Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe

From the text of the Old English poem "Widsith" it can be concluded that the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons was in Eastern Europe, and studies of ethnogenetic processes using the graphoanalytical method have confirmed this fact (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 77-78).

At right: First lines of "Widsith". Photo from Wikipedia

A series of articles on the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe was written several years ago, but historians did not pay much attention to this topic. Perhaps someone is interested in this, although there may be another explanation. Historians are accustomed to working with historical documents and do not delve into linguistics unless necessary. However, the traces left by the Anglo-Saxons should still be in historical documents.

For example, among other things, we can talk about the monetary unit "schelyagh" mentioned in the early chronicles, in which the Slavic tribe of Vyatichs and Radimichs paid tribute to the Khazars.

At left: The Khazar "Moses coin". Photo from Wikipedia

The similarity of this name to the name of the Western European coin "shilling" attracted the attention of many historians, and various explanations were given to this riddle.

In particular, in one of the works, after a thorough analysis of historical and linguistic materials, it was assumed that the chronicler was joking, using the name known to him figuratively (ZUCKERMAN C. 2018: 459). However, this was not a joke, because the Anglo-Saxons were at the head of the Khazar Khaganate (see Khazars) and, of course, used their language in the administrative sphere: OE. scilling "silver coin". Next, we will talk about other traces left in Eastern Europe

In 1215 Magna Carta Libertatum (“Magna Carta”) was adopted in England, which laid the foundations of human rights in the state and which is still in effect. 800 years ago, the Anglo-Saxons showed such political maturity, which some European nations don’t have so far. It may seem that the democratic spirit is congenital in the Anglo-Saxons. But it is not so. At the time of the Charter adoption, they already had almost two thousand years of active history and great political experience. The fact is that the history of the Anglo-Saxons began in Eastern Europe since the ancestral home of all Germanic peoples, determined by the graphic-analytical method, was located in the upper reaches of the Neman River north of the middle reaches of the Pripyat (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 44). In their ancestral homeland and subsequent migrations, the Anglo-Saxons founded settlements, which often retained their original names to the present day. Toponymy opens the curtain on some details of their ancient history. For example, the name Akhtyrka can be interpreted using OE. eaht “advice, counil, consideration, reasoning” and rice “power, government, kongdom”. From this, we can conclude that the practice of limiting power by democratic methods has developed among the Anglo-Saxons since ancient times. In Russia, there are four settlements with this name (there were five) and in Ukraine there is a city called Okhtyrka. This name cannot be deciphered in any other language.

After their resettlement on both banks of the Pripyat in ethno-producing area, formed by its tributaries, the initial Germanic languages were arisen (ibid: 77-78).

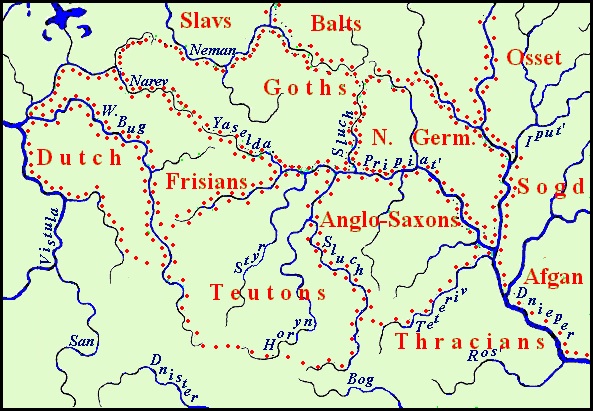

At left: The space of the Germanic languages in II BC.

In particular, the Old English language, which gave rise to the English and Saxon dialects, was formed in the area between the Teterev, Pripyat, and Sluch rivers. We call this area the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons. The rest of the Germanic tribes had their settlements along other tributaries of the Pripyat. And in the basin of the left tributaries of the Dnieper lived different Iranian tribes. That was four thousand years ago.

The presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe is reflected in many place names. The names of the seven settlements Bibirevo in Russia and the name of the village Dydyldino in the Moscow Region are most convincing:

Bibirevo – OE. by: "a group of houses" (in place-names) (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 39), and by:re"barn, hut" (ibid: 40). We find a combination of these words in the names of villages in the Smolensk Region, in the Zapadnodvinsky and Krasnokholmsky districts of the Tver Region, the Ivanovsky district of the Ivanovo Region, the Pereslavsky district of the Yaroslavl Region, the Novorzhevsky district of the Pskov Region and in the name of a former village on the territory of modern Moscow.

Dydyldino – OE dead "dead", ielde "people". The meaning of the name "dead people" is in good agreement with the existence there of a cemetery from ancient times (in detail see Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Russia)

This suggests that the Anglo-Saxons came from their ancestral home to Russia. Other place names of Anglo-Saxon origin indicate their settlement in different directions, both along the banks of the Dnieper and to the west and east of them (see the section Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe ). There are a lot of geographical names in East Europe, which decryption using the Old English or Old Saxon languages can be confirmed by the features of the surrounding terrain. Especially the Irpen, Mius, Wolfa, Witebet Rivers etc have transparent Anglo-Saxon explanation. For example, the Irpen River has a broad swampy flood plain, so earfenn, composed by OE ear 1. “a lake” or 2. “earth” and OE. fenn “swamp, silt”, can be translated for the name of the Irpen as "muddy lake" or "wetlands". This interpretation fits more because the river floodplain had to be more swampy in ancient times than now.

At right: The Irpen River.

Photo from the site Foto.ua

There is on the right tributary (rt) of the Irpen the town of Fastow. This name, clearly not Slavic, obviously originated from the OE fǽst "strong, hard, fast". The name of the city of Zhytomyr can be explained as "protecting border" (from the Scythians) based on OE meræ "border" and scyttan “to close, lock” or scytta “shooter” from which comes the name of the Scythians, who were good archers. In total, more than a thousand place names have been found in continental Europe, which can have Anglo-Saxon origin. Of these, three-quarters are located in Eastern Europe. Below are just some of the most convincing examples from The complete list.

Avratyn, villages in Volochisk district Khmelnytski Region and Lubar district of Zhitomyr Region – OE ǽfre "continual", tūn "village".

Boratyn, three villages of this name in Ukraine – in Sokal district of Lviv Region, in Lutsk district of Volyn Region, and Radyviliv district of Rivene Region. The village of the same name is in Subcarpathian Voivodeship of Poland – OE bora "son", tūn "village".

Boryatino, three villages in Russia in Kletnya district of Bryansk Region, Sheksna district, Vologda Region, Shemysheyka district, Penza Region, Russia – OE bora «son», tūn «village».

Bryansk, a city in Russia – OE bryne "fire".

Farafonovo, villages in Oryol, Novgorod Regions, and Udmurtia, a village Farafonovka in Tver Region – OE faran "to drive, go", faru “journey”, fōn "to take, begin, do something".

Fenevychi, a village at the bank of the upper Teteriv River – OE fenn "swamp", wīc “house, village”.

Kyrdany, a village in Zhitomir Region – OE. cyrten “nice”.

Myrutyn, a village in Slavuta district of Khmelnytski Region – OE mære "border", tūn "village".

Resseta, a river, rt of the Zhizdra River, lt of the Oka River – OE rǽs "running" (from rǽsan "to race, hurry" or rīsan "to rise") and seađ "spring, source".

Rikhta, a river, lt of the Trostianycia River, rt of the Irsha River – OE riht, ryht “right, direct”.

Romodan, a town in Myrhorod district and a village in Lubny district of Poltava Region, Ukraine, a village in Alekseevskoe district, Tatarstan, Russia – OE rūma „space”, OE dān „humid, humid place”.

Romodanovo, a town in Mordovia, villages in Rybnoye and Starozhilovo district of Ryazan Region, a village in Glinka district of Smolensk Region, Russia – OE rūma „space”, OE dān „humid, humid place”.

Seym, a river, lt of the Desna River – OE seam "side, seam".

Wolfa, a river, lt of the Seym River– OE wulf “wolf”.

Worgol, a village in Izmalkovo district of Lipetsk Region – OE. orgol "proud", "haughty".

Wytebet', a river, lt of the Zhizdra River, rt of the Oka River – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, river-bed".

Yagotyn, a town in Kiev Region – OE iegođ „a little island”.

Zibrovo, villages in Serpukhov district, Moscow Region, Odoyevo district, Tula Region, and Dolzhansk district, Oryol Region, Russia - OE sibb "kinship, clan", "peace", rōw "quiet, calm".

Ziborovo, a village, Zolotukhino district, Kursk Region, Russia - OE sibb "kinship, clan","peace", rōw "quiet, calm".

Ziborovka, a village, Shebekino district, Belgorod Region, Russia - OE sibb "kinship, clan","peace", rōw "quiet, calm".

Judging by the place names, some Anglo-Saxons moved to the left bank of the Dnieper and settled there, displacing Iranian tribes. The Sosnitsa variant of the Trzyniec culture can be associated with them. Also, judging by the place names, to the south, namely on the banks of the Sula, Psla, and Vorskla, the Mordovian Moksha tribes had their settlements, which pressed the Iranians from the east. The Bondarikha culture, which existed between 1200 and 800 BC, was widespread here, associated with the previous Maryanovskaya culture, sites of which are also found on the Desna, Seym, Sula, Vorskla, North. Donets and Oskol (BEREZANSKAYA S.S. 1982: 41). The Bondarikha culture goes beyond the Maryanovka culture between the Desna and Sula Rivers. Lebedovskaya culture, which evolved from the Sosnitsa one, was disseminated later here. Over time, the Anglo-Saxons drove Mordovians beyond the Sula River, and perhaps also assimilated their remains, as reflected in otherwise unexplained lexical correspondences between the English and Mordovian languages (see "The Expansion of the Finno-Ugric Peoples ").

The Mordovians are associated by many scientists with the tribe Budinoi described by Herodotus. This assumption has some justification and decoding the name of Budins using Old English confirms it. Βουδινοι, ie Boudinoi, perhaps even "Wudinoi", according to Herodotus, were residents of the forest country. In this case, Eng wooden suits by meaning and phonetically perfectly. A similar word was not noted in Old English but it had widu, wudu "tree, forest" therefore wuden could exist.

Listing peoples inhabiting Scythia in order from west to east, Herodotus called the Nueroi the second after the Thracians-Agathyrsians. He points out that they left their homeland and settled among Budinoi (IV, 105). OE neowe, niowe means "new", and comparative adjective neower "more new" could be used for calling newcomers. Anglo-Saxons could not call themselves newcomers, so it is logical to assume that such a name could be given by the Anglo-Saxons, who moved to the left bank of the Dnieper earlier. These Anglo-Saxons can be connected with the Melanchlainoi, which were named by Herodotus next to the Neuroi and were placed by him to the north of the Royal Scythians and he explained their name as "dressed in black" (Gr. μελασ "black"). However, it is an Old English name, as ancient Angles had a proper name Mealling, originated from OE a-meallian "to get furious" (see HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 216), which together with OE hleonian "to protect" was used by the newcomers for calling their relatives. One might think that they were especially militant. This interpretation is confirmed by the opinion of Buynov, who associates with the Melanchlens the military-aristocratic elite of the population of the forest-steppe part of the Seversky Donets basin, i.e. the area located north of Royal Scythia. The reason for such a distinction is a special elite subculture attested by the burial mounds in the Karavan group of the Lyubotinsky burial ground, the Korotychansky, Protopopovsky, Pesochinsky, and Staromerchansky barrows (BUYNOV Yu.V. 2008: 14). Thus, the Neuroi, and Melanchlaeni, and the Royal Scythians are not ethnonyms, but the names of individual social groups of the Anglo-Saxons (in detail see Royal Scythia and its Capital).

Moving from the Sosnitsa culture space to the north-east, a part of the Anglo-Saxons settled in some time the actual Moscow, Vladimir, and neighboring Regions and even advanced further north-east and north to the shores of the White Sea. Evidence for this we have in the toponymy of these places:

Berkino, villages in Moscow and Ivanovo Regions, Berkovo, a village in Vladimir Region – OE berc "birch".

Dydyldino, a village, Leninskiy district, Moscow Region – OE dead "dead", ield "people, men".

Firstovo, two villages i Nizhniy Novgorod Region and one in Moscow Region – OE fyrst "first".

Fundrikovo, a village in Nizhniy Novgorod Region – OE fundian "strive for, wish", ric "domination, government, power".

Fursovo, seven villages ib Kaluga, Ryazan, Tula, and Kirov Regions – OE fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble" (the plant Genísta).

Kotlas, a town in Arkhangelsk Region – OE cot "hut, cabin", læs "pasture".

Linda, a village in the town district Bor od Nizhniy Novgorod Region, Lindy, a village in Ivanovo Region – OE lind "linden".

Moscow (Moskova in chronicle), the capital of Russia, Moskva, villages in Tver and Novgorod Regions – OE mos "bog, swamp", cofa "a hut, cabin".

Murom, a town in Vladimir Region – OE mūr "wall", ōm "rust".

Ryazan, a city – 1. OE rāsian "explore, investigate". 2. rācian "rule, lead".

Shenkursk, a village in Arkhangelsk Region – OE scencan "o pour, give to drink, present", ūr "richness, wealth".

Suzdal, a town, the center of the district, Vladimir Region – OE swæs "peculiar, pleasant, beloved", dale "valley".

Yurlovo, thre villages in Moscow Region – OE eorl "noble man, warrior".

The Aglo-Saxon expansion was directed as well to the southeast, so they got to Donbas. A cluster of Anglo-Saxon place names was found between the cities of Kramatorsk and Stakhanov north of the town of Debaltseve just near deposits of copper ore. People have mined it here since the Bronze Age. There was a powerful mining and metallurgical center in Eastern Europe composed of about thirty copper mines. Melting copper from local ore is uneconomical at present but copper deposits could still be unexhausted in Scythian times. People settled in the immediate area to profitably engage in mining ore. One of the major mines was not far from the railway station Kartamish. This name can be explained using Old English as "devastated wasteland" (OE. ceart "wild public land" and myscan "to ruin"). In this case, such a name fits well, since the area here could indeed be subject to anthropogenic impact during the extraction of copper ore.

Copper mine Kartamish at present

Among other Anglo-Saxon place names in the Donbas, these and be: Borzhikovka, Vergulevka, Golmovsky, Gladosovo, Dyliyevka, Kramatorsk, and Kumshatskoye. We can speak with the most confidence about the origins of the name of the Mius River. Old English offers us the word mēos «moss, swamp», which may be appropriate for the name of the river with a swampy floodplain. This same root is present in the name of the Kalmius River, but it could be named by analogy later because the Anglo-Saxon place names were not found nearby.

At left: The Mius River

The photo of Оlga GOK. Rostov-on-Don.

In Donbas, the Anglo-Saxons came into close contact with the Scythians and took an active role in the life of the North Black Sea region. This is evidenced by explaining some of the realities of the Scythian times recorded by Herodotus and other ancient historians. For example:

Σκυθαι (Scythians), the Greek name of Scythians stands for good using OE. scytta "a shot". The Scythians were the best archers and the Greek ethnonym "Scythian" was considered synonymous with the archer.

ακινακεσ (akinakes), a short iron Scythian sword – OE. ǽces «an ax» and nǽcan «to kill».

σαγαρισ (sagaris), battle-ax, weapon of the Scythians – OE. sacu "war" and earh “arrow”.

The name of large boneless fish αντακαιοι may also have Anglo-Saxon origin. Similarly, a lot of proper names and titles of the peoples of the Scythian and Sarmatian times can be decrypted using Old English or Saxon. All they are summarized in Alan-Anglo-Saxon Onomasticon and some excerpts from it are given below:

Αγαθιρσ (agathirs), Αγαθιρσοι (agatirsoi) – according to Herodotus Agathyrsos was a son of Heracles and gave rise to the tribe of the Agathyrsians – OE đyrs (thyrs) "a giant demon, a magician" is well suited for both the name and the ethnonym. For the first part of the name, we find OE ege "fear, terror", and the whole means "terrible giants or demons". However, OE āga "owner", āgan "to have, take, receive, possess" suit phonetically better. Then the ethnonym can be understood as "having giants". Below, we decipher the ethnonym the Thyssagetai (see Θυσσαγεται) as a nation of giants in the north of Scythia. Thus, we can suppose that the Agathyrsians subdued the Thyssagetai

Αναχαρσισ (Anacharsis), he was known as an alleged Scythian traveler and sage. However, Anacharsis was not a Scythian. It can be concluded from the phrase of Herodotus: "Now the region of the Euxine upon which Dareios was preparing to march has, apart from the Scythian race, the most ignorant nations within it of all lands: for we can neither put forward any nation of those who dwell within the region of Pontus as eminent in ability nor do we know of any man of learning having arisen there, apart from the Scythian nation and Anacharsis". (HERODOTUS, IV, 46 ). Anachars was the son of Gnuros, the son of Lycos, the son of Spargapeithes. All these names can be decrypted using Old English. Then, an Old English match must also be found for the name Anacharsis: Old Saxon. āno "without", OE hors/hyrs "horse" (ie, "Horseless").

Ατεασ (Atheas) was by Strabo a mighty Scythian king, united under his rule all Scythia – according to Abaev "true" (Av haiθya-, Old Pers. hašya-, Os äc-, äcäg-, which phonetically are faulty). Better, according to Holthausen, occurred in names OE æđ, going back to æđele "noble, honourable, glorious" (Holthausen F, 1974, 13)

Βορυσθενεοσ (Boristheneos), the Dnieper River – OE. bearu, Gen. bearwes „forest”, đennan „to expand, extend”.

Γνυροσ (gnuros), the son of Lykos, the father of Anacharsis – as Shaposhnikov asserts, the name has no features as of Indo-Iranian and Eastern-Iranian origin (SHAPOSHNIKOV A.K. 2005, 39), but cf. OE gnyrran "to grind". Akin Germanic words mean "to roar, growl." These senses do not seem suitable for a name, but derived nouns from these verbs could be the name of a beast. Ukrainian, Belorussian, Russian, Polish words knur, knur mean "a male pig". Moreover, in the same languages, as well as in Slovak and Lusatian, there are words close to the Greek form of the word (Ukr., Rus. knoroz, Blr. knorez, Slk. kurnaz, Pol. kiernoz, Up.-Lus. kundroz – all "male pig"). In the etymological dictionaries of the Ukrainian and Russian languages, explanations of the origin of all these words are considered unsatisfactory, not quite clear, or onomatopoeic (A. VASMER MAX. 1967: 264-265 and A. MELNYCHUK O.S., Ed. 1985: 474) as a corresponding root is absent in the Slavic languages. It can be assumed that in Old English there was the word *gnyr "boar, wild boar". It was borrowed in this sense by the Slavs. Thus, the name of the king's grandson could mean "wild boar". Cf. Θυσκεσ. How the Slavic languages have got also the Greek form of the word, it is necessary to find out, because such a word is absent in the Greek language. Perhaps, in the language of the Greeks who inhabited Ukraine in Scythian times, it existed, being borrowed from the neighboring Anglo-Saxons.

Θυσσαγεται , the Thyssagetai, one of the folks in Northern Scythia mentioned by Herodotus, or Thyrsagetae (by Valery Flaccus) – V.I. Abayev explains this name as "fast deer" (Pers, Kurd. tūr "rabid"), Os sag "a deer". The presence of the morpheme getai/ketai (Μασσαγεται, Ματυκεται, Μυργεται) in the names of several tribes is noteworthy. In addition, the Thracian tribes Getae (Γεαται) are known in history. We can suppose that this word means "people". The closest to it is the Chuv kĕtỹ "a flock, herd". Then Thyssagetai were "unruly people" (OE đyssa "rowdy”). If the form of Valery Flaccus is more correct, it is likely since it echoes the name of the Agathyrsians. (see Αγαθιρσ, Αγαθιρσοι), then the Thyrsagetae means "the people of giants and wizards" (O. Eng đyrs "a giant, demon, wizard").

Ιδανθιρσοσ (Idantirsos), Scythian king – OE eadan "performed, satisfied” and đyrs "a giant, demon, wizard".

Τιαραντοσ (tiarantos), an unknown small river in Scythia – nothing better than OE tear "tears, drops" and andian "to envy, jealousy".

Having occupied an area rich in deposits of copper ore, the Anglo-Saxons received an economic advantage overpopulation of the Pontic region and, consequently, political domination. Over time, they stood at the head of the mingled Alans Union (for details see the Section Alans – Angles – Saxons).

During the Great Migration, this part of the Anglo-Saxons, known in history as the Alans, with other Germanic tribes set off on a long trek through Europe and after a short time, they found themselves in Spain. These events are described in detail by contemporarys, however, the mass movement of the Anglo-Saxons had not been observed by historians since it was not so dramatic and stretched on for several centuries.

Restoring the prehistory of the Anglo-Saxons in a wide area of Eastern Europe, it should be noted that most of them were not directly related to the Alans. While the Alans, who settled on the Northern Black Sea coast and remained there until the arrival of the Huns, the Angles and Saxons moved their way towards Germany, and from there they already reached the British Isles. The study of Anglo-Saxon place names in Central and Eastern Europe helps to restore the picture. As always in the case of mass migration, part of the migrants remain at their place of temporary residence. The rest of the tribesmen set out again after some time (a year or two or more). A chain of settlements, whose names often survived to this day, arises along the way.

We find one such chain in Western Ukraine, and it has the highest density of place names in Old English toponymy in continental Europe. It runs from the city of Halych to the city of Kalush and farther through the Kalush district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region in this order:

Halych (Galych), a city – OE gāl "joyful, cheerful", eace "multiply, increase"

Krylos, a village of the Ivano-Frankivsk district – OE griellan "to anger", ōs is the name of a pagan god"

Viktoriv, a village in Ivano-Frankivsk district, Ivano-Frankivsk Region – OE wīċ "dwelling, settlement", Þūr/Þōr "God of Thunderer"

Bryn', a village in Ivano-Frankivsk district, – OE bryne "fire".

Vistova, a village in Ivano-Frankivsk district – OE wist "food", "maintenance".

Khotyn', one of the areas of low-rise estate development in Kalush – OE heah "high", hoh "headland", tūn "settlement, village”.

Sivka, a village in Kalush district – OE seaw "juice".

Tuzhyliv, a village in Kalush district – OE tulge "firm", "strong".

Svarychiv, a village in Kalush district – OE swār "heavy".

Low Strutyn, a village in Kalush district – OE strūtian "become stiff".

Upper Strutyn, a village in Kalush distric – OE strūtian "become stiff".

Lopianka, a village in Kalush district – OE loppe "spider".

Ilemnia, a village in Kalush district – OE ill "callus", emn/efn from efnian "smooth", "even".

Angelivka, a village in Kalush district– OE angel "angle, hook".

Lolyn, a village in Kalush district – OE lǣl "rod", "scourge".

Veldizh, (Wełdzirz), an old name of the village of Shevchenkove in Kalush district – OE weald 1."forest", 2. "might", "rule".

Patsikiv, a village in Kalush district – OE pæcan "deceive", eaca "growth", "increase".

Hoshiv, a village in Kalush district – OE husk "mockery".

Gerynia, a village in Kalush district – OE gernan "demand, desire".

Svicha, a river, rt of the Dnister – OE swiće "end".

A dense chain of placenames in Galicia may indicate the existence of a trade route along which Anglo-Saxons established their settlements (see map below). The existing salt reserves in the Precarpathian region suggest that salt was the main commodity along this route. By controlling the salt trade, the Anglo-Saxons established their own quasi-state, which, although not mentioned in historical documents, can be inferred from the White Croatia described by Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

A dense chain of placenames in Galicia.

The presence of Anglo-Saxons in Galicia in ancient times is also confirmed by the occurrence of Old English surnames among residents of the Kalush district, where the trade route, or in the next districts. Surnames of Old English origin are not uncommon in Ukraine, but in this case, the more compelling arguments are those that are predominantly common in this and the next districts. For example, these include:

Ficalovych, all the bearers of this surname live in Ivano-Frankivsk or in the next districts of Lviv Region – OE ficol "cunningly".

Trambolak, of the eleven bearers of this surname, nine live in Kalush – OE trem "small thing", būl(a) "adornment, decoration".

Izdryk, of the thirteen bearers of this surname, seven live in Kalush – OE easter from east "east".

Hoshylyk, 56 bearers across Ukraine, almost all in the Kalush district – OE husc "mockery".

Burnych, 599 bearers across Ukraine, with the largest number in Kalush and the Kalush district – OE burn "child".

Shymkiv, 1099 bearers across Ukraine, with the largest number in Kalush and the Kalush district – OE sćīma "beam, light".

Khomyn, 3286 bearers across Ukraine, with the largest number in Kalush and the Kalush district – OE hām, home "home".

It's safe to assume that the Anglo-Saxons left traces of their presence in Galicia beyond just onomastics. Their presence should be sought in villages marking trade routes, where other surnames of Anglo-Saxon origin can also be found.

There are many such chains of placenames in continental Europe, mostly local in nature, but two of them reflect the two main migrations of Anglo-Saxons into Western Europe. One that crosses central Poland, and the second that runs along the Carpathian Mountains and through the Moravian Gate to Bohemia. Obviously, the Angles moved through central Poland and then through northern Germany. The Saxons came into Bohemia and, through the valley of the Elbe River, entered Germany, where the states of Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt are now. Here, most of them stayed permanently. The other part has moved on to the North Sea coast, which is now the state of Lower Saxony.

One of the evidence of movement of the Anglo-Saxons through Poland, the name of the village Czorsztyn in Lesser Poland Voivodeship was decoded as "jutting rock" (OE. scorian "to jut out", stān "stone, rock"). Really, there is in this village a steep rock on the shore of the reservoir formed by the Dunajec River (see. photo at the right). Similar words are or were present in German (OHG scorra "rock", Ger. Stein "stone"). In addition, there are in Poland several settlements that contain the component sztyn (Wolsztyn, Falshtyn and possibly others), all they can have as German (Teutonic) as the Anglo-Saxon origin. The Anglo-Saxon origin may be assumed more justified only if they are part of a chain or cluster of names as can be seen in the case with Czorstyn. However many place names in the band passing through Central Poland have a clear Anglo-Saxon origin. For example, the name of the village of Kornaty can be interpreted using OE. corn "grain", ate "oats". Another fact is more interesting. There are in the band ten settlements called Konotop and four called Konotopy. These names have Slavic appearances, but the fact that they are so numerous with questionable Slavic interpretation and that they form a strip caused assuming their non-Slavic origin. Only the Anglo-Saxon origin could such opportunity be provided. The movement of the Saxons through Czech Republic is marked by place names such as the Olomouc, Chrudim and several others, including the component tyn corresponding OE tūn "village". Interpretation of other place names can be found in The Complete List of Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe

Anglo-Saxon place names in Eastern Europe

On the map, most of the dwelling sites of Anglo-Saxon origin are marked with dark red points. The settlements of Markovo, Markino, and similar have purple color. Hydronyms are marked in blue.

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons is colored red, blue is the territory of the Sosnica culture, the green is the territory of the Rostov-Suzdal principality. Sarmatia is marked in yellow.

Nevertheless, many Anglo-Saxons remained in Eastern Europe, and this fact has historical evidence. In 970 the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces (969 -976) sent via ambassadors a message to the Kyiv prince Svyatoslav (964 – 972), where:

For I think you are well aware of the mistake of your father Igor who, making light of the sworn treaties, sailed against the imperial city with a large force and thousands of light boats but returned to the Cimmerian Bosporos with scarcely ten boats, himself the messenger of the disaster that had befallen him. I will pass over the wretched fate that befell him later, on his campaign against the Germans, when he was captured by them, tied to tree trunks, and torn into two (LEO the DEACON. 1988, VI: 10).

Here we mean Prince Igor, martyred by the hands of the Slavic tribe Drevlians inhabiting the Anglo-Saxon area at that time. In this regard, the origin of the ethnonym "Drevlians" can be from the name of a well-known Germanic tribe Turvin (YAYLENKO V.P., 1990: 116), but I think that the tribe got its name after the murder of Igor from OE. dreawian “to punish”. A derivative of it dreawl “punisher” could exist, since there was an OE dræwel as part of a word meaning "hot iron".

The Drevlian tribe didn't belong to the ancient Rus’ state for a long time. They were included in it at least in the 10th century, as it was repeatedly stressed (NASONOV A.N., 1951: 29, 41, 55-56). The fact that the Vikings could not include the adjacent to the Polans Drevlyans into the "Russian land" can say that they were the remains of the Anglo-Saxons mixed with the alien Slavic population. We find a similar picture in Volhynia, inhabited by the Slavic tribe of Dulebs (Dudlebs). According to some scholars, this ethnonym is derived from W.-Gmc Deudo- and laifs (A. VASMER MAX. 1964: 551 and A. MELNYCHUK O.S., Ed. 1985: 144), that is, it can be translated as "the remaining Teutons", since the first part of the word means "Teutons" (actual Deutsche "German"), and the second – "rest of" (Goth. laiba, OE. lаf). However, it is believed that Leo the Deacon made a mistake by writing Germanoi instead of Derewianoi, that is, the Derevlian. The possibility of such an error must be borne in mind.

In this regard, one can suggest that the legendary Kievan princes Askold and Dir were also Anglo-Saxons. The names of the princes have no convincing decryption, therefore we can consider their Anglo-Saxon origin. Especially, Dir's name can be deciphered well – OE dieren "to value, praise", diere "expensive, valuable, noble". Askold's name can be deciphered as "elected prince": OE āscian "to ask", to call, choose, elect" and eald "old", ealdor "prince, lord". However, there is another interpretation of this name as "gray-headed", that is, a wolf warrior, but without indicating which language (YAKOVENKO N.M. 2005: 37).After the murder of Askold by Oleg a certain Olma set up the church of St. Nicholas at his grave. Perhaps he was a relative of Askold because his name could also be Anglo-Saxon: OE. ulm "elm". Since we recognized that the top of the Khazar Khaganate was made up of the Anglo-Saxons and where the usual form of government was a duumvirate (see Khazars), it can be assumed that at that time Kyiv was a part of the Khaganate. There are historical documents showing that the Jewish-Khazar community was not only present in Kyiv but also laid the foundations for the statehood of the future Kyiv Rus (GOLB N., PRITSAK O., 1997, 159). The Anglo-Saxons, who already had a good experience of forming the state of Khazaria, were to play a leading role in this process.

Askold's grave in Kyiv

As shown by the analysis of Anglo-Saxon toponymy in Eastern Europe, the Anglo-Saxons settled on a vast expanse from the banks of the Dnieper to the Volga in the east and to the city of Veliky Novgorod in the north, which can be associated with the city of Novietun, mentioned by the Jordan (see. section Slavs: Territory, Dialectal Split). In this case, Lake Mursiano can not be anything other than Lake Ilmen on which bank the Veliky Novgorod is located. The name of the lake has Anglo-Saxon origin – OE murcian "to complain, care".

The highest density of Anglo-Saxon toponyms is observed on the territory of the former Vladimir-Suzdal principality. From time immemorial, these places were inhabited by Finno-Ugric tribes, and at the end of the first millennium AD Slavs advanced here too, and a hundred years later the Rostov-Suzdal principality suddenly emerged here, which quickly seized the leadership from Kyiv. Even Russian historians are amazed at this. In particular, V.O. Klyuchevsky wrote that there is no clear answer to the question of where the new Upper Volga Rus grew up (KLUCHEVSKIY V.O. 1956: 272). Agreeing that the Anglo-Saxons founded most ancient towns of this region, it must be assumed that just they were who laid the foundations of statehood here, uniting under their domination disparate native tribes. However, during the heyday of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, the Anglo-Saxons were already fully assimilated by a larger local population (in detail see Anglo-Saxons at Sources of Russian Power).

The fact that the Anglo-Saxons stayed in their ancestral home before the arrival of the Slavs here is confirmed by some English-Slavic lexical matches:

Eng. cheek – Ukr. shchoka, Rus. shchtka, Blr. shchaka Pol. szczęka all "cheek".

Eng. child – ORus. chelad', Bulg. chelad, Cz. čeled "family, servants" and other Slavic.

OE gnyrran "to crunch, croak", Eng. grunt – Rus., Ukr. knur, Blr. knyr "male pig", Pol. knur "boar", Cz. knourati "to whine" and other similar Slavic words.

OE scand "shame, disgrace", rāp "rope" – Rus. shantrapa "rabble, scoundrels", that is, people worthy of hanging.

Eng. scatter is semantically close to "to spread out" and in this sense can be considered a connection of this word with Rus., Ukr. skatert' "table-clouth". Both words have no reliable etymology. The Chuvash language has the word šatra "rash", "uneven, rough surface." Just its previous form was borrowed by the Anglo-Saxons from the Bulgars. They had no the sound š, so they articulated it as sk. Borrowed from the Anglo-Saxons word was used as skatert' for tablecloth.

Eng. scant – Rus., Ukr. skudnyi, Bulg. oskuden "scarce" a.o. Maybe here also Osset/ qyndy "scanty".

Eng. strum – Cz., Pol., Rus., Slv., Ukr. struna "to strum" a.o.

OE. *witing from witian "to order", "to determine" – Rus., Ukr. vit'az', Bulg. vitez, Slvk. vít'az и др. слав. It is believed that Slav. *vítędzĭ was borrowed resulting dissimilation from the Gmc. *viking (VASMER M. 1964" 323). However, such examples are rare, and the narrowly specific meaning of “pirate” did not correspond to Slavic realities.

Eng. wolf – Rus. volkhv, Bulg. vlъkhva "a wizard", Sloven. volhva "a soothsayer".

Anglo-Saxon origin can be expected for Ukr., Rus. ataman, (Ukr also otaman, Old Rus. vatamanъ), which etymology is controversial among linguists. If the initial consonant in the word vatamanъ is assumed to be prothetic, then OE *atta (PN Atta, OHG atto) "father" and OE. mann "man, hero" phonetically and semantically suits well.

Among the similarities between English and Ossetian languages, which were discussed in the section " Germanic tribes in Eastern Europe in the Bronze Age", could be those which relate to the time when the Anglo-Saxons and the Ossetians were in the steppes of Ukraine. Highlighting them is difficult, but they can be considered separate Anglo-Saxon-Ossetian matches or those with no reliable Germanic etymology. For example:

OE. corđor "group, herd, multiplicity" – Osset. qord, "the same".

OE. ealuđ "beer" – Osset. äluton "beer".

OE. lođđere "a beggar" – Osset. lädär "good-for-nothing".