Relationships of Languages and Migration of Their Speakers: A Compendium of Research.

The main subject of study of prehistoric ethnogenetic processes is the relationship of languages belonging to the same family and the spatial arrangement of the places of formation of those proto-languages from which they originate. It would be impossible to avoid errors when dealing with such a wide variety of materials drawn from old times and places, races, and languages. The currently available large body of knowledge about the subject of research is an unsystematic set of facts, the arbitrary use of which by the method of deduction gives different results. Adventuring to interpret Kant, I made the method of cognition the starting point of my research. Firstly, the available data on the vocabulary of the languages being studied are brought into a certain system and on their basis, using the graphic-analytical method, a graphic diagram (model) of their family ties is constructed, and then a correspondence is found for it on a geographical map and the places of formation of individual languages are determined. It is a new and personal work, I would venture to say without doubt, containing, whatever its value, a fresh and original analysis of the subject. This method allows us to clarify or even revise some ideas and reconsider the achievements of historical linguistics. However, it would be a big mistake to consider my work in any sense as setting the direction in the study of ethnogenetic processes. Even though I practice an interdisciplinary approach in my work and use scientific results from other fields of knowledge, I do not take into account that ethnogenetic processes are studied by sociologists and, independently, also by paleogenetics. The fact is that the formation of ethnic communities contains two completely different processes – migrations of language or gene speakers, in which social development can also occur.

The graphic-analytical method was first used for the determination of habitats of ancient Slavs (STETSYUK V.M. 1987), and, in the next years, about thirteen dozen different languages were examined similarly. The total amount of vocabulary used for the construction of graphical models is about 135,000 words (see Table 1). About half of the data that I collected from etymological and bilingual dictionaries and used at the very beginning of the research is presented as Etymological Dictionaries-Tables. After appearing on the Internet, data from the project The Tower of Babel was used. In addition to graphic-analytical studies, searches for lexical correspondences between the languages of different groups and families were carried out, and the results of studies using the inductive method were linked with data from archeology, onomastics, mythology, and ethnography.

Table 1. Quantitative data about vocabulary taken to the study.

| Families and groups of languages | Number of languages | Number of isoglosses | General amount of words |

| Sino-Tibetan | 7 | 2.775 | 9.700 |

| Tungus | 11 | 2.234 | 10.200 |

| Mongolic | 8 | 2.250 | 8.500 |

| Nostratic | 6 | 433 | 2.600 |

| Abkhaz-Adyghe | 5 | 1.800 | 4.500 |

| Nakh-Dagestan | 27 | 1.900 | 24.000 |

| Indo-European | 14 | 2.554 | 12.381 |

| Finno-Ugric | 12 | 1.913 | 9.584 |

| Turkic | 13 | 2.558 | 19.670 |

| Germanic | 6 | 2.630 | 11.065 |

| Iranian | 11 | 1.773 | 8.249 |

| Slavic | 10 | 3.200 | 12.000 |

| Total | 130 | ≈ 26.000 | ≈ 135.000 |

Below is a more detailed description of the use of the graph-analytical method. The idea of the graphic-analytical method consists of the geometrical interpretation of interrelations between cognate languages based on quantitative estimation of mutual linguistic units in pairs of languages within one language family or group. The larger kinship of languages is usually connected with the greater amount of mutual linguistic units, and these are just mutual words that are most suitable for statistical processing. This method is based on the supposition that inverse proportionality exists between the number of mutual words in a pair of languages and the distance between natural habitats where these languages were formed. To put it simply, the closer to each other the carriers of two cognate languages lived, the greater the number of mutual words they had in their languages. It is clear that only old words are to be regarded that a person could use in prehistoric times, but not those which arose later at higher levels of civilization development. It is not easy to determine the old words, though. There are various methods for this purpose.

Hence, having chosen the needed words from all the languages of the family under research, we proceed to estimate. At first, a common lexical stock should be defined, which is one of the characteristics of the linguistic community, but does not reveal any information about the level of kinship between different languages and, therefore, should be excluded from the calculation. The rest of the words can be common to two or more languages, but we count the number of mutual words in pairs regardless of whether they exist in other languages or not. After such a calculation in all possible pairs of languages, the graphic model of their kinship is constructed. The graph reflects the location of areas where each of the languages was spread on the common territory of the whole language family. Each area corresponds to a tight accumulation of knots on the graph. This accumulation is formed by the ends of ribs (segments) with a length inversely proportional to the number of mutual words in the pair of languages. The number of ribs is equal to the number of pairs of languages, and the number of knots is one unit less than the number of languages. The process of graph construction is simple and only needs some elementary knowledge of geometry.

As a next step, we have to find a suitable place for the received graph. The suitable territory should consist of areas with more or less distinct natural boundary lines, such as rivers or mountain ranges. Natural barriers complicate contact between the people in the areas and, accordingly, prevent them from exchanging newly arisen words that result in the split of a primary language. The more distance between areas, the larger of differences that arise in the languages of their inhabitants. There are very few places on the earth’s surface with the accumulation of natural areas, which we will name ethno-producing areas, therefore, searching for them is not complicated. A lot of people think that any kind of graphical model can be placed in any kind of place, but this is a fallacy. The same as the two nets, formed of triangles and squares, cannot be superposed, it is similarly impossible to superpose a graphic model upon an incongruous place on a map. Thus, the fact of correctly placing the graph on a map is meaningful in itself.

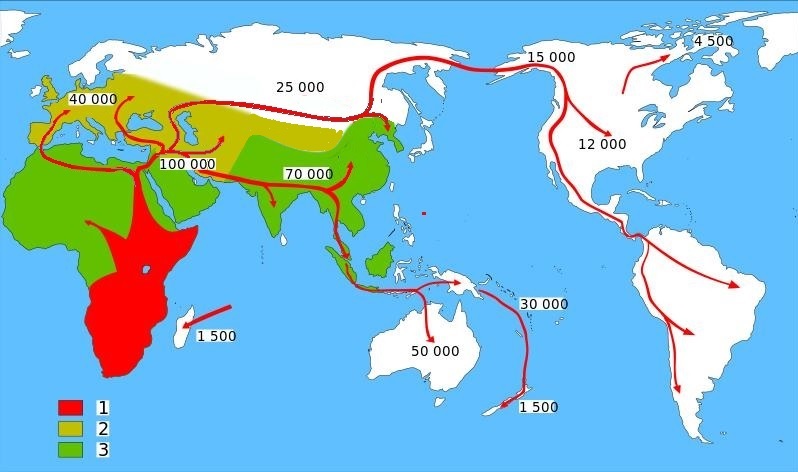

Left: The Peopling of Eurasia by Homo Sapiens.

1. Homo sapiens.

2. Neanderthals.

3. Early Hominids.

Modern humans began peopling Eurasia from Asia Minor. The first came here people of Mongoloid race, the most active part of which moved further around the Caspian Sea and eventually reached Siberia and the Far East. Some of the group moved to America through the Bering Strait later. The bulk of them populated the Amur River basin and surrounding areas. There, the Tungus-Manchu and Mongolian languages were formed (see Map below). This process is described in detail in the article "Far East: The Relationship of the Altaic and Turkic Languages.".

See The Mongolic and Tungus languages in a larger map

On the map red signs marked areas of the formation of the Mongolian languages, yellow – Tungus (click on the icons to find out what kind of language is formed in the designated habitat)

A large group of Mongoloids stayed in the Near East and the Caucasus, populating suitable life valleys. There, the Sino-Tibetan languages were formed (see Map below). They can be associated with Upper Paleolithic culture, which was common in these places (40-30 thousand years ago). This process is described in detail in the article "The Formation of the Sino-Tibetan Languages and their Speakers Migration".

The map shows the areas of the formation of the Tibetan, Burman, Kachin, Chinese, Kiranti, Lepcha, and Lushey languages.

Meanwhile, a race of Caucasians was formed in North Africa, whose representatives began to settle in Europe via Anatolia and the Balkans. Obviously, at the beginning of the Mesolithic, they appear in the Near East and displace people out of the Mongoloid race into Central Asia. Newcomers have a common language, which eventually split into six separate in the same habitats, where Sino-Tibetan was formed. These languages are called Nostratic and include Indo-European, Uralic, Afro-Asiatic, Dravidian, Kartvelian, and Turkic.

Integrated graphic models of these six languages of the Nostratic superfamily allow you to define areas of their formation in Asia Minor and the Caucasus and around the three lakes nearby – Van, Urmia, and Sevan (see. Map above). There is at the center of this area the biblical Mount Ararat. The map shows the area as a hypothetical form of the previous North Caucasus language (arrows indicate the path of migration of carriers of the later Abkhaz-Adyghe and Northeast Caucasian languages).

Obviously, at the end of the 6th mill. BC. a bulk of Nostratic language speakers to populate new territories. In the old ancestral home remained Kartvelians (ancestors of modern Georgians), and perhaps a small group of other ethnic groups remained. Semitic-Hamitic and Dravidians moved to the south and the speakers of the Indo-European, Uralic, and Turkic proto-languages alternately moved through the Derbent passage to the North Caucasus, and then gradually spread across the East European Plain, assimilated among the indigenous population, which, however, adopted more perfect alien language.

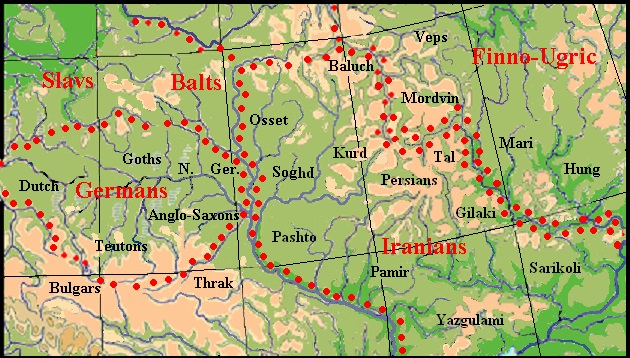

Graphical models for the language of each of these three families allow us to find the territory of the settlements of their speakers and form areas of next-level languages. The whole territory of Eastern Europe from the Vistula to the Ural is divided by a river network into several tens of ethno-producing areas quite clearly. Indo-Europeans settled in the basin of the middle and upper Dnieper, and here in areas formed by its tributaries and tributaries of the Pripyat and Desna Rivers Indo-European dialects were formed, of which eventually evolved these languages: Greek, Italic, Germanic, Slavic, Baltic, Tocharian, Celtic, Illyrian, Thracian, Phrygian, Armenian, Iranian, and Indoaryan. Most of the speakers of the Uralic proto-language was not reached the Ural and settled in the Volga basin. Such primary Finno-Ugric languages: Finnish, Estonian, Vepsian, Sami, Mordovian, Mari, Hungarian, Udmurt, Komi, Khanty, Mansi, and another two or three languages, which later disappeared, were formed in the space of the right-bank part of the Volga. That part of the Uralian, which has moved beyond the Volga to the north, had already no close contact with its old relatives, so their language developed independently and has given rise to the languages, which are now known as the Samoyed. Ancient Turks occupied the territory between the lower Dnieper and Don Riber, here Turkic language was also differentiated.

At the beginning of the III millennium BC. the majority of Turkic tribes began to leave their ancestral home, gradually populating the large territory from the Carpathians to the Altai. Those tribes of Turks (mainly Proto-Bulgarians), who crossed to the right bank of the Dnieper, assimilated Trypillians, began to colonize vast areas of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe, extending the Corded Ware culture (see the map below).

The Bulgars left traces of their migration in numerous place names (about 600 units), which were decrypted using the Chuvash language (see Google map below).

On the map, the territory of the Globular Amphora culture is tinted with light green color.

The icons in the form of purple dots indicate the settlements with the names of Bulgarian origin, which may correspond to the times of CWC or close to them. Maroon ones are of the latter, of the Scythian period.

Asterisks mark known single or group sites of CWC. The orange line indicates the western border of the Trypilla culture, and the yellow dots indicate the possible place names of Trypilla times. Browns show the area of Indo-Europeans, and green is the territory of the spread of Fatyanovo and Balanovo cultures.

The blue line indicates the border of the settlement of the Finno-Ugric peoples.

Azure circles mark Bulgarish names of rivers and lakes.

Yellow space – Trypillian culture. Its most western sites are marked by orange asterisks.

Brown space – the territory of the Indo-Europeans. Green space – Fatyanovo and Balanovo culture

Many lexical parallels between the Chuvash and German (see. the section Chuvash-Germanic Language Connections) can be explained by two reasons. The Urheimat of the ancestors of the Germans, which we call the Teutons, was in the Volyn Region of Ukraine, and Bulgars populated the neighboring territory of Galicia. Thus they could be a mutual linguistic influence. When the Teutons in the process of migration reached Central Europe, they settled among the Bulgars, who were there from the time of the Corded Ware culture, gradually assimilated them but borrowed some Bulgarish words.

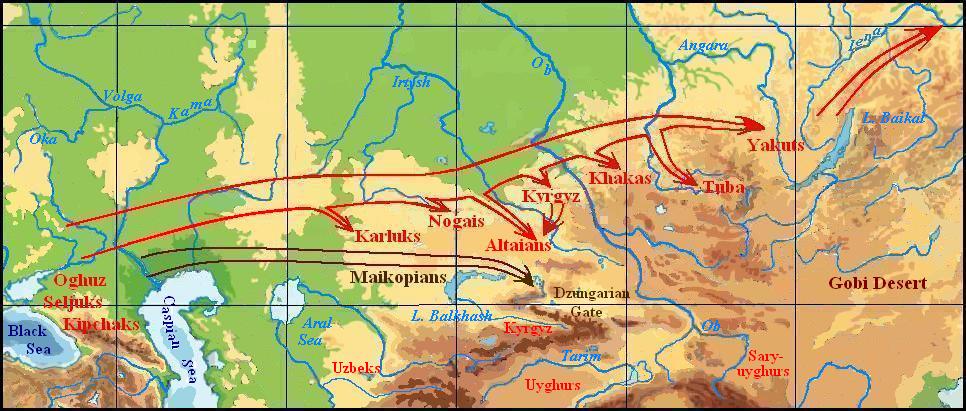

Simultaneously with the movement of the Bulgars to Central Europe other Turkic tribes populated the Northern Caucasus and migrate across the Volga River. They, passing Kazakhstan and keeping order, due to the location of the primary areas of settlements, moved to Central Asia, Siberia, and the Altai (see. Map below).

Those Turkic tribes, who came to the Altai, got contact with the native speakers of the Mongolic and Tungus languages. The richer and more developed Turkic languages have a big impact on aboriginal languages, which were largely engaged at hunting and gathering, that were standing still at a fairly low level of development. As a consequence, the Mongolic and Tungus languages, as well as genetically related to the Japanese and Korean, have a certain number of common features with the Turkic. This gives reason to unite them all into one so-called Altai language family, although the Turkic languages, as we have seen, genetically do not belong to it.

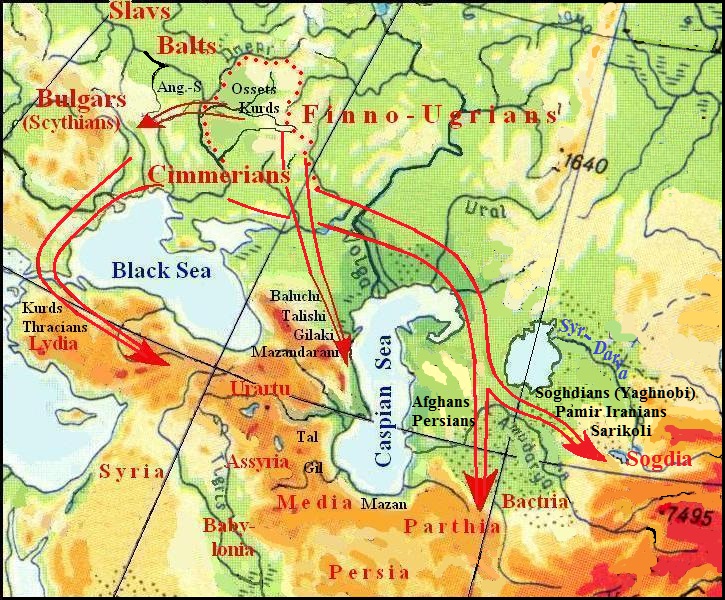

After the majority of Turks have left their lands between the Dnieper and Don Rivers, the movement of the Indo-European tribes began too. The Illyrians and Greeks moved to the Balkans, and the Italics (the ancestors of the Falisci, Osci, Umbri, Sabines, Latins, and others) after long wandering finally settled in the Apennine peninsula. The second wave to the Balkans consisted of the Phrygians, Ancient Armenians, and Thracians (ancestors of the Albanians). The Indo-Aryans together with the Tocharians reached Central Asia and then advanced to the Hindustan. The Slavs having their Urheimat on the very north of the Indo-European space moved to the west, but stopped at the banks of the Vistula River, while their southern neighbors, the Celts went further in Central Europe. It should be noted that the population leaves their homes never completely, but the remaining part is subjected to assimilation by more numerous newcomers, although the language of the indigenous population leaves traces of its influence on their tongues. Such influence of language substrate on ethno-producing areas significantly accelerates the process of differentiation of a common language of newcomers. Therefore, when the Germanic people, Balts, and Iranians took habitats left by other Indo-Europeans, they were mixed with the previous population. The Germanic people occupied areas of the Celts, Illyrians, Greeks, Italians, and their common Germanic language was quite soon divided into five dialects from which later evolved Gothic, modern English, German, Dutch, Frisian, and North Germanic languages (Swedish, Norwegian, Danish). At the same time, there was a process of differentiation of Iranian and Baltic languages. Migrations of the Indo-European tribes are shown in the map below.

The tribes of the Balts, Germans, Iranians, and Thracians stayed near their Urjeimat, they occupied empty areas. Sometimes the Armenians and Phrygians are still present in left-bank Ukraine (see the map below).

In the middle of the first mill. BC. most of the Iranian tribes migrate in turn to Central Asia. In Eastern Europe, stayed the ancestors of Baluchis, Kurds, Ossetians, Gilaki, Talysh, and possibly Mazanderani people. The Kurds passing to the right bank of the Dnieper River, settled Podolia. Later, one portion of them moved to Central Europe, where they became known in historic times as Cimbri. The second part has moved to the steppes of Ukraine. Ossetians stayed in the upper reaches of the Don till the Scythian times.

General picture of the Iranian migration in Minor and Central Asia

The rest of the Iranian tribes who lived in Eastern Europe, became known under the name of Cimmerians. They were joined by those Kurds who migrated into the steppes. The historically accurate times Cimmerians inhabited the Azov and the Black Sea steppes and left traces of their stay in the archaeological sites, which are united into a Cimmerian culture. Over time, they were driven out by the Scythians in Asia Minor.

The Scythians were ancient Bulgars who, for two millennia stayed in Galicia, where they became the creators of Komarovo and Vysotsk cultures. At the beginning of the first millennium BC., they began moving in different directions. Most of them moved to the east, reached the Dnieper River, and along the Vorskla River switched to Left-Bank Ukraine. They can be connected with Chernolis culture which has developed as a synthesis of Vysotska and Bielogrudov ones. Of all For-Scythian cultures, it was the most common in Ukraine (see the map below).

Archaeological Cultures of For-Scythian Time in the Ukraine

І. Cimmerian sites

ІІ. Vysotska culture

ІІІ. Holihrady group

ІV. Moldovian group

V. Chornolis culture

(More detailed see inthe section Genesis of Scythian Culture}

Thus, the Scythians did not come from the east, as is commonly believed, but from the west. Archaeology and linguistics confirm this idea.

Most of the Scythian names, which have remained in historical sources (and there are about 200), can be well deciphered by means of the Chuvash language, but among them, there are several such names, which doesn't have Chuvash matches. They can be decrypted by means of the Kurdish language. Germanic tribes migrated from their ancestral homeland mainly west- and northward, but the ancient Anglo-Saxons remained in Ukraine for a long time, and their tracks were also kept in numerous place names (about 170 items). Thus, during the time of Herodotus, the Anglo-Saxons were among the peoples of Scythia (see the map below)

On the map, the toponyms of Bulgarish origin are marked with a burgundy color, the azure names are of Anglo-Saxon, red – Kurdish, purple – Mordovian, green – Ossetian, dark green – Chechen, orange – Hungarian, black – Greek. The red line marks the border of Scythia of Herodotus.

The violet rhomb denotes the hillfort of Belsky near the village of Kuzemin, which some scientists associate with the ancient city of Gelon.

The red rhomb denotes a Scythian fortification near the village of Chotyniec in Poland.

More toponymic studies are discussed in section "Prehistoric Place Names of the Central-Eastern Europe.".

Finno-Ugric tribes remained outside of the ways of great migrations, but gradually moved northward in the order, which was determined by the location of their habitats in the ancestral home. For example, the Sami (Lapps), who held the extreme northern area of total Finno-Ugric territory, was the first in the movement to the north and are now the most northern Finno-Ugric ethnic group. As the ancestors of the Mansi had their ancestral home in the far north-east and now the Mansi occupy the same position in the whole modern-day Finno-Ugric space.

Approximately the same can be said of other Finno-Ugric peoples, with the exception of the Hungarians. Their homeland between the rivers Hopper and Bear lying near the tracks of the great migrations, so their historical fate brought them to Central Europe. Since the rest of the Finno-Ugric peoples were not going to the distant stranger, no none of them had a possibility to occupy a large empty area, so the Finno-Ugric languages were not as widely different as the Indo-European ones. Some languages have retained their integrity, while others are divided only into a small number of close dialects or languages.

And finally, the Slavs. The Slavs, who for a long time dwelled in a fairly compact area, also a long time kept the unity of their language. And even after the differentiation, the Slavic languages are more similar to each other than, say, Germanic, which differentiated much earlier.

Map 12. Settlements of Slavic tribes, in the end, I mill. BC – at the beginning of I mill. AD.

Bodr – the Bodriches, Bulg – the ancestors of modern-day Bulgars, Br – the ancestors of Belorussians, Cz – the ancestors Czeches, Lus – the ancestors of the Lusatian Slavs, Lut – the Lutiches, NR – the ancestors of speakers of the northern Russian dialect, P – the ancestors of Poles, Pom – the Pomorian Slavs, SR – the ancestors of speakers of the southern Russian dialect, Slv – the ancestors of Slovenes, Slvk – the ancestors of Slovaks, S/H – the ancestors of the Serbs and Horvats, U/Т – the ancestors of the Uliches and Tivers (?), Ukr – the ancestors of Ukrainians.

The division of the Slavic languages occurred at the beginning of the new era when the Slavs settled the whole former Indo-European territory. For the most part, they are layered on the aboriginals of Baltic origin who changed here the Germanic and Iranian people have already had their own separate languages. Different substrates very accelerated the division of Slavic languages, so the age of each of them has now about eighteen centuries.

In this short presentation many details are omitted, which themselves do not seem significant, but fit well into the overall picture served here, adding to its completeness and reliability. In general, we can say that empirically constructed models of language cognations correspond to geomorphological features of the earth's surface and are confirmed by linguistic and extralinguistic facts. Thus, in this case, G. Vico's philosophical doctrine verum et factum covertuntur (the true and made matching) has its ocular reflection.