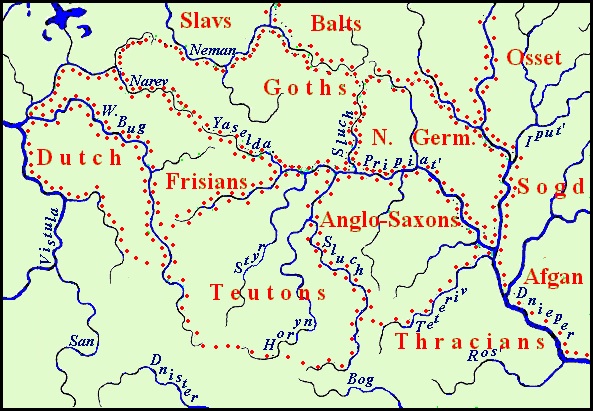

Place Names on the Way of the Germanic Tribes to Scandinavia.

The ancestral home (Urheimat) of the Norsemen defined by graphical-analytical method, was located in ethno-producing area limited by the Dnieper, Pripyat, Berezina, and Sluch (lt of the Pripyat) Rivers (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 76-78

At right: The territory of the Germanic languages in II mill. BC.

Taking into account historical evidence, the location of the ancestral home of the Northern Germanic People, and the possible migration ways of their ancestors to Scandinavia, the search for North German toponymy was carried out on the territory of Belarus, the Baltic States, and northwestern Russia. Explanation of clearly not Slavic names was made using the dictionary of Icelandic language, which is considered as "the Classical Language of Scandinavian race" (An Icelandic-English Dictionary) and Etymological Dictionary of the Swedish Language (HELLQUIST ELOF. 1922). The etymological dictionaries of the English and German languages (HOLTHAUSEN F., 1974; KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989) were used to clarify the meanings of words and of phonological patterns of the Germanic languages as also Online Etymology Dictionary.

Preliminary remark on the phonology.. The sound f was absent in the Slavic languages, Icelandic has this sound which in some cases has evolved from the Germanic b through b. Thus the Icelandic f of this type corresponds to the Slavic b in loan-words from Icelandic. Aboriginal Germanic f, kept in Icelandic, was reflected in Slavic in the khv. Later, thanks to borrowings, the sound f appears in Slavic languages and pronunciation khv is now considered to be vulgar, so in some cases the return to the original f can be.

There is an opinion that any geographical name can be deciphered in several languages. This is not entirely true and is possible for short names, but for long ones, good phonetic matches with a close sense occur in closely related languages, and in languages of different groups it is practically impossible if you do not take into account borrowings. In this regard, with the proven presence of the ancient Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe, a certain difficulty was caused by the separation of the North Germanic and Anglo-Saxon place names. However, in the ongoing research, the decoding of toponyms is not an end in itself, it only serves to confirm that at a certain place at some time there was populated by people speaking the language that allows decoding a sufficiently large number of place names of this area. At the same time, clusters of toponyms or their chains have great evidentiary power, while any isolated names should not be taken into account. In addition, such explanations of place names that correspond to the characteristics of the nearest locality or consist of two logically related parts are more credible.

The search for the concentration of North Germanic place names was carried out for several years, and the discovered indirect data came to the rescue. This painstaking work made me partly agree with the opinion of another researcher:

A bright material culture of the northern appearance, reflecting all aspects of society (urban and rural settlements, funerary monuments, treasures), exists in an onomastic vacuum. Eastern Europe has not preserved a mass toponymy of Scandinavian origin (TOLOCHKO ALEKSEY, 2015: 170).

A. Tolochko is right if only Russia is attributed to Eastern Europe, where North Germanic toponymy, indeed, can only be accidental. However, on the territory of Belarus and Latvia to date, several dozen toponyms of possible North Germanic origin have been found, arranged in a certain pattern. Their complete list is constantly supplemented with new data, the decryptions made are clarified, and errors found are deleted. The current composition of the list is displayed on the GoogleMyMaps map, but the most convincing examples of toponymy interpretations are also given here. In particular, on the territory of Belarus, these may be the following:

Artuki, a village in the Rechytsa district of Gomel Region – Ic. arta, Sw. årta "garganey" (Anas querquedula), a bird, Old Norse ugga, uggi "to fear"

Berkav, a village in Homel Region – Old Sw. biork, Ic. björk "birch".

Berkava, a village in Vitebsk Region – Old Sw. i>biork, Ic. björk "birch".

Bonda, a hamlet in Vishnev community of Smorgon' district Of Grodno Region – Old Sw.bonde "landowner", Ic. bóndi "a tiller of the ground" bónda-fólk "tillers".

Bryniow, a village in Gomel Region – Old Sw., Ic. brynja "armour".

Daugava (Western Dvina), a river – Old Sw. duvin "forceless", "limp", Ic. dvina "to dwindle".

Dowsk, a village in Gomel Region – Old Sw. döfer, Ic. döf, Nor. døve "deaf".

Drybin, a village in Mogilev Region – Old Sw. driva "to dive", "to lead", Ic. drīfa "to drive".

Farinava, a village in Vitebsk Region, Belarus – Old Sw. far "to move", Ic. far "motion, travel", Old Sw. nava, Ic. nöf "nave".

Франополь, villages in the Miory and Postavy districts of Vitebsk Region and the Smorgon district of Grodno Region – Ic. frann "shine, flash"

Gawli, a village in Gomel Region – Old Sw., Ic. gafl "gable-end", Sw. gavel, "end", Norw gavl "gable".

Gerviaty, a town in Astrovets district of Grodno Region – Ic. görva, gerva "equipment, harness", tá "way, road".

Gomel (Homyel), a city in Belarus – Ic. humli, Sw humle, OE hymele ”hop plant”.

Hresk, a town in the Slutsk district of Minsk Region – Ic. hress "hale, bearly", hressa "to refresh, cheer".

Markovo, an agrotown in the Molodechno district of Minsk Region – Old Sw. mark “land, area”, “land plot”, Ic. mark “sign, border, end.”

Markovtsy, villages in the Uzdensky district of Minsk Region. and in the Smorgon district of Grodno Region – like Markovo

Minsk (originally Mensk), the capital of Belorus – Ic. mennska "humanity", mennskr "human", Sw. mänsklig "human"

Myory, a town in Vitebsk Region – Ic. mjór "slim", Old Sw. Mjö- "narrow" in place names.

Opsa, a village and a lake in Brasla district of Vitebsk Region – Ic. wōps "furious".

Pastovichi, an agrotown in the Staryya Darohi district of Minsk Region – Ic. pasta "a type of material"

Radashkovychi, an urban settlement in Molodechno district of Minsk Region – Ic. rætask "to fullfil", Old Sw. rättskaffens.

Randowka, a village in Gomel Region – Ic. rønd "rim, border, end", Old. Sw rand "border, end".

Razeta, a village in the Braslav district of Vitebsk Region – Ic. rá "milestone, boundary sign" (Old Sw. in place names rå), Old Sw.- säte, Ic. setja "place, location".

Rum, villages in the Volozhin district of Minsk Region and in the Rossony district of Vitebsk Region – Old Sw. rum, Ic. rúm "room, place, space".

Rumino, a village in the Orhsa district of Vitebsk Region – like Rum.

Rumische, a village in Myory district of Vitebsk Region – like Rum.

Rymdzyuny , a village in Astravyets district of Grodno Region – Old Sw. rum, Ic. rúm "room, place, space", đjóna "to serve, fit", Old Sw. tjäna "to serve".

Saltanovka, a village in Mogilev district – Old Sw., Ic. saltan "salting".

Skepnia, a village in Gomel Region – Ic. skepna "a shape, form", Sw. skepnad "image", "ghost".

Smargon', a city in Grodno Region – Old Norse smar "small", göng "lobby".

Shaytarava, a village in Vetebsk Region, Belarus – Old Norse skái "to relief" (about pain), tara "war, battle".

Shvakshty, a village and a lake in Miadel district of Minsk Region – Old Norse skvakka "o give a sound".

Svedskae, a village in Gomel Region – Ic. svæđi "open place".

Svirkos, a village in Švenčionys district municipality of Vilnius County, Lithuania – Ic. svíri "neck".

Svir, a village and lake in the Myadel district of Minsk Region. – Ic. svíri "neck".

Varniany, a town in Astrovets district of Grodno Region – Old Sw varna "to warn", Ic. varnan "warning, caution", vörn "a defense".

Vendezh, a village in the Pukhovichi district, Minsk Region. – Old Sw. vænda, Ic. venda "to turn".

Vendelevo, a village in the Minsk district – Old Sw. vænda, Ic. venda "to turn", Vändel, commonplace name in Sweden

Vitebsk, a city in Belarus – Old Sw. hviter, Old Norse hvit, Sw. vit "white" and Old Norse efja "mud, ooze", Sw. ebb, äbb "ebb".

The examples given once again confirm the location of the ancestral home of the Scandinavians and at the same time outline the most likely route of their migration to Scandinavia. Judging by the place names, the Northern Germanic People reached Scandinavia not through Finland but swam across the Baltic Sea approximately from the mouth of the Daugava River. Place names along the banks of this river can mark their path. It is visible in Google My Maps that the Scandinavians moved to Daugava in two ways. One went through Minsk, and the other along the Dnieper River.

On the map, the ancestral home of the Northern Germanic people is tinted in pink, and settlements of Norse origin are marked with red asterisks.

Hydronyms are indicated by blue circles and lines.

The lower density of place names along the banks of the Dnieper suggests that the bulk of the northern Germanic tribes moved westward through Minsk along the modern border of Belarus with Lithuania. The further common route of migrants along the Daugava to the Baltic Sea is marked by the following places:

Sterikāni, a village in Līksnas pagasts, Daugavpils novads, Latvia – Old Sw. styrka, Ic. sterkr "force".

Vandani, a town in Jēkabpils district, Latvia – Old Sw. vænda, Ic. venda "to turn".

Gravas, locality in Jekabpils region, Latvia – Old Sw grafa "pi", Ic. grafa "to dig".

Urgas, a town in Koknese district, Latvia – Ic. urga "a strap".

Ogre, a town in Ikškile district, Latvia – Ic. uggr "fear, apprehension".

Riga, the capital of Latvia – Ic. riga "roughnes of the surface".

Reaching the shores of the Baltic Sea, the Norsemen settled on this space, which could be indicated by place names. However, there are in the eastern Baltic area the place names of Germanic origin to be a lot, as since the XIII century German colonists began to arrive here at the invitation of founded here military orders. In this connection, highlighting the place names of Norse origin is very difficult. More or less positively we may say about the following:

Gravas, a village in Talsi Municipality and a settlement in Limbaži Municipality, Latvia – Old SW. grafa "pit", Ic. grafa "to dig".

Rauna, the district administrative center in Latvia – Ic. raun "a trial, experience".

Sloka, a lake in the town of Jurmala and the town of the same name nearby, Latvia – Old Norse sloka "to slop".

Urga, a village in Braslava parishAloja district, of Aloja Municipality, Latvia – Ic. uggr "fear, apprehension".

Valmiera, the district administrative center in Latvia – Old Norse Valmær, one of the names of the Valkyries, the characters of Norse mythology.

There are different hypotheses about the ancestral home of the Germanic peoples and their migrations to modern habitats. In their proof, only speculative judgments are given that can also be contested speculatively. Toponymy provides specific material that can be refuted only by linguistic methods. It is doubtful that anyone would undertake to do this.