Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe

Currently, there are several unofficial versions of the southeastern border of Europe. The International Geographical Union has not yet made a final decision. Therefore, in this review, all Anglo-Saxon toponymy found in Eurasia refers to Europe, which forms distinct clusters west of the Caspian Sea.

Preamble

By July 2023, I will have interpreted 1,397 place names across continental Europe using Old English. Such a quantity itself surprises me to no small extent, but no one else has shown the same surprise yet. Perhaps nobody believes in such a possibility, believing that my etymologies are chosen to prove my fiction about the Anglo-Saxon migrations throughout Europe. If someone thinks so, then he overestimates my imagination too much, but I would put it to better use. In principle, I understand that all sorts of unusual ideas are, first of all, objectionable, but, surprisingly, no one has tried to independently decipher toponyms that are well known to him and do not have convincing etymologies. However, the accumulation of Old English toponyms in one place could encourage others to search in the nearest area. For example, I gave my interpretations of two place names in Portugal, but did not explain the name of Lisbon for several years. During this time, anyone could try to do this by looking in the dictionary of the Old English language to see how beautiful the name of this city is, but no one came up with such an idea, not even the one who deals with this issue. All this makes one think about how imperfect humans are.

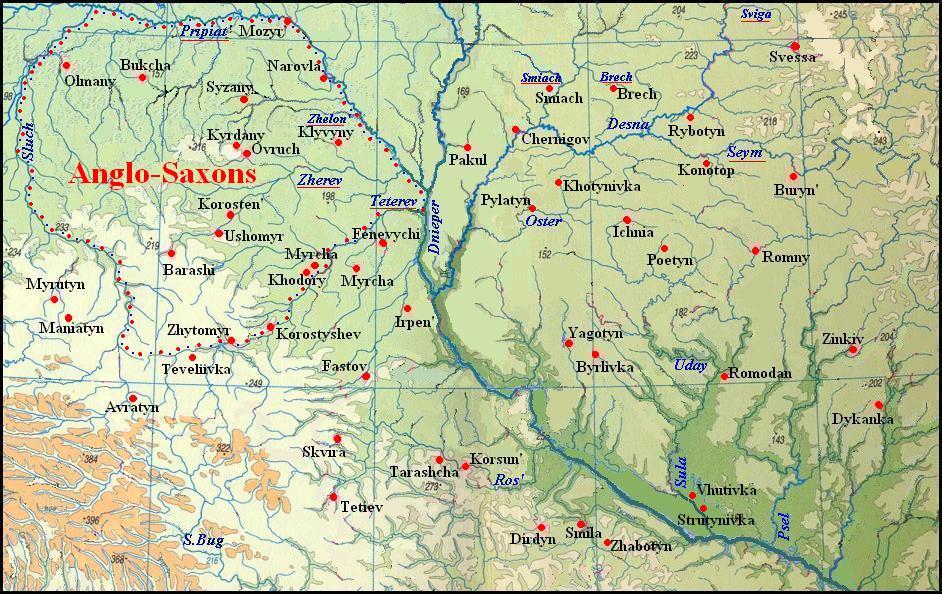

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons was localized by graphic-analytical method in the ethno-producing area between the Sluch, Pripyat, and Teteriv Rivers (see the section Germanic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age). At one time, most Anglo-Saxons migrated to the British Isles, but some of their groups chose other ways. Places of their settlements, both on the ancestral home and on other parts of the continent, have been left in place names which kept to our day. The Anglo-Saxon toponyms were searched among the names of geographical objects, which can not be deciphered using the languages of the local population. The etymological dictionary of the Old English language (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974) was used for this aim, as well as the Anglo-Saxon dictionary (HALL JOHN R. CLARK. 1916). Searching, its methods were improved, and some regularities were revealed, too. As a result, more than a thousand possible Anglo-Saxon place names were found in the space of continental Europe, some of which can be attributed to random coincidences. Some of them have more confidence, which to some extent corresponds to the peculiarities of localities or form clusters or chains that can reflect the routes of the migrants. The complete list of place names is submitted separately, but some regularities and peculiarities in their composition, as well as the most convincing cases, will be given here.

Particularly convincing is the decoding of the name of the village Dydyldino, as part of the urban settlement Vidnoye in the Leninsky district of the Moscow Region, using OE dead "dead", ielde "people". The meaning of the name "dead people" is in good agreement with the existence of a place of burial of people from ancient times. Near the village, there are burial mounds of presumably Old Russian times. In the scribe books from 1627 in the village, there was a church in the name of Elijah the Prophet, whose decay was noted already at that time. According to legend, at the beginning of the 15th century, a female monastery was founded here by the wife of Prince Dmitry Donskoy. At the church, there is the Dydyldin cemetery, currently known in Moscow, about which the following information was found:

Even at the time of the founder of the monastery, the Cathedral Ascension Church became the last resting place for female members from the reigning family. In the cathedral were the graves of the Grand Duchesses, the wives of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, beginning with Anastasia Romanovna and ending with Maria Fedorovna, the mother of Tsarevich Dmitry, who was killed in the town of Uglich. Here were the tombs of the queens and the wives of the kings from the house of the Romanovs. The last burial is dated 1731. Then, niece of Peter the Great (daughter of the half-brother of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich) Praskovya Ivanovna was buried in it (Historical reference on the Official website of the administration of the urban settlement Vidnoye of the Leninsky municipal district)

The coincidence of the strange names of Pucita for a small tributary of the Dniester and a street in the city of Borovichi, Novgorod region in Russia, is striking. What could these two remote areas when nothing similar has been found elsewhere? They have in common that the Anglo-Saxons dwelled here and there at different times and gave the street and the river a name that is well suited in both cases – OE. pucian “to crawl” and tā “stringent, whippy”. A targeted search for Anglo-Saxon place names was crowned with the discovery of their clusters both in the Borovichi region and near a tributary of the Dniester, which only confirmed the confidence.

Place names of Anglo-Saxon origin in Eastern Europe include many names like Markovo, Markove, Markovichi and similar which originate from OE mearc, mearca "border", "sign", "county", "designated space". Germanic people called this word the neighbor community. In Russia, the villages of Markovo were recorded as about one hundred. They also meet in Belarus, Poland, Ukraine, and Bulgaria. Having good phonetic correspondence, the Old English words are well-suited to the names of settlements according to their meaning. It is noteworthy that they are distributed among other place names of Anglo-Saxon origin. Of course, some parts of them, which cannot be identified, could receive a name from a person, Mark, but there should not be numerous. This name was not so popular in Russia, but the toponyms derived from it were much larger in number than others, as it was discovered. For example, even the most widespread Russian name Ivan was used twice less for calling settlements. In Ukraine, a natural proportion seems to be observed – Ivanovka – 120 names, but Markovka and Markov – no more than twenty. The same type includes the place name Mayak, also widespread in Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, which has a Proto-Chuvash origin in a similar meaning: Chuv. mayak "landmark".

There is also a rather large group of place names, which at first glance also come from another not very popular name, Victor. Place names Viktorov, Viktorovo, Viktorovka are found in Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus in the number more than six dozen. Such a quantity is simply unbelievable, given the low prevalence of this name among the Slavs, although some names of settlements may come from it. However, most of them were left by the Anglo-Saxons. OE wīċ "house, settlement" and Þūr/Þōr "God of Thunderer" suit for decryption very well.

In general, when analyzing enigmatic place names, sometimes some similar names, which seem to contain a Slavic root, are surprising, but their form, motivation, and especially an extremely large number make us doubt it. For example, more than fifty of these suspicious place names are based on the word rak “crayfish” (Rakovets, Rakovitsa, etc.). This could be the name of a river or stream in which crayfish live, but in the vast majority, such names refer to settlements, and only a few of them are hydronyms. In this case, an attempt was made to decipher them using the Old English language, in which the words racu "channel, stream" and mentioned above wīċ "house, settlement" were found. The motivation for the name of the village on the riverbank is understandable. In a similar way, two dozen toponyms of Lukovets and similar were formed with OE loca "fencing".

The place names that contain the final morpheme -tyn/-tin/-ten/-den belong to the same type. The fact that in Ukraine several tens of place names have a final morpheme -tyn was noted by Igor Danyluk, one of the readers of my site. At first glance, this morpheme could be an extension of the possessive suffix -yn, but analogous affix types -nyn, -ryn, -byn, and similar rarely occur in Ukraine. In this connection, it was suggested that the word tyn as a component of a complex name has its particular meaning.

The search for the origin of this word in several languages resulted in the most suitable being OE tūn "fence", "field", "court", "house", "housing", "village", "town". The word has matches in other Germanic and Celtic languages. The Slavic word tyn is the old Germanic loan-word in the same sense, though it means only "fence" at present. Earlier, it was used for calling settlements of different kinds, as evidenced by such names as Kozya-tyn, Krivo-tyn, Pravu-tyn, Lyubo-tyn having Ukrainian partial word. It can be assumed that the word tyn in the sense of "village" was also spread among the multilingual population of Ukraine, as there are examples of the adhesion of this word with a non-Germanic and non-Slavic word. For example, the place name Zhukotyn is decoded by Chuv çaka "linden" and this explanation can be plausible as there are a lot of lime trees in the village at present. However, the second partial word of this name has nothing similar in the Chuvash language. The component -tyn meaning "village" has also been used by the Proto-Chuvashes who populated the Carpathians at some time.

Names of settlements with similar formants tyn/tin/ten/den are often found in Central Europe and are available even in Britain, where, in addition, many settlements contain formant town. They may have not only Germanic but also Celtic origin, according to Irl. dun(um) and Gal. dinum. This complicates searching for Anglo-Saxon place names of this type. In this connection, place names with the format den are not considered in most cases as having a priori Celtic origin. A few exceptions were made in cases where only good Old English matches were found for the first part of the word (for example, Dresden, Breddin).

Place-names having the root tyn are extremely common in the Czech Republic such as Týn nad Bečevou, Týn nad Vltavou, Týneček, Hrochův Týnec, Týnišťko, Týniště, Týnec, Týnec nad Labem, Týnec nad Sázavou. Not all of these settlements were founded by the Anglo-Saxons, especially that part of them have Slavic suffixes, therefore they were not taken into account

Below are given some examples of names of possible Anglo-Saxon origin scattered throughout Eastern and Central Europe, which contain the component -tyn/-tin/-ten/-den:

Avratyn, villages in Lubar district of Zhytomyr Region and in Volochysk district of Khmelnytsky Region – OE æfre "continual", tūn "village".

Boratyn, Boryatyn, Boryatynj, about ten villages in different regions of Ukraine, Poland, and Russia – OE bora "son", tūn "village".

Burtyn, a village in Polonne district of Khmelnytski Region – OE būr "a peasant", tūn "village".

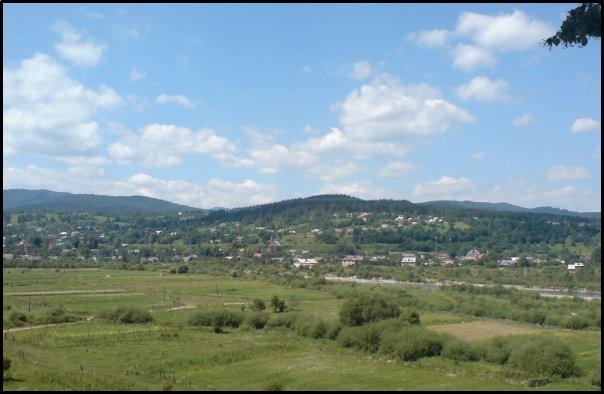

Delatyn, a town in Nadvirna district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region – dǽl, dell "valley", tūn "village". The town indeed is located in a valley (see the photo at left).

Dirdyn, a village near the town of Horodishche in Cherkasy Region – OE đir “a female servant”, tūn "village".

Dresden, the capital city of Saxony in Germany – OE dærst (dræst) „leaven, dregs, refuse“, tūn "village".

Husiatyn, a town in Ternopil Region, the village of Husiatyn in Chemerivtsi district of Khmelnytski Region – hyse "a son", "lad", "warrior", tūn "village".

Maniatyn, a village iv Slavuta district of Khmelnytski Region – OE manian "to prevent", "to protect", tūn "village".

Myrotyn, a village in Zdolbuniv district of Rivne Region – OE mære "border", tūn "village".

Obertyn, a village in Tlumach district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region – OE ofer "over", "high", tūn "village".

Roggentin, a municipality in the Rostock district, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. – OS roggo "rye", tūn "village". The ancestors of the inhabitants of this commune were engaged in agriculture. Its coat of arms is the so-called "lily", which is a modified form of the sheaf (for more details, see Cultural Substratum). Thus, the coat of arms confirms the explanation of the place name.

Rukhotyn, a village in Khotyn district of Chernivtsi Region – OE rūh "raw, rough", tūn "village";

Rybotyn, a village in Korop district of Chernihiv Region – OE rūwa "cover, covering", tūn "village";

Skowiatyn, a village in Borshiv district of Ternopil Region – OE scuwa "shade", "protection", tūn "village";

Wettin, a town in the Saalekreis district of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany – OE wæt "wet, moist", tūn "village".

A Special part of names of this type contains the stem Khotyn (Hotin). It is generally accepted their Slavic origin, but more likely that the initial forms of the word consist of two Old English words heah "high" and tūn "village". This interpretation is completely justifiable at least for the city of Khotyn in the Chernivtsi Region since it is located on the high bank of the Dniester. Names of this type are found in several countries:

Ukraine – Except for the city of Khotyn, three villages in Rivne Region have the same name, also there are two villages Khotynivka in Chernihiv and Zhytomyr Regions, and the village of Khoten' in the Khmelnytskyi region, and the village of Khotin' in Sumy region. The last two names may indeed have Ukrainian origin.

Belarus – the village of Khotynychi (Brest Region).

Russia – the village of Khotynets (Oryol Region).

Poland – the village of Chotyniec in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship.

Slovakia – the village of Chotín in Komárno District in the Nitra Region.

Czech republik – the village of Chotyně in Liberec District and the village of Chotyněves n Litoměřice District in the Ústí nad Labem Region.

No less common toponyms are Konotop and similar, found in Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and Russia:

Ukraine – the city of Konotop in Sumy Region, the villages of Konotop in Shepetivka district of Khmelnytski Region and in Horodnia district of Chernihiv Region, a village of Konotopy in Sokal district of Lviv Region.

Belarus – the villages of Konotop in Rudsk rural selsoviet of Ivanovo district, in Bobrik selsoviet of Pinsk district of Brest Region, and Narovla district of Homel Region, the villages of Konotopy in Zhabinka district of Brest Region and Kapyl district of Minsk Region.

Poland – the villages of Konotop in Gmina Kolsko, Nowa Sól County, Lubusz Voivodeship, Gmina Drawno, Choszczno County, West Pomeranian Voivodship, Gmina Drawsko Pomorskie, West Pomeranian Voivodship, two villages of Konotopa in Gmina Ożarów Mazowiecki, Warsaw West County and Gmina Strzegowo, Mława County, Masovian Voivodeship, two hamlets of Konotopa in Gmina Brańsk, Bielsk County, Podlaskie Voivodeship and in Gmina Ruda-Huta, Chełm County of Lublin Voivodship, the village of Konotopie in Gmina Kikół, Lipnowo Couny of Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship

Russia – the village of Konotop in Kromy district of Orel Region.

The names look completely Slavic and have a transparent interpretation (Rus. kon' "a horse", topit' "to sink"), but at the same time, reasonable doubts arise not only because of their large number but also because of the interpretation itself. Not only horses but also other cattle, for example, oxen (Slav. vol), could sink in the marshland, however, such names as Volotopes are absent. In addition, in Poland, where they are most of all, these place names stretch as a strip among other Anglo-Saxon ones, marking the way of the Anglo-Saxon migration. This was the reason to look for another explanation for them. Only Old English could provide such an opportunity. The first part of the name comes from OE cyne-, which is found only in compound words and means "royal" (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 67). This word, as well as king, German König and others similar Germanic words meaning "king" originate out of Gmc. *kunja "kin", "noble origins" (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 397). OE. cyne- is a later modification of the Old Germanic, which is phonetically better suited to the names of this type. The second part of the name goes back to OE topp "top, the summit". Thus, the original name could sound like Kunyatop, and the Slavs rethought it as horse-sinking. Settlements with this name could be the residence of the tribal elite. And a few other toponyms contain the same Gmc *kunja:

Two villages Konyatyn in Sosnytsia district of Chernihiv Region and Putyla district of Chernivtsi Region, the village of Konyatino in Cherepovets district of Vologda Region, the village of Konyatinskaya in Rostov-Minsk district rural settlement, Ustyansky district of Arkhangelsk Region. – Gmc. *kunja "kin", "noble origin" and OE tūn "town".

The village of Konyatin in the Chernihiv region is located in the center of the sites of the Sosnitsa culture, which creators were the Anglo-Saxons (see on the map below). Judging by the deciphering of the name, it could be the residence of a local tribal leader. Archeological excavations in this village could confirm this assumption. The spread of the monuments of the Sosnitsa culture also confirms the decoding of place names using the Old English language (cf. the maps further)

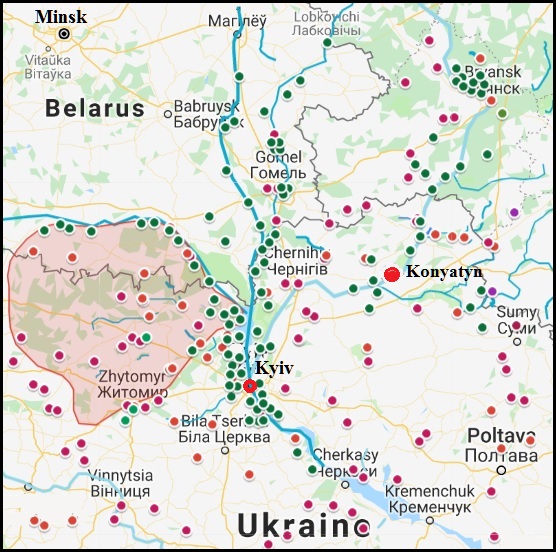

The sites of the Sosnitsa culture (green) and Anglo-Saxon place names (red).

Data on archaeological sites were taken from Archeology site

The map also shows the village of Konyatin as the Anglo-Saxon tribal center.

Another large group of names at first glance does not cause doubts about their Slavic origin. In Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, Poland, and the Czech Republic there are about three dozen similar names Okno, Okna, Oknitsa with Ukrainian variants Vikno, Viknyny, etc. Already their very number gives reason to doubt that all of them come from an ordinary Slavic appellative okno "window", which has no example, say, in Russia. Searches in different languages convinced me that there is nothing better than OE āc "an oak" for explaining the origin of these place names. This word together with the suffix en could form an Old English adjective ōken, well suited to the name of the locality.

The Urheimat of Anglo-Saxons was at first populated by the ancient Italics (forebears of the Latinians, Oscans, and Umbrians), then by the Anglo-Saxons, and subsequently by the ancestors of the Slovaks. In more recent history, this space was inhabited by the Slavic tribe of Drevljan, whose capital was the fabled town of Iskorosten. Scribes have tried "to slavicize" the name of this town, now called simply Korosten, which no doubt comes close to the name used in ancient times.

The town is located above the Usha River, which meanders along granite banks. Here the English language allows us to etymologize the name of the town, using O.E. stān, “stone, rock” and the Cornish care, “rocky ash” presented in the place name Care-brōk (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 43). The root care can also be found in the name of the town of Korostishev, located on the Teteriv’s rocky left bank. If the second part of this toponym derives from O.Eng. sticca, “stick, staff”, the place name can be taken as a whole to mean “ashen stick”. This, at first glance, a convincing explanation of the names Korosten and Korostishev is doubtful. The fact, that the mountain ash (Fraxinus ornus) does not grow in this locality, does not mean much, because common ash tree is very spread here and the transfer of names of plant species from one to another is a known phenomenon. Much more objection has the explanation by using the word care, which can have a Celtic origin (Ibid).

The name of another town is connected to rocks as well: this is Ovruch, located in the Slovečan-Ovruč Hills on the upper left bank of the Norin’ River. Eng. of rock may be explained as “on rocks” as well as “near rocks,” or "rocky”.

At left: Anglo-Saxon place names on the ancestral homeland of the Anglo-Saxons (its borders are marked with red dots) and out of it on new places of settlements.

As a whole, we can etymologize nearly forty local place names using the English language. Some of them are listed below:

Barashi, a village in Yemelchine district of Zhitomyr Region – OE bǽr “abandoned, bare”, ǽsс “ash-tree”.

Fenevychi, a village at the bank of the upper Teteriv River – OE fenn "swamp", wīc “house, village”.

Khodory, Khodorkiv, and Khodurkiv, villages in Zhitomyr Region – OE. fōdor “food, feed”.

Kyrdany, a village near Ovruch – OE cyrten "beautiful”.

Latovnia, a river, the right tributary (rt) of the Ten’ka, rt of the Tnia, rt of the Sluch – OE latteow "leader”.

Mozyr’, a city, Belarus – OE. Maser-feld to N.Gmc. mosurr "maple" (AEW).

Narovlia/ the town on the right bank of the Pripjat’ River – OE nearu “narrow” and wæl “pool, source”.

Olmany, a village in Belarus, southeast of the town of Stolin – OE oll “to insult, abuse,”mann, manna “a man” man “fault, sin”.

Prypiat’, a river, rt of the Dnieper – OE frio "free", frea “lord, god”, pytt “a hole, pool, source”.

Rikhta, a river, lt of the Trostianycia, rt of the Irsha – OE riht, ryht “right, direct”.

Syzany, a village south of the Homel’ Region in Belarus – OE. sessian “to grow quiet”.

Ushomyr, a village in Korosten district of Zhytomyr Region on the Uzh River – O.Eng. meræ "border", that is "the border along the Uzh river". Cf. Zhytomyr.

Zhelon’, a river, rt of the Low Prypiat’ – OE scielian “to part”.

Zherev, a river, lt of the Už, and r Žereva, lt of the Teteriv, rt of the Dnieper – O.Eng. gierwan "to boil” or "to decorate” (both meanings suit the toponyms, depending on the character of the respective river).

Zhytomyr, a city, – O.Eng scyttan “to close, lock” or scytta “shooter” from which comes the name of the Scythians, who were good archers, and meræ "border", that is "protecting border" (from the Scythians). Cf. Ushomyr.

The Anglo-Saxons migrated from their Urheimat in different directions, which is demonstrated by place names. English roots in the name of the Irpin’ River (Old Ukrainian Irpen’) are especially ly transparent.

At right: The Irpen' River.

Photo from the site Foto.ua

This river has a wide boggy valley that should have been boggier in ancient times. Therefore OE *earfenn, compiled by OE ear, meaning 1. "lake" or 2. “ground”, and OE. fenn “bog, silt”, could have a sense of “sludgy lake” or “boggy ground”. The name of the city Fastiw (Fastov) has arisen from OE fǽst “strong, fast". OE swiera “neck”, “ravine, valley” suits for decoding the name of the village of Skwyra on the Skwyrka River, if k after s is epenthesis, ie inserted sound to give greater expression to the word. In favor of the proposed etymology says the name of the village of Krivosheino is formed from Ukrainian words meaning “curved neck” which can be a linguistic calque of an older name. The village is located on the river bend.

Other place names of Anglo-Saxon origin in the country west of the Dnieper can be mentioned above Awratyn, Dyrdany, and as follows:

Vorzel, an urban-type settlement in Kyiv Region – OE. orgel "proud", "haughty". Cf. Vorgol.

Korsun’ of Shevchenko, a town in Cherkasy Region, two villages in Belorus, one in Donetsk Region (Ukraine), one in Orel Region (Russia) and near-by rivers having the name Korsun', the village of Korsyni in Volyn' Region and the village of Korsiv in Lviv Region – In his dictionary, F. Holthausen cites OE cors "cane, rush" present in place names but believes that it is borrowed from Celtic (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974:58) what else needs to be proved.

Myrcha, villages, one west of the town Dymer in Kyiv Region, another south of the town of Malin in Zhitomyr Region and one else in Transcarpathia on the border with Slovakia – OE mirce "murky, dark, black".

Smela, a town, Cherkasy Region – the name of the town can have as Slavic as an Anglo-Saxon origin. (Eng smile or smell) but OE smiellan "to strike, hit, burst" suits best of all taking in consideration the diphthong in the old variant of the city's name.

Tal, a river, rt the Teteriw, lt of the Dnieper – OE dǽl “valley”.

Tetiew, a town, Kiev Region – OE tætan “to gladden, coddle”.

Place names being decoded by means of Old English out of the Anglo-Saxon Urheimat but on the space of the East-Trzciniec culture, which belonged to the Germanic people, affirm the migration of Anglo-Saxons eastward across the Dnieper and to the southeast, where the Sosnitsa culture was spread as a variant of the Trzciniec. In the basin of the Upper Dnieper, there are many such river names as Rekta, Rekhta, Rikhtaand at the same time the same river can be called Resta, Rista:

The plurality of variants and the generally large number of these hydronyms in the Upper Dnieper region indicate a sort of their autochthony (TOPOROV V.N., TRUBACHOV O.N. 1962, 204-205).

Experts believe that the etymology of all these names is very difficult because neither in Slavonic, nor in the Baltic, nor in Iranian languages there is good correspondence. As a variant, it is proposed Lith riešutas, rieksts "walnut, hazelnut", but the connection of these words with all forms of hydronyms is problematic (ibid, 204). On the contrary, OE riht, ryht "right, straight" and ræst, rest "quiet, calm" are well suited phonetically and according to the meaning. With the help of the Old English language on the Left Bank, in the Desna and Seym basin, one can find the interpretation of many other unclear toponyms:

Brech, a river, lt of the Snov River, rt of the Desna – OE brec “sound, noise”.

Bryansk (chronicle Bryn' – according Tatishchev), a city – OE bryne "fire".

Buryn’, a town, Sumy Region – OE burna “spring, source”.

Byrliwka, a village, Drabiv district, Cherkassy Region – OE byrla "body".

Dykanka, atown, Poltava Region – OE đicce "thick", anga "thorn, edge".

Ichnia, a town, Chernihiv Region – OE eacnian "to add".

Iwot, villages, one to the east of the town Novhorod-Siverski and another in the north of Bryansk Region in Russia, Ivotka, Ivotok Rivers – OE ea "river", wōð "nois, sound".

Kharkov, a city – OE hearg "temple, altar, sanctuary".

Khvastovichi, a village in south of Kaluga Region in Russia – OE fǽst "strong, fast, firm" and īw, eow "yew-tree".

Klewen', a river, rt of the Seym River – OE cliewen “a clew”.

Nerussa, a river, lt of the Desna – OE nearu "narrow", essian "to waste". Cf. Svessa.

Resseta, a river, rt of the Zhizdra, lt of the Oka – OE rǽs "running" (from rǽsan "to race, hurry") or rīsan "to rise" and seađ "spring, source".

Romodan, a town, Myrhorod district, Poltava Region – OE rūma "space", OE dān "humid place".

Romny, a town, Sumy Region – OE romian “to seek, aim”.

Senkiw, a town, Poltava district – OE sencan “to dip, sink”.

Swessa, a river, lt of the Ivotka, lt of the Desna, the town of Svessa in Sumy district – OE swǽs “peculiar, pleasant, beloved”, essian "to waste".

Sviga, a river, lt of the Desna – OE swigian “to be silent”.

Sev, a river, lt of the Nerussa, lt of the Desna – OE seaw “sap, moisture”.

Seym, a river, lt of the Desna – OE seam "side, seam".

Smiach, a river, rt of the Snov, rt of the Desna – OE smieć “smoke, steam”.

Sozh, a river, lt of the Dnieper – OE socian “to boil”.

Ul, a river, lt of the Sev River, lt of the Nerussa, lt of the Desna – OE ule “owl”.

Volfa, a river, lt of the Seym – OE wulf “wolf”.

Vorgol, villages in Krolevets district of Sumy Region and Izmalkovo district of Lipetsk Region – OE. orgol "proud", "haughty". Cf. Vorzel'.

Vyatka, a river, rt of the Kama – OE. wæt "humid, moist", -gê "gau, district".

Vytebet', a river, lt of the Zhizdra River, rt of the Oka – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, river-bed".

Yagotyn, a town in Kiev Region – OE iegođ "a little island".

Quite a lot of place names with the final formant – tyn among the considered at the beginning of this section are located in Western Ukraine. In this case, other place names here may have Anglo-Saxon origin too. For example, as follows:

Bar, the district center in Vinnytsia Region – OE. bār "boar".

Khodoriv, the district center in Lviv Region – OE. fōdor “food, feed”.

Korsyni, a village in Rozhyshche district of Volyn' Region – see Korsun'.

Korsiv, a village in Brody district of Vinnytsia Region – see Korsun'.

Rashkiw, two villages in Ukraine, one of them in Ivano-Frankivsk Region and another in Chernivtsi Region, one village in Moldova. In addition, the city with similar names are available in Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina – OE ræscan "to tremble, shake". This meaning is not suitable for the names of settlements, especially since there are quite a few of them. Most likely, the Old English word is related to the Old Icelandic raska "sway", "move", "displace". The last two values are quite suitable for the names given by the migrating people.

Rykhtychi, a village in Drohobych district of Lviv Region – OE riht, ryht "right".

Svirzh, a river, lt of the Dniester River – OE swiera "neck", "ravine".

Strypa, a river, lt of the Dniester River – the name of the river can have as Anglo-Saxrjy and Teutonic origin (OE. strīpan "to stripe", MLG. strīpe “a stripe”}.

Vinnytsia, the region center – OE winn "toil, trouble, hardship".

Wendychany, a village in Mohyliv-Podilski district of Vinnytsia region – OE wendan "to turn", cinn “chin”.

Win’kiwtsi, the district center in Vinnytsia Region – OE. winc "to wink", hīw "appearance, form".

The list of the place names of the Anglo-Saxon origin while further research is complemented and corrected, what requires a permanent correcting illustrative maps and it's pretty hard work which also harm the quality of cards. In this regard, the new additions and removal of random coincidences will be placed in the system Google Map (see below)

On the map most part of the Anglo-Saxon place name is indicated by dark-red points. The settlements of Markovo, Markino, and similar have purple color. Hydronyms are marked in azure.

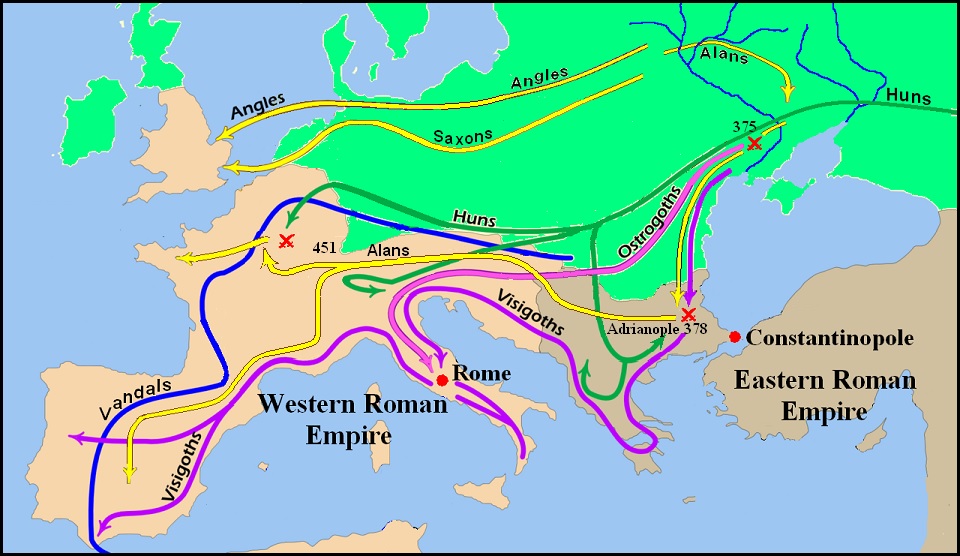

Red space is the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons. The yellow – Sarmatia. The red asterisks mark the battlefields at Adrianople (378) and on the Catalaunian Plains (451) which in the Alans took part.

The map also shows the village of Konyatyn, Chernihiv region, which was supposedly the residence of a local tribal leader.

The map shows that the densest cluster of Anglo-Saxon place names is located on the ancestral homeland of the Anglo-Saxons and on the adjacent territory of Right-Bank Ukraine. There is quite a lot of place names on the Left Bank. Mostly they coincide with the territory of the spread of the Sosnitsa culture, a local option of Trzciniec culture. Right-bank Ukraine, outside the ancestral homeland of the Anglo-Saxons, has no reliable binding for toponyms, therefore some of them similar to Old English words could be accidental. However, nevertheless, there is a certain pattern in their location, because outside of Ukraine they stretch towards Germany in two lanes, one of which goes along the Carpathians and through the Moravian Gate (the height of the pass is only 310 meters) enters Bohemia, and the other passes through central Poland.

A good evidence of the Anglo-Saxons stay in Poland can be decoding name of the village Czorsztyn in Lesser Poland Voivodeship as "jutting rock" (OE. scorian "to jut out", stān "stone, rock"). In this village, there is really projecting rock on the shore of the reservoir formed by the river Dunajec (see. the photo at right). Similar words are or were present in German (OHG scorra "rock", Stein "stone"). In addition, there are several settlements in Poland, which contain the component sztyn (Wolsztyn, Falshtyn and possibly others), all which can have as German (Teutonic) as Anglo-Saxon origin. The Anglo-Saxon origin may be assumed more justified only if they are part of a chain or cluster of names. Nevertheless, many place names in the band passing through Central Poland have a clear Anglo-Saxon origin. For example, the name of the village of Kornati can be interpreted using OE. corn "grain", ate "oats".

When looking for Anglo-Saxon toponyms on the territory of Ukraine, it was noted that some of them have matches in Central Russia. In addition to the above-mentioned villages of Boryatyn in the Bryansk, Penza and Vologda regions, three villages in Kaluga and two villages in the Lipetsk region have the names Baryatino of the same origin. The name of the Ukrainian city Chortkiv, which is explained with OE ceart "wasteland, wild public land" and gief "gift", corresponds to the names of the Russian villages of Chertkovo in the Rostov, Penza and Vladimir Regions. The same word ceart could be reflected in other languages or dialects as "kart" and we find it in the Ukrainian toponym Karatamish, Kartamysh, and in the names of three Russian villages of Kartmazovo in the Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod and Vladimir Regions.

These cases prompted a targeted search for Anglo-Saxon place names in Central Russia. They were conducted very cautiously because the toponyms of non-Slavic origin could be left by the northern Germans or Balts. For example, such names as Fishovo can have both Anglo-Saxon and North Germanic origin (OE fisc and OIcl fiskr "fish"), and such as Ievlevo, Ievkovo can be both Anglo-Saxon and Baltic (OE. īw, eow "yew" and Lith., Let. ieva "bird-cherry"). As for the North Germanic place names, the area of their spread is mainly located on the territory of Belarus and Latvia, where they were left by the North Germanic people during their migration from the ancestral home to Scandinavia (see the section North Germanic Place Names in Belorus, Baltic States, and Russia. At the same time, the presence of the Varangians in Eastern Europe has displayed in place names very insignificantly:

Nowhere in Russia was there such Scandinavian colonization as in England and Iceland. In addition, the Swedes had no reason for mass emigration to the opposite shore of the Baltic Sea. In their own country, there were rich and fertile areas (SAWER PITER, 2002: 241-242)

Of course, there are undoubtedly North German toponyms in Russia, for example, the name of Lake Seliger is in good agreement with OIcl. seligr, sjaligr "beautiful". Accordingly, close to them located place names can with a great likelihood be North Germanic too.

If we talk about the Baltic toponymy, then according to the experts' testimony, it is absent in the territory east of Moscow and north of the Upper Volga, being widespread in the Smolensk, Pskov, Kaluga, Moscow, Orel Regions (VASILIEV VALERIY L. 2015: 175). A number of toponyms of supposed Anglo-Saxon origin were also found in these areas and they can not be attributed to the Baltic. And, as it turned out in the process of searching, many common names of settlements in Russia, which do not have a convincing interpretation in Russian, are deciphered precisely with the help of Old English. First of all, they include, except the already mentioned Markovo (97 cases), such names: Levkovo (25), Churilovo (24), Shadrino (24), Ryazanovo (22), Fatyanovo (18), Boldino (11), Burkovo (10). These names have such explanations:

Levkovo, Levkovka, Levkov a.o. – OE. lēf "weak", cofa "hut, cabin".

Churilovo – there was not found any reliable interpretation of the toponym in Russian, allegedly originating out of the name Churilo, which itself has no explanation. The high prevalence of the place name suggests that it should be based on a commonly used word and such is proposed by OE. ceorl "a man, peasant, husband", which corresponds to Eng. churl.

Shadrino – some of the names may occur from the dial. shadra “smallpox”, but their prevalence raises doubts about this interpretation for the overwhelming majority of cases. Usually, names with negative meaning are very rare. M. Vasmer does not consider the origin of this word, therefore it can be assumed that it originates from an OE sceard "maimed, chipped" taking into account the metathesis of consonants. Another meaning of this word is "plundered". Such a name could be given to the settlements of the local population ravaged by the Anglo-Saxons. You can also consider OE sceader from scead "shadow, protection".

Ryazanovo – the name may be partially assigned to settlements by people from the Ryazan region, and the name Ryazan itself, which occurs 5 times in Russia, can be of Slavic origin, although there is no certainty about this. You can keep in mind the OE rāsian “to survey”, which could be used during the resettlement of people when they have to find a suitable place to stop.

Fatyanovo – OE. fatian «to get».

Boldino – OE bold "house, home" is good suitable by meaning and phonetically. So could be called the individual estates of landowners.

Burkovo – OE burg "borough".

The main part of the toponyms of Russia of Anglo-Saxon origin is concentrated in the Vladimir, Yaroslavl, Tver, Vologda, Kostroma, Ivanovo, Nizhny Novgorod and Novgorod Regions. Here are the most convincing examples of the Anglo-Saxon place names of these places:

Berkino, villages in Moscow and Ivanovo Regions, Berkovo, a village in Vladimir Region – OE berc "birch".

Firstovo, two villages ib Nizhniy Novgorod Region and one in Moscow Region – OE fyrst "firsy".

Fundrikovo, a village, Semyonov district, Nizhny Novgorod Region – OE fundian "strive for, wish", ric "domination, government, power".

Fursovo, seven villages in Kaluga, Ryazan, Tula, and Kirov Regions – OE fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble".

Kotlas, a town in Arkhangelsk Region – OE cot "hut, cabin", læs "pasture".

Linda, a village in town district Bor, Nizhny Novgorod Region, Lindy, a village, Kineshma district, Ivanovo Region OE lind "linden".

Moscow (Moskova in chronicle), the capital of Russia, Moskva, villages in Tver and Novgorod Regions – OE mos "bog, swamp", cofa "a hut, pigsty".

Murom, a city, Vladimir Region – OE mūr wall", ōm "rust".

Ryazan, a city – 1. OE rāsian "explore, investigate". 2. OE rācian "господствовать".

Suzdal, a town, the center of the district, Vladimir Region – OE swæs "peculiar, pleasant, beloved", dale "valley". Cf. Sösdala, a locality in Sweden.

Shenkursk, a town, Arkhangelsk Region – OE scencan "to pour, give to drink, present", ūr "richness, wealth".

Yurlovo, three villages in Moscow Region – OE eorl "noble man, warrior", "earl".

The highest density of Anglo-Saxon toponyms is observed on the territory of the former Vladimir-Suzdal principality. From time immemorial, these places were inhabited by Finno-Ugric tribes, and at the end of the first millennium AD, the Slavic tribe of Vyatichi advanced here too. The Vyatichi according to the chronicles were the most backward of all the Slavs and did not even create their own state in their homeland in the Oka basin, so it is surprising that the newly created Vladimir-Suzdal principality quickly seized the lead from Kyiv. Even Russian historians are amazed at this. In particular, V.O. Kliuchevskiy wrote that there is no clear answer to the question of where the new Upper Volga Rus' grew up (KLYUCHEVSKY V.O. 1956: 272). If, however, to agree that the most ancient cities of this region were founded by the Anglo-Saxons, it must be assumed that they were who laid the foundations of statehood here, uniting under their domination of disparate native tribes. However, during the heyday of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, the Anglo-Saxons, apparently, were already fully assimilated by more large local population.

We see a similar picture in the steppes of Ukraine, where the Anglo-Saxes have become the ruling elite in the union of Sarmatian tribes of different ethnicity (see sections The Sarmatians and Alans – Angles – Saxons). Due to the repeated population change in the Northern Black Sea Coast, local toponymy developed already in historical times, but quite a few ancient geographical names of different origins were preserved on the Donbas, among which you can find Anglo-Saxon, for example:

Kramatorsk– OE crammian "to press something into something else". The previous name Kram was added by the name of the Torets River.

Holmivs'kyi, a town in Donetsk Region – OE. holm «wave, sea, water»

Hladosove (Gladosove), a twon in Donetsk Region – OE glæd «shining, gracious, kind», ōs «pagan divinity».

At left: The Mius River

Photo of Оlga GOK. Rostov-on-Don.

Dyliivka, a twon in Donetsk Region – OE. dyle «dill».

Korsun', a village and a river in Donetsk Region – OE cursian «to plait».

Mius, a river flowing into the Sea of Azov – OE meos "swamp, bog".

Vergulivka (Verhulivka) i Perevals'k district of Luhans'k Region – OE wergulu «nettle».

In Donbass, in some places, since the Bronze Age, people have mined copper ore. The Anglo-Saxons, moving along the right bank of the Seversky Donets, stopped here for a long time and took the mining and processing of copper into their own hands, as a result of which they achieved economic and, accordingly political power. Obviously during the invasion of the Huns at the end of the 4th century AD. the numerous Anglo-Saxon population of Ukraine was divided into two parts, one of which, in alliance with the Germanic tribes, moved west and reached Spain, and the other chose the path north to the upper reaches of the Volga, but over time, both of them disappeared from the face of the Earth, although they left their traces in toponymy.

A.K. Matveev, analyzing the substrate toponymy of the Russian North, gives the toponyms Pelda and Randoga, which reflect the Fin. pelta "field" and ranta "shore", but "indicate the presence of Germanic elements in the Northern Finnish languages". However, OE feld and rand are phonetically closer to them. (MATVEYEV A.K. 1969: 53). At the same time, OE ōga "fear" is well suited for the second part of the name Randoga. Further, Matveev cites the toponyms Dvina, Vaga, Modlon and Svid and considers them Indo-European (ibid, 54), but there is no interpretation for them in Russian. They, too, can be etymologized with the help of Old English.

That part of the Anglo-Saxons that moved west became known in history under the name of the Alans. In addition to the names of the Alanian leaders, the Germanic origin of Alans is confirmed also by friendly relations of the Alans with the Germanic tribes of Goths, Vandals, and Suevi (Suebe). These relations are supposed to have some more serious explanation than a situational alliance of the tribes of different languages without a purpose and reason. Obviously, the common Germanic ethnopsychology helped Alans quickly find mutual understanding with the Goths and Vandals, than with other people. In 378, the Alans in alliance with other Gothic disparate units, under the general command of Fritigern participated in the defeat of the Roman army at Adrianople.

The Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Alans migrated under the pressure of the Huns in search of new lands for settlement. They have not moved a single stream, but each of these people is in their way and only temporarily united for military purposes. Even the Alans, moved out at least in two groups, making it difficult to establish their migration routes. As always, during the migration of peoples, their way has been marked by settlements, where a part of the migrants remain to stay for various reasons. This phenomenon was observed by the ancient migrations of the Proto-Chuvashes, Cimbri, Angles, and Saxons. The trail of the Alans to Adrianople is marked by the city of Tulcea (OE tulge "strong, solid") in Romania, the cities of Bulgaria Varna (OE wearnian "to warn, be careful") and Burgas (OE burg "borough"). The chain of place names that may mark the path of further movement of the Alans after Adrianople consists of the following:

Haskovo, a village in southern Bulgaria – OE hassuc "wet, row grass", Eng. hassock. Better OE has "hot", cofa "cave". There are hot springs in this area.

Rashkovo, a village in Sofia Region, Bulgaria – OE. ræscan "to tremble, swing". Most likely the Old English word had another meaning, as it does in its related Old Norse raska, which is translated as both "to tremble", and as "to rock", "to displace". This meaning is much better suited for names of settlemants of migrants. Cf. Raška, Raškovići, Raškovci.

Berkovitsa, a town in Montana Province, Bulgaria – OE berc "birch".

Raška, a town, the center of Rashka district in Serbia – see Rashkovo

Sige, a village in the municipality of Žagubica, Serbia – OE sige 1. "lowland", 2. "victory".

Raškovići, a village in the municipality of Goražde, Bosnia and Herzegovin – see Rashkovo

Berkovica, a village in Bosnia and Herzegovina – OE berc "birch".

Raškovci, a village in the municipality of Doboj, Bosnia and Herzegovina – see Rashkovo

Vinkovci a city in eastern Croatia – OE wincian "wink".

Valpovo, a city in eastern Croatia – OE hwelp(a) "whelp".

Szekszárd, a city in Hungary, the capital of Tolna county – OE sex, siex, "six", eard "land, place, settlement".

However, judging by the density of the Anglo-Saxon toponymy (see Google Map above), most of the Alans first moved to the Carpathian Mountains, and then, after crossing the Carpathians, advanced to Transylvania. This path among others is marked by the following place names:

Rakhiv, a city in Trancarpathia – OE. raha "chamois".

Bârsana, a village in Maramureş County, Transilvania, Romania – OE. bærs, bears "perch".

Rohia, a village in Maramureş County, – OE. raha "chamois".

Brad, a city in Hunedoara County in the Transylvania region – OE. bræd "width".

Arad, the capital city of Arad County, Romania – OE. ared, arod "quick, rapid".

A further way of the Alans, through the territory settled by Germanic tribes, is difficult to trace because of the similarity of local dialects to Old English. However, it is known that the Alans together with the Vandals and Suevi reached Spain, where they founded their kingdom, and after the destruction of the kingdom by the Visigoths, they along with the Vandals crossed into North Africa. While driving through France, the Alans also founded their settlements and their way to Spain across southern France can be marked as follows:

Bourg-en-Bresse, a commune, the capital of the Ain department,– OE burg "borough, town", bræs "ore, bronze".

Lyon, a city in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region – OE lion "to lend", "to preserve".

Lemps, a commune in the Ardèche department – OE. limpan "to belong", "to be fit".

Gignac, a commune in the Hérault département in the Occitanie region – OE. geagn "against", gegn "right".

At left: Alanian kingdom in Spain.

The map of Wikipedia.

The Alanian kingdom existed in Spain for a short time (409-426), but Alanian presence here is reflected in a few place names, using the Old English language for decryption, for example:

Alenquer, a municipality in the Oeste Subregion in Portugal – there is an explanation of the name as "Alanian temple" involving OG kerika "church". The name can be given by Visigoths, but this word is not fixed in the Gothic language, and there was in OE cirice "a church".

Lisbon, the capital of Portugal – OE liss (liđs) "grace, love", bōn "entreaty". Liss as a part of the name is present in many other place names in France, Netherlands, and Britten.

Logroño, the capital of the province of La Rioja in Spain – OE lōg "place", rūne "witch".

Madrid, the capital of Spain – the first mention of the city is preserved in the Arab transcription: مجريط (Majrīṭ, pronounced as maʤrit). There are several versions of the origin of the name, but we can substantiate an Alanian origin: OE māg "bad, shameless" and rīđ "a stream, river". Madrid is located on the small Manzanares River.

Murcia, a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital of the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia – OE murcian "be unhappy, complaining".

Utiel, a municipality in the comarca of Requena-Utiel in the Valencian Community, Spain. – OE ūtian "to banish, steal".

It should be said that the Germanic idea of the ethnicity of Alan is not new. This view was held by Franz Altheim, Norman Davies included the Alans to the East Germanic tribes together with the Swabians, the Lombards, the Burgundians, the Vandals, the Gepids, the Goths (DAVIES NORMAN. 2000. 241).

Some evidence of friendly relations between the Alans and Goths provides also archaeology. While the Slavic tribes of the Zarubintsy culture were displaced by the Sarmatians from the Forest-steppe Dnieper Land between the Tyasmyn and Stugna rivers, "the relation the Sarmatians and the bearer of the Cherniakhiv culture in the 2nd-4th centuries was totally different than the situation between the Sarmatians and Zarubintsy people". The Sarmatians were involved in the creation of the south-western region of the Cherniakhiv culture, and their funerary rites are like Chernyakhiv ones (BARAN V.D., Otv. Red., 1985: 9-10). The Chernyakhiv culture was created by the Goths who came to the Black Sea but it's cultural Sarmatian traits were superstrate, "that is, they are superimposed on the already established culture in the process of its spread to new territories" (GUDKOVA O.V. 2001:39). In this connection, we can assume that the cultural interaction of the Goths and some part of the Sarmatians was due to the similarity of their languages and customs preserved since the Germanic community.

Taking all this into account, we have to make a final conclusion that only a part of the Alans could be the Germanic-speaking people (during when the Great Migration had gone to Central Europe and then in Spain and Africa, and, as it turned out, subsequently into the British Isles). In other words, the name Alans could hide as German-speaking, Iranian-speaking, and even Turkic-speaking tribes of the Northern Black Sea region, caused by the transfer of the name of a dominant tribe to the other participants of the union of different tribes.

Quite recently, the long-known connections between the cycle of legends about King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail with the Scythian-Sarmatian world have been summarized. In 2000, a book was published wherein authors try to explain these relationships (LITTLETON C. SCOTT, MALCOR LINDA A. 2000). One of these connections was noticed as one of the first, and later Dumezil recalls it. In the multinational epic of the peoples of the Caucasus about the Narts, a described episode of the death of one of the heroes named Batraz has a parallel to the death of King Arthur. Both die from the fact that their swords are thrown into the water.

The one of the book "From Scythia to Camelot": Morte D'Arthur by Daniel Maclise

The book was controversial in the scientific world, as evidence from the authors is based on analogies that maybe not be so convincing. The reasons for these connections in influencing a small number of the Yazyges who served in the Roman legions during their campaigns into Britain in the 2nd century on the culture of the indigenous Celtic population look unconvincing too. The Celts, hostile to the Romans, could not have close cultural contacts with them, the more it is doubtful that they were subjected to the cultural influence of the Yazyges. Such an influence could have been made by new numerous migrants, namely by the Alans, who undoubtedly had common cultural elements with the Iranian-speaking population of the Northern Black Sea Coast, but historical data on the relocation of the Alans to Britain are absent. Although Linda Malcor explains the name of Lancelot, one of the knights of King Arthur as “(A)lan(u)s à Lot” (Alan of Lot, the area in Southern Gaul, where at one time massed Alans). One would assume that other Alans came to Britain with Lancelot.

If the Alans arrived in Britain from Southern Gaul, the more they could do it from Northern Gaul. It is known that Flavius Aetius, the honored leader, the actual governor of Gaul, known for his victory over the Huns on the Catalaunian Plains in 451 near the city of Châlons-en-Champagne, gave Armorica area (north-west France) into the possession to Alanian King Eochar (otherwise Goar). It is known that Eochar with a part of the Alans did not follow the king Respendial to Spain and stayed in central France.

Invasions of Roman Empire by Goths, Huns, Vandals, and Anglo-Saxons in 4-6 cen AD

In the subsequent time there were several rulers named Alan in Armorica and, in addition, the local place names testify that the peninsula of Brittany and the adjacent area were inhabited by the numerous Alan horde:

Brest, a city in the Finistère département in Brittany – OE. breost "breast".

Kerlouan, a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany – OE. ceorl "man, peasant", own "own".

Landéda, a commune in the Finistère department – OE. land "land", ead "wealth, happiness".

Landerneau, a commune in the Finistère – OE. land "land", earnian "earn, win, gain".

Landivisiau, a commune in the Finistère – OE. land "land", eawis "apparent".

Locarn, a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department of Brittany – OE. loc "lock", ærn "house".

Rostrenen, a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department of Brittany – OE. rūst "rust, red", ren "house".

A chain of place names (deciphered by the use of Old English language) stretches from the battle area of the Katalaun fields to this cluster of place names. It includes the following settlements: Sézanne, Bernay-Vilbert, Rambouillet, Brou, Berne-en-Champagne, Laval, Cornillé, and Rennes. It is significant that the name of Rambouillet is deciphered by Old English as "sheep's wool" (OE ramm "ram", wull "wool"). Obviously, the local population has long been engaged in sheep breeding here and subsequently there was created a royal sheepfold where a fine-fleeced sheep rambulie breed was bred.

English monk Bede the Venerable in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People asserted that the tribes of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes arrived in Britain in the 5th after Roman legions left it. He reports the names of such leaders as Angles Hengist and Horsa (BEDE, XV), which can be translated from Old English as "a stallion" and "a horse". These names are suitable for horsemen, the Alans. However the inhabitants of Jutland, from where, according to Bede, Angles came, were not riders as also other Germanic people. The Bede described these events in after nearly 150 years and obviously used scanty data about the ancestral home of the Angles of the Roman historian Tacitus (ca. 56 – ca. 117 A.D.).

There is in the English county of Oxfordshire on a hillside near the town of Uffington, a strange figure by length of 110 m and in the form resembling a horse. The mysterious figure is made by filling ditches with broken chalk; its origin is unclear. The prevailing view is that the figure is of Celtic origin and this is proven, among other things, by similarity of the strange head of the figure to images on Celtic coins of the first cen. AD. However, with careful study it turned out that there is overlapping of two different figures – a horse and a dragon (or a snake) (BOTHEROYD SILVIA und PAUL F. 1999: 416). It can be assumed that the original figure of the dragon was later turned into the figure of a horse. It is not excluded that this was done during the reign of King Alfred the Great as is also supposed. In this case, the figure could be modernized by Alans riders which had the horse as a symbol of worship borrowed from the Iranians (which were a part of the multinational Sarmatian alliance).

Uffington White Horse. Photo from Wikipedia.

In principle, the similarity between the ethnonyms of the Angles and the Alans can indicate their common origin. The name of the tribe of the Ρευκαναλοι (Reukanaloi) (i.e., the "Light" or "Wild" Alans) renders of a possible metathesis in word Alan. If n in this ethnonym sounded like ng (ŋ), then the transformation of "Angl" in "Alan" would be quite possible (angloi → aŋloi → alŋoi → alanoi). This explanation assumes the German origin of the word.

The German tribe of Anglii has been known since Tacitus' time. The preferred etymological theory deduces this name from *angula “hook", supposedly because the country inhabited by them had a curved shape. Another theory, namely the Turkic origin of ethnonym, is more suitable in terms of semantics. Old Turkic oğlan (ohlan) "a son, boy, young man" had another meaning, namely, "a rider" (Chuv. dial. yulan "a horseman"). The name of the light cavalry (Pol. ułani, Eng. Uhlans) is arisen from this Turkic word. This plausible explanation encounters phonetic difficulties of which overcoming is tentative. The root oğ is represented in Turkic languages by only a few derivative words, but by itself has no sense. We can assume that it is a variant of the root oŋ (oŋğ) having several meanings – "a pat", "right", "light, convenient", "to improve ", i.e. oğlan originally could exist in the form oŋğlan and it gave angl- and alan-. Attempts to connect the ethnonym Alan with the Turkic oğlan have been known for a long time, but they are considered questionable (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 73), for reasons unknown.

The Alans, having moved to the left bank of the Dnieper, were in close contact with Iranian tribes for a considerable time and could contribute to the formation of a shared cultural environment. How much the Angles and Saxons were involved in this is difficult to say. Most likely, elements of the Sarmatian culture were brought to Britain by the Alans. In the north of France, in the Calais area, deciphering them using the English language, there are several toponyms: Berck, Bernay-en-Ponthieu, Rambures, etc. The distance from here to the island of Britain is only one step, not without reason, the name of the Passa de Calais is translated from French just so. In good weather, the Alans could repeatedly safely cross the island long before the invasion of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. When the Vikings began their predatory attacks on Normandy in the 9th century, it was already populated by people speaking the French language, because by the middle of the 10th century, they had adopted the religion and language of the French (SAWYER PETER. 2002: 11), that is, the Alans were absent there. William the Conqueror went on a campaign from the mouth of the Somme River near Calais. It is not to exclude that the Angles and Saxons also might have used this same way. Still, a sea voyage from Jutland to Britain for people who did not have a long tradition of navigation would be a very risky venture.

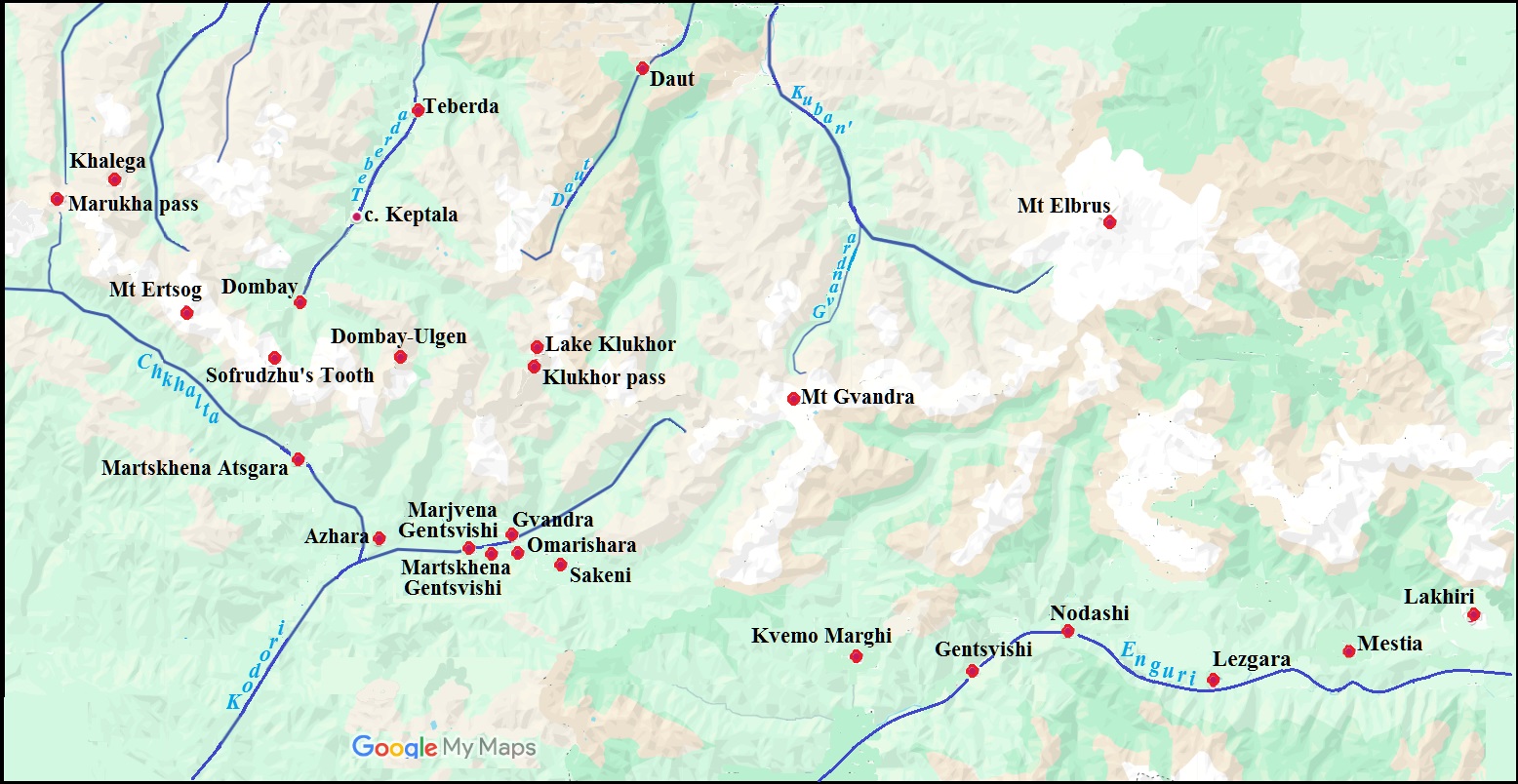

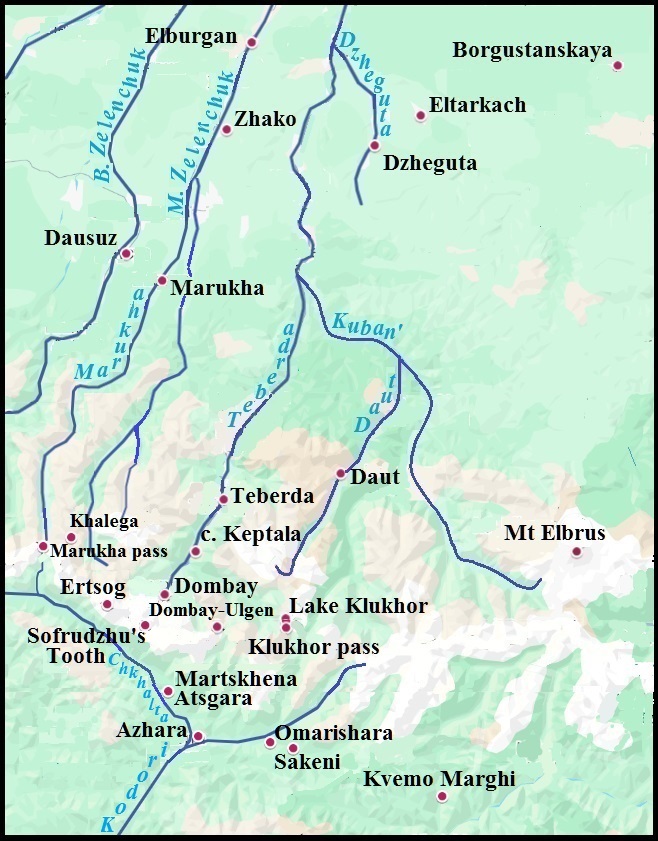

Of course a part of the Alans remained in the North Caucasus and this is evidence by local place names (see the map at right).

Righ: Anglo-Saxon toponymy in the Azov region and the North Caucasus.

Place names marks the path of the Alans from Donbass to the foothills of the Caucasus and their settlement in Caucasian Alania. The most convincing examples are given below:

Yeya, a river flowing to the Azov Sea and originated names from it – OE. ea "water, river".

Sandata, a river, lt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don River – OE. sand "sand", ate "weeds".

Bolshoy and Malyi Gok (Hok in local pronunciation), rives, rt of Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don – OE. hōk "hook".

Guzeripl' (Huzeripl' in local pronunciation), a settlement in the Maikop municipal district of the Republic of Adygea – OE. hūs "house", "place for house", rippel "undergrowth".

Baksan, a river and a town in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE. bæc "back", sæne "slow".

Mozdok, a city in North Ossetia and villages in the Kursk and Tambov Regions – OE. mōs "food", docce "sorrel".

Klukhor pass, a pass on the Voenno-Sukhumi road at an altitude of 2781 m through the Main Caucasian Range – OE hlǣw, hlāw “hill”, “mountain”, horh “dirt”, “mucus”.

Mount Elbrus, mountain peak in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE äl "awl", brecan "to break", bryce "fracture, crack", OS. bruki "the same", , k assibilated in s. Elbrus has two peaks separated by a saddle.

Elbrus

Photo by the author of the essay "My trip to Elbrus"

Elbrus is part of a cluster of Anglo-Saxon place names found in the territory of the medieval state of Alania (see Alans, Alania and Svaneti). Below is an explanation of these toponyms:

Borgustanskaya – OE beorg "mountain", west “west'.

Dausuz – OE deaw “dew”, swǣs “trusted, special, dear, loved”.

Daut – OE deaw “to dew”, -ed is the Past Participle suffix.

Dombay – OE dumb “dumb”, ā “always, forever”.

Dombay-Ulgen – OE dumb “dumb”, wealg “tasteless, bland, disgusting”.

Dzheguta – OE ge- is a prefix (with, together), gyte “downpour, flooding, pouring”.

Elburgan – OE el “foreign, alien”, <beorg "mountain".

Eltarkach – OE el “foreign, alien”,

Ertsog, a mountain – OS herro “lord”, tiohh "gang, troop".

Keptala – OE ceap “buying, selling, trading”, tala, tela “well, appropriate, right, very”.

Khalega – OE hāleg, hǣlg “holy”, ea "water, river".

Klukhor – OE hlǣw, hlāw “hill”, “mountin”, horh “dirt”, “mucus”.

Kuban’ – OE kū “cow” bān “bone”.

Marukha – OE mær “nightmare ghost” uht(a) “twilight”.

Sofruszhu, the mountain, its peak, resembling a bird's beak, is called "Sofrudzhu's Tooth" – OE scio “cloud, sky”, frio free, noble”, giw "vulture”.

Teberda – OE đōhe “clay” beorht “glittering”.

Zelenchuk – OE selen “tribute, gift” cūgan “oppress”.

Zhako – OE geac “cuckoo".

On the southern slopes of the Main Caucasian Ridge, several place names form a chain along the banks of the Chkhalta River and the upper reaches of the Kodori River.

At some point, some of the Alans crossed the Marukh Pass and descended the Marukh River into the Chkhalta Valley. Moving further, they reached its mouth and crossed into the Kodori Gorge. Along the way, they founded the following settlements:

Martskhena Atsgara – OE āge “property. possession", gāra "foothills". Martskhena from Geo. მარცხნივ "left".

Azhara – OE āge “property. possession", āre “honor, grace, favor"; "propriety, privilege".

Marjvena and Martskhena Gentsvishi – OE a-cwencan “to extinguish, vanish", wīsce "meadow". Marjvena from Geo. მარჯვენა "right".

Gvandraa mountain and village – OE ōm/ōme “rust", risc "rush", āre "propriety, privilege".

Omarishara – OE cwene “woman", đrea "threat".

Sakeni – OE sacian “to argue", sacu "fight".

Kvemo and Zemo Marghi – OE mearh “horse". Kvemo from Geo. ქვემო "lower", Zemo from Geo. ზემო "upper". It is interesting that a specialist in the topography of the Caucasus, writing about the road from Teberda to the Tskhenis-tsgali River (the Horse River) [BLARAMBERG JOHANN. 2010].

Gentsvishi – OE a-cwencan “to extinguish, vanish", wīsce "meadow".

Nodashi – OE neod “wish", ǣsce "investigation, claim".

Lezgara – OE leas “free, single", gara "foothills".

Mestia – OE mǣst “most", ea "river".

Lakhiri – OE leah “forest", ierre "erring".

Ushguli – OE wæsc "washing", gūl "reed".

Aylama – OE eġe (ġ = Gmc j) "fear, terror", lama "sick, weak”.

Tsana – OE cian "gills".

Tevresho – OE tierwe "tar".

Glola – OE gleo "joy", la "see!"

Skovi – OE scu(w)a "shadow", "protection".

Oni – OE wana "shortage".

Anglo-Saxon place names on both slopes of the Main Caucasian Range.

The decipherment of the name of the Kodori River using Old English (OE codd "pod" ōra "bank") suggests a certain cultural influence on the local population. The upper reaches of this river are inhabited by the Svans, whose main settlement area is located in the upper reaches of the Inguri. The name of this river may also be of Anglo-Saxon origin: OE enge “narrow”, wǣr “splashing water”. In addition to place names, other facts testify to the presence of Anglo-Saxons among the Svans. Many of the Swans have light hair, which distinguishes them from the Georgians. They call themselves "shnau", which is reminiscent of Old English snāw "snow" [Ibid]. The Anglo-Saxons should have dissolved among the Svans, but some traces of Old English should have been preserved in the Svan language.

In general, the distribution of Anglo-Saxon place names in the North Caucasus corresponds to the territory of the Caucasian Alania (see map below).

The list of Anglo-Saxon toponyms is constantly updated, including with the help of readers. Alexander Tverdokhleb drew my attention to the name of the village of Odrinka in the Kharkiv region. In search of the etymology of the name throughout Europe, 13 toponyms were found containing the component odr-. All of them are among other Anglo-Saxon ones, here are some of them with the proposed interpretation:

Odrynka, a village in Kharkiv Region, Odrinka, villages in Brest Region (Belarus) and in Kaluga Region (Russia) – OE. eodor "hedge, surround, enclosure", inn :"dwellng, house". The meaning "enclosed dwelling" is very well suited to the name of the settlement, which confirms its Anglo-Saxon origin.

The names of villages of Odrinki in the Rivne Region(Ukraine), of Odrino in the Smolensk Region, of Odrina in the Bryansk Region, the name of the lake (and the village?) Odrino in the Pskov Region, (Russia), the names of villages of Odrintsi in the Dobrich and Khask Regions (Bulgaria), the name of the hill, and museum (Odrinhas) in the south of Portugal have the same origin.

The names Odra, Odry and similar ones in Poland, the Czech Republic, Croatia and Slovenia originate only from OE eodor "wattle fence, fence" .

It is possible that several names Ordynka in Russia have the same origin during metathesis.

Doubts about the Old English origin are caused by the presence in the Slavic languages of the less common words odr, odrina and similar in the meanings of "bed", "scaffold", "shed" and others. The available assumptions about their origin are very different, and at the same time, kinship with OE eodor "hedge" is not excluded (VASMER MAX. 1971: 123-124). We should not talk about kinship, but about borrowing, because similar words in other Germanic languages are derived from Old Germanic *edara "fence", the origin of which is not considered (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR 1989: 123-124). Despite the borrowing, which can be put in the same row as the word tyn (see above), some of the place names discussed here may be of Slavic origin. To distinguish them from the common list, additional data (archaeological, historical, etc.) are needed.

The ambiguity of the origin of other German. *edara makes it possible to speak of its origin from Old Turkic *otar, which in different languages has the meanings 1. "pasture", 2 "barnyard", 3. "farm", 4. "village", 5. "flock" (SEVORTYAN E .V.1974: 487-488). In the Germanic languages, the word must be borrowed from Proto-Chuvash (Chuv. utar "apiary", "hamlet") given the assumption that "the word does not belong to the ancient part of the Turkic vocabulary, because it is not found in the written documents" (IBID: 488). It is not found because it was common in Bugarish and other languages of the western part of the common Turkic territory that did not leave written evidence.

The Full List of the Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe