Germanic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age

There was the book "The Early Germans and their neighbors: Linguistics, Archaeology, Genetics" (KUZ'MENKO Yu.K. 2011) in Russia, in which the author considers seven hypotheses about the appearance in the historical scene of the Germanic people. The possibility of their ancestral home in Eastern Europe is not taken into account, despite the fact that it has already been considered for 20 years before (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998.) While academic science continues to mill the wind, we return to this issue again.

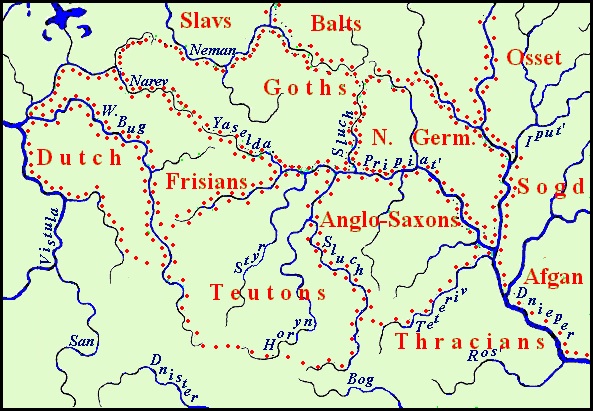

The Urheimat (ancestral home) of the Germanic peoples on the whole Indo-European space, which was determined using the graphic-analytical method, was located in the area between the Neman, Narev, Yaselda Rivers, and its eastern boundary was the Sluch River, the left tributary (lt) of the Pripyat River (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. The habitats of the ancient Indo-Europeans

After First Great Migration when most Indo-European tribes began the migration to new habitats, the Ancient Germanic people still remained near their Urheimat though considerably expanded their settlement territory. This has resulted in the dialectal splitting of their paternal language.

It is generally accepted that the pre-Germanic language was first divided into three branches: eastern, northern, and western [MEIER-BRÜGGER MICHAEL, 2003: 36]. More than a dozen known Germanic languages as a continuation of these original branches are usually divided as follows: the northern group consists of the Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese languages, English, German, Dutch, and Frisian belong to the Western group, and Gothic, the languages spoken by the Burgundians, Vandals, Gepids, and Ruguans are considered as the Eastern languages. However, in accordance with the five Germanic ethnic groups, to which, from the last century, the Vandili, Ingaevones, Istvaeones, Hermiones, and Bastarnae were classified, the Germanic languages can be divided into five groups [ZHLUKTENKO Y.O., YAVORSKA T.A., 1974: 9]. It was later suggested a slightly different division of the Germanic tribes. According to Friedrich Maurer (1898-1984) and other linguists, the Germanic people were initially separated into five tribal groups: the Norsemen (ancestries of the modern Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, Icelanders); the Eastern Germanic peoples (Goths, Vandals, etc); the Elbe Germanic tribes (forebears of the modern Germans, i.e. Semnons, Suebs, Quads, Markomans, Hermundurs, Longobards, etc); the Rhine-Weser Germanic peoples (ancestors of modern Dutch and Flemish people); the North Sea Germanic peoples (the Anglo-Saxons and Frisians) [SCHMIDT WILHELM. 1976: 45]. It is supposed that a common language for all Germanic people existed till the 3rd cent. AD and it was split after the migration of Germanic tribes into Central and North Europe [Ibid: 44]. But the analysis of Germanic languages by the graphic-analytical method brings us to different conclusions.

Initially, such modern Germanic languages were used for analysis: German, English, Dutch, Swedish, as well as the dead Gothic. Later, the Swedish language material was supplemented with vocabulary from other North Germanic languages, and Frisian was also involved in the study. Based on the analysis of the etymological dictionaries of the German, Old English, Gothic, and Dutch languages [А. KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR, 1989; VEEN P.A.F. van, SIJS NICOLINE van der, 1989; HOLTHAUSEN F., 1934; HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974] and bilingual dictionaries of other Germanic, mainly North Germanic languages the Table-dictionary of the Germanic languages was compiled and then used for calculating. This Table-dictionary is among others filed on Etymological Table Database). The list of Germanic phono-semantic sets consisted of 2628 units. 1424 of them were admitted to be common Germanic words and the rest were systematized according to matches. Then the number of mutual words in the individual language pairs was calculated and the result is presented in the table.

Table. Number of mutual words in pairs of Germanic languages

| Languages | German | English | Netherl | Dutch | Gothic | Frisian |

| German | 884 | |||||

| English | 601 | 858 | ||||

| Dutch | 503 | 357 | 632 | |||

| Norse | 412 | 468 | 226 | 651 | ||

| Gothic | 228 | 205 | 132 | 166 | 305 | |

| Frisian | 248 | 237 | 245 | 128 | 82 | 329 |

Using these data, the model of the relation of the Germanic languages was built quite easily (see Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Graphic model of Germanic languages relationships.

After repeated additions to the Table-dictionary of the Germanic languages, the scheme of kinship was not changed. The location of the English, German, Dutch, and Norse languages was always the same but the reliable placement of the Gothic language on it was not succeeded because of insufficient data.

Since we have only four reliable nodes of the graph, it is very difficult to find a proper location for the model on the map – a variety of locations are possible as the total number of languages is relatively few. A found position will be more veritable if it will be confirmed by other facts. Let us admit such location of the model that the area of Anglo-Saxons lies upon the Urheimat of Italics between the Teterev, Pripyat’ and Sluch (rt of the Pripyat') Rivers. In this case, the area of the ancestries of modern-day Germans (let us name them for convenience Teutons) can be located on the ethno-producing area between the Sluch, West Bug and Pripyat’ Rivers. The ethno-producing area on both sides of the West Bug is suitable to the ancestors of the Dutch people (let us name them for convenience Franks). Accordingly, Norsemen had to take the ethno-producing area between the Pripyat, Dnieper, and Berezina Rivers where the Greek language was formed earlier [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 45]

This assumption is confirmed by effecting the Greek substrate on the language of the Norsemen, from which it penetrated also in the Ukrainian language as the ancestors of Ukrainians occupied the same area later [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2000: 9].

Undoubtedly, a substrate word of this area is *krene "a well, source" (Ukr. krynytsia and Br. krynitsa), though most experts deny their connection with Gr. κρηνη (Aeolis κράννα) “the same” [VASMER MAX. 1967: 377]. However H. Frisk and F. Holthausen connected this word as Gr κρουνός "source, flow, stream, spray" with Old Norse hrønn "wave", OE hræn "wave, flow, sea" [FRISK H. 1970., HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974:146]. Clearly, the Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons have adopted this word from the remnants of the Greek population, and from them, the word in a narrower sense has been got by the ancestors of the Ukrainians, who have added the Slavic suffix –itsya to it, and then the Russians, Poles, and Belarusians borrowed the word from the Ukrainians. Other examples of possible Greek-North Germanic substrates:

Gr. βλεμμα “look, eyes” – Old Norse blim-skakka “to squint” (Old Norse. skakka “curvature”) – Ukr. blymaty "to shimmer, glimmer".

New Gr. γλεπω ”I watch” – Dan. glippe, Sw. glippa “to blink, watch” – Ukr. hlypaty "to see, look".

Gr. κωβιοσ “gudgeon” (Gobio gobio) – Old Norse. kobbi “young seal”, Sw. kobbe “seal, sea-dog”) – Ukr. kovbyk “gudgeo”, Bel. kovbel “the same”. Similar words are present in the Baltic and Russian languages (А. LAUČIŪTĖ Yu.A., 1982, 143), but phonetically they are standing on. Perhaps it is an errant word.

Gr. σκαπερδα "a game of boys while Dionysius” – Icl skoppa “ricochet” and jörðin “earth”) – Ukr skopyrdyn “some game, during it a stock is thrown to be struck on the earth with both ends in turn”.

Gr. σμῶδιξ "a stripe" – Icl. smuga “small valley” – Ukr. smuha "a stripe".

Gr. χαρισ “beauty” – Old Norse hannr "skillful" – Ukr. harniy beautiful.

Taking the above-mentioned placement of the Germanic languages, we see that for the Gothic and Frisian, there was only one free area between the upper Pripyat and the Neman, from the Yaselda to the Sluch River. Locating here the Urheimat of the Goths, Vandals, and Burgundians is in discrepancy to an insufficient number of common words between the Dutch and the Gothic language. This makes us believe that these old Germanic tribes could not be the neighbors of the ancestors of the Franks. Between their areas had to be located a tribe of another language. Maybe it was the ancestors of the Frisians. The number of common words between the Frisian and other Germanic languages does not contradict this hypothesis. In this situation, the problem might be solved so that the Franks occupied territory not on both sides of the Western Bug, but only of its left bank and the right bank should have been settled by the Frisians. Localization of the ancestral home of the Goths on the territory of Belarus is confirmed by the Lithuanian name of Belarusians Gudai, that is Goths (VASMER M. 1964: 400). Then common Germanic territory could be presented as on Map 8.

Map 8. Germanic languages in II mill BC.

However, there is a possibility that the mutual relations of the Dutch and Gothic languages have not been studied sufficiently. Founded separate lexical matches may indicate a closer relationship between them as it was previously thought. For example, let us consider, such phonetic correspondence: obsolete Dt. eiber "stork" – Goth. aibr "victim". Storks are considered by many folks as sacred birds, symbolizing abundance, fertility, and longevity. According to Armenian mythology, storks are in their own country people, farmers who before flying back sacrifice one of their chicks (ARUTIUNIAN S.B., 1991, 105). Many European nations believed allegedly storks, throwing out of the nest of one of their chicks, bring it to the victim. The ancient Germans believed that storks one of the packs as a victim before leaving. That is semantic correspondence between the words victim and stork is possible. There is a good phonetic matching in names of alder in the Gothic and Dutch languages: Got. *alisa, Dt. els (Ger. Erle).

There is historical evidence of the presence of the Germans on the territory of Ukraine, referring to the time when they went away from here, but their name was transferred to the Slavs settled on the old Germanic Lands. In 970 the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces (969 -976) reported the Kyiv prince Svyatoslav (964 – 972) through the Ambassador's message, which consisted of the following words:

I believe that you have not forgotten about the defeat of your father Ingor, who despising an oath sailed to our capital with a huge army of 10 thousand ships, but returned to the Cimmerian Bosporus with barely a dozen boats, being himself a messenger of his misfortune. I do not mention anything about his [further] miserable fate during a campaign against the Germans when he was captured by them, tied to tree trunks, and torn in two. (LEO the DEACON, 1988, VI, 10).

It is clear that we are talking about Prince Igor, martyred by chieftains of the tribe Drevlians inhabiting the Anglo-Saxon area at that time. The Anglo-Saxons remained on the Ukrainian territory until the "Great Migration." In this regard, the origin of the ethnonym “Drevlians "can be output from the name of a known Germanic tribe Turvin [YAYLENKO V.P. 1990: 116}. The Drevlian tribe didn't belong to the ancient Rus’ state for a long time. They were included in it at least in the 10 century, as it was repeatedly stressed by A.N. Nasonov [NASONOV A.N. 1951: 29, 41, 55-56). The fact that the Vikings could not include the Drevlyans adjacent to the Polans in the "Russian land" can indicate that these were the remains of their relatives Anglo-Saxons, mixed with the alien Slavic population. The chronicle notes that the custom of the Polans was "meek and quiet", whereas Drevlians "lived bestial way", ie they were more belligerent or unruly.

Location of areas of the formation of the Germanic languages is confirmed by place names left by Germanic tribes (more on this in sections Ancient Teutonic, Gothic, and Frankish Place Names in Eastern Europe., Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Eastern and Central Europe, Norse and Gothic Place Names in Belorus, Baltic States, and Russia) in those habitats that have been identified as the Urheimat of the Teutons (as we call the ancestors of the Germans), Netherlanders (conditionally Franks) and the Frisians, the Anglo-Saxons, Goths, and Scandinavians. Moreover, sometimes place names even mark the migration ways of Germanic peoples to their places in modern settlements. This is especially clearly seen for the Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons. The map below shows the place names in the areas of formation of the the Germanic languages and in their vicinity. Maps of Norse and Anglo-Saxon place names submitted separately in the appropriate sections.

Germanic place names in Eastern Europe

On the map, settlements are indicated by asterisks.

Teutonic place names and the Urheimat of the Teutons are tinted red color.

Frankish place names and the Urheimat of Franks and Frisians are blue.

Gothic place names and the Urheimat of the Goths are tinted green.

Norse place names and the Urheimat of the Norsemen are brown.

Anglo-Saxon place names are orange. The Urheimat of the Anglo-Saxons is tinted yellow.

Hydronyms are indicated by blue circles and lines.

And now let us try to confirm the accuracy of such location of the areas of the formation of the Germanic languages also by their correspondences with distinct Iranic languages, which areas we already know (see the section Iranic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age ).

Germanic and Iranic habitats.

Legend: Afg – Afghani, Gil – Gilanian, Pamir – Pers – Persian, Yagn – Yaghnobi, Yazg – Yazgulami.

A representative sample of 334 German-Iranic isoglosses was drawn up on the basis of comparative analysis the Table-dictionaries of Germanic and Iranic languages. In fact, they are more numerous and the data submitted below only reflect their proportion according to the individual languages. Held count from the sample showed that the German language has 160 matches at least with one of the Iranic languages, English has 204 matches, Swedish has 204 ones. Ossetic has 157 Germanic matches most of all among the Iranic languages, it is followed by Kurdish – 107 matches, Pashto – 97, Persian – 79, Yaghnobi – 63, Talyshi – 61 ones. Data on the number of mutual correspondences between individual Iranic and Germanic languages are shown in Table 11.

Table 11: Number of mutual lexical correspondences between the individual Germanic and Iranic languages

| Lang | Osset. | Kurd. | Pashto | Pers. | Yaghn | Tal. | |

| All | 157 | 107 | 97 | 79 | 63 | 61 | |

| Swed. | 204 | 134 | 92 | 66 | 63 | 52 | 51 |

| Eng. | 204 | 120 | 82 | 82 | 59 | 49 | 45 |

| Germ. | 160 | 105 | 64 | 55 | 45 | 35 | 32 |

From the data in the table, one may see that the closest language contacts were between the ancestors of the Ossetians and the Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons. Connection of the Ossetian language with Germanic and especially with Old North Germanic (Norse), expressed in quantitative terms, gives the Ossetian linguist:

According to our calculations, a significant number of words are found in Ossetian which reflect the genetic relationship with the Germanic languages: Ossetian – Gothic isoglosses about 180, Ossetian – Norse – over 130, Ossetian – Norwegian – about 70, Ossetian – Swedish – over 60, Ossetian – Anglo-Saxon – not less than 120, Ossetian – English and Ossetian – Old High German – on 160… The greatest number of convergences is noted between Ossetian and German languages – about 400 (KAMBOLOV T.T. 2006: 24)

There are two notes to the calculations. First of all, it should be said that they do not reflect the "genetic relationship" of the Ossetian language with Germanic, but the language contacts caused by the proximity of the Ossetian ancestors to different Germanic people at different times. Otherwise, the origin of the Ossetian language may seem more complicated than it really is, if the chronology of lexical convergence is not taken into account. Secondly, the calculation technique is unclear. The author gives the number of words for the Norse languages, and then for the Norwegian and Swedish languages separately. It becomes unclear whether the number of words of these two languages is an addition to the number of Norse words or they are their part. It seems that the author understand the genesis of the Norse languages completely in a special way, like an intricate idea of the genesis of the Ossetian language. The same can be said about the Anglo-Saxon and "German" languages. In this regard, it is almost impossible using Kambolov's data to accurately localize the ancestral homeland of Ossetians, although in general they can confirm the neighborhood of the areas of Germanic languages with the Ossetian area in the case when its localization is known.

The areas of the Norse and Ossetians languages bordered on each other, but the Ossetians closely contacted with the Anglo-Saxons and Goths in later times (this is discussed in sections "Anglo-Saxons in East Europe" and The Ethnic Composition of the Population of Great Scythia According Toponymy. ). Also close neighbors of Ossetinas were Balts, who took Tocharish area between the Dnieper and Berezina Rivers. Examining the Ossetic-Baltic and Ossetic-Germic linguistic contacts, V. Abaev came to the conclusion that the ancestors of Ossetians borrowed agrarian culture from the West, because excepting the names of millet jäw, the Ossetian language has no word of agricultural terminology of Iranic origin. Among many other Ossetian loan-words from the Germanic and Baltic languages, V. Abaev gave a series of agricultural terms: Osset. xsyrf "a sickle" has matches in Baltic, Germanic; Osset. fsīr "an ear" – in Germanic; Osset. fsondz "yoke" – in Baltic, Germanic; Osset. stivz "a join-pin" – in Germanic; Osset. fäst "a mortar" – in Slavic, Baltic; Osset. tilläg "harvest" – in Germanic. Ossetian has borrowings in the building sector (Osset. räf "rafter" – Sw. raft "rafter" etc.) In general, the Ossetian-Germanic relations have been studied fairly good (A. ABAYEV V.I. 1958-1989, ABAYEV V.I. 1965), but less attention has been paid to the close linguistic relations of Ossetian with the Norse languages. For example, he did not see the connection Osset. fyd "flesh" with Sw. föda and Eng. food and made more reference to the German language, although the Teutonic area was lying much further than the Norsemen and Anglo-Saxon, and, accordingly, the Teutonic-Ossetian connection could not be closer. Obviously, Abaev had previously formed his own idea of the Germanic tribe with which the Ossetian ancestors were supposed to be in close proximity.

In generally V. Abaev attributed Ossetian-Germanic language contacts to the Scythian-Sarmatian time. However, this is true only for some English-Ossetian and Gothic-Ossetinan lexical matches, as the Anglo-Saxons were present on the territory of eastern Ukraine in the Scythian and the Goths in Sarmatian time, as well as the ancestors of Ossetians, while the other Germanic tribes had already left the territory of Ukraine.

The next on the number of lexical correspondences with the Germanic languages is Kurdish, although its formation area was far away than the areas of the Yagnobi and Pashtun languages. This contradiction is explained by the fact that, as we shall see, the ancient Kurds at one time moved to the right bank of the Dnieper, and there had stronger language contacts with the Germanic peoples than with other Iranic ones.

The area of initial formation of Proto-English was near-by to the Yaghnobi and Pashto areas, therefore English should also have many common language connections with Pashto and Yaghnobi, but connections of Germanic languages with these Iranic languages are perhaps yet to be investigated. Detailed study of these connections can provide linguists with rich material for the further research. The Yaghnobi vocabulary is scanty represented in the Table-dictionary because the lexical material of this language was taken from an available small dictionary. Nevertheless, interesting examples of the isolated matches of this language with the North Germanic and English languages were discovered:

Eng. bug – Yagn. bugalak “gadfly”;

Eng. cog – Yagn. ozax “tooth”;

Eng. jump – Yagn. jûmb “to move”;

Eng. moth, Swed. mott, Ger. Motte – Yagn. mоtta “bread moth”;

Swed. digna “to fall”, dingla “to hang over”– Yagn. dangal “fell”;

Swed. mögel “mould” – Yagn. magor “mould”;

Swed. sarg “edge” – Yagn. sarak “edge”.

The Pashto area was located as nearest to the English one and this was resulted in such English-Pashto matches:

Table 12. English-Pashto lexical correspondences.

| English | Pashto |

| OE, Eng. beam, Ger Baum a.o. Gmc "a tree" | bêna “a tree” |

| Eng. dapper | debər “stout, fat” |

| OE fright, Eng right | rixtija “truth, verity”; |

| OE gǽt, Eng. gate | get. “gate” |

| AS quest "leaf broom", Ger. Quast “brush” | γōšt “millet” |

| OE lyft “weak, foolish”, Eng. left “left” | lavt “weak” |

| Eng.-Sax. minnia (Ger. Minne) “love” | mina “love” |

| OE gnagan, Ger. nagan “to gnaw” | ngardəl , Osset. nyqqyryn “to swallow” |

| Eng. rate “to scold” | ratəl “to scold” |

| Eng. to search | surag’, Pers. sorag’ “to search” |

| O.Icl. scìr a.o. Gmc “clean, white, bright” | x.kāra “clear, bright” |

| OE spearca, Eng. spark | spərəgəj “spark” |

| Eng spring | spərγa “spring” |

| OE wadan “to go forward”, Eng wade | wāte “exit”, watəna "going out" |

| OE weddian “to pledge, marry”, Eng. wedding | vādə “wedding” |

| Eng. wherry “a boat” | bərəj, berrah “raft” |

| OE wīd “wide” | wīt “wide” |

An enigmatical match is Afg. panga "capital" and OE pæneg "coin, money" which has some correspondences in other Germanic languages, the origin of which is considered unclear (Ger. Pfenning, Swiss pengar, Dan. pengeetc.). This issue requires a separate study. The Germanic-Iranian linguistic relations have not yet been sufficiently studied what is confirmed by the fact that in the etymological dictionary of German (A. KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989) many ancient Germanic words are presented with the mark "unsicher" (unclear) but Iranian matches are almost never given, though they are sometimes completely transparent. However Pashto has many English loan-words of modern days, such as Pashto bench (Eng bench), Pashto strābari (Eng strawberry) etc, therefore it is very difficult to separate common ancient lexical heritage from nowadays borrowings. Some lexical correspomdences can have common origin from Greek or Latin. One must say that English-Iranic connections are not yet studied sufficiently. For example, Eng. hog is supposed to be of Celtic origin but it has many matches in the Iranic languages, which are unknown (Yagn, Afg xug, Shung xūg, Gil xuk, Pers. xūk, Yazg. xəg etc) for scholars. Many Germanic words have Iranic matches (Ger Damm, Sw damm “dam”, Ger Faß "barrel”, Haus “house”, Hammel “lamb”, Rain “border”, Reif “rope”, waten “to wade”, Zagel, Sw tagel “tail”) but it is vainly to look for them in the Etymological Dictionary of German Languge

Besides, there are such Germanic-Iranic parallels which connection is not clear. For example, Ger Bast, Eng, Dutch, Ic bast "bast, bast rope" correspond with the word bast “to join” which is present in many Iranic languages, Ger Hirse, OS hersija “millet” can be connected with Kurd herzin, Tal arzyn, Pers ärzan “millet”. But the most interesting example is such Germanic-Ossetic parallel: Ger Farbe, Dutch verv “paint”, Sw färg “color”, Got farwa “deportment, carriage, color”. They come from Gmc. farwa-/ō "shape, color" (ibid, 202). One cannot at once to find a match to them fallow in English. All these words can be united by Os färw “alder-tree” which has no Iranic parallels. It is known that the bark of this tree can be used for painting and gives red-yellow or brown-yellow color. Maybe Ger Falbe “a dun, light-bay horse” belongs to this word group. V.I. Abaev considered the Ossetic word as a loan-word from O.U.G fеlawa “willow-tree”. In such case, Slav. vьrba, Lit virbas “vine”, Lat verbena have to be joined here too. Ger Falbe is connected by Kluge with Gmc *falwa “light-yellow” parent Slav. *polvь, Lit palwas. As you can see, the semantics of the words of this root is extremely branched and comes from the Indo-European roots, so in this case, the term "Germanic-Ossetian parallel" is conditional, since it is difficult to determine exactly where you want to restrict the semantic field. Consequently, the element of subjectivity in the research of this kind can not be excluded but when the linguistic facts are put in a certain system, then it becomes more or less clear what the words refer to an older layer, and which are the product of further development, and it helps us to carry out research at different levels, although it is not always possible to determine the word set level.

The ancestors of the Balochs should have had linguistic contacts with the Germanic tribes too, and their traces could survive to this day. You can purposefully look for them and you can find something. For example, the Germanic *þaka (German Dach) "roof" has a correspondence in Bel. Dakk "to cover". There is no similar word in the English language, from which the Balochi could borrow this word.When we reviewed the kinship of Indo-European languages, it was possible to note that the Germanic and Iranic languages have somewhat more common words than it should have been based on the distance between the location of their habitats. Now it is clear that earlier in the table-dictionary of Indo-European languages, we introduced some words common to the Germanic and Iranian languages, which do not refer to the time of all Indo-Europeans staying in their ancestral homeland. They appeared when the Germans and Iranians, expanding their territories, entered into closer contact. Accordingly, we have to remove the asynchronous word nests from the table-dictionary. The criterion for withdrawal may first of all be the prevalence of a word in related language groups. For example, if the word is very common in the Germanic and Iranian languages, then with a high degree of probability we can talk about its belonging to the level of Indo-European relations. If a word is widespread in one or two languages, and even more so in the languages of neighboring areas, then there is reason to consider it to come from later times, and, accordingly, it should be transferred to a higher-level table. For example, Osset. läsäg "salmon", which has matches in the Germanic, Slavic, Baltic, and Tocharian languages, was included in the table of the Indo-European relations as an Iranic word. The other Iranic languages have no reliable correspondences, but they could disappear. Now, when we see that the ancestors of the Ossetians dwelled side by side with the Balts and Germanic peoples, we have reason to believe Ossetian word borrowing in more recent times, to remove it from the table of the lowest level and include it in the table of a higher level. In doing so, we can gradually more clearly stratified vocabulary studied languages on levels, determine the range of words without reliable etymology and further explore them in the light of semantics, historical and geographical circumstances, etc. Such studies may lead us to reconstruction at least in general terms of "dead" languages of the Palaeo-European population, Trypillians etc.

As we can see on the map 5, the forefathers of Albanians, the Thracians were the nearest neighbours of Germanic tribes on the southeast. The Pashto Urheimat was located over the Dnepr. All these languages can have common lexical heritage. However the Germanic-Thracian language connections are researched insufficient, to say nothing about Pashto-Albanian ones. Brief survey of the vocabularies of these languages shows that such connections exist. The Pashto-Albanian lexical matches were considered above, there are some English-Albanian examples:

Eng beam – Pashto bêna - Alb pemе “a tree”;

Eng blay, Ger Blei – Alb – bli “sturgeon”;

OE borgian, Ger Borg – Alb barga “debt”;

Eng raft, Ger Drift – Alb trap “a raft”;

Eng deer – Alb drё “deer”;

Eng trunk – Alb trung “a stump” (though both can be from Lat truncus);

Some Albanian-Yagnobian matches were found too: Alb hingеllin “to neigh” – Yang hinj'irast «id», Alb anё “bank, shore” – Yagn xani «id», Alb kurriz “back, spine” – Yang gûrk “id”.

The Germanic territory coincides to a great extent with the region of Trzciniec culture of uncertain origin which existed from the second quarter till the end of the 1st mill BC. Thus, this culture can be plausibly considered as of Germanic origin. Such an assumption may be confirmed by connections of discrete Germanic languages with the Iranic ones since the Iranic areas were located near-by on the Dnieper's left banks.

Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names. .

Ancient Teutonic Place Names in Volin .

GERMANIC TRIBES AMONG SARMATS