The First Great Migration

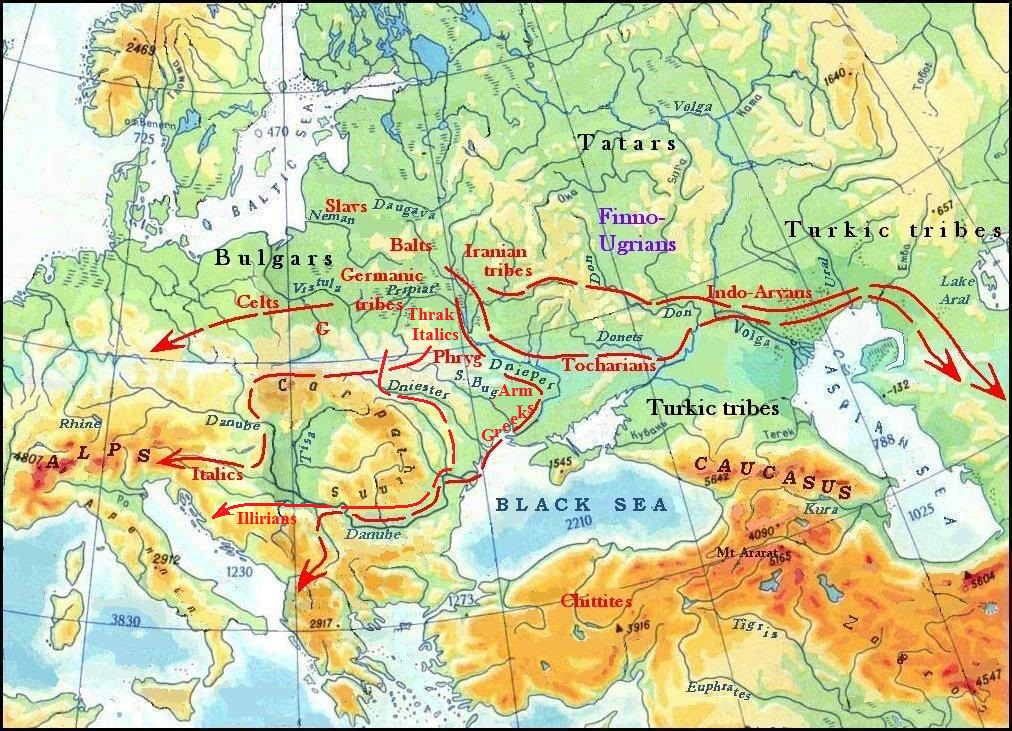

Having sketched a general scheme of movement of Indo-European peoples in Eastern Europe at the turn of the 3rd-2nd mill BC (see the section Migration of Indo-European Tribes…), let us try to recreate the picture of migration of the local population more detailed. While the development of sheep breeding, increased livestock of Turkic settlers of the Dnieper-Don-Interfluvial area have necessitated mastering new pastures (see. Section Ethnicity of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures…), one of the reasons for the relocation of the Indo-Europeans was relative over-population of their territory between the Vistula and Oka Rivers. Fishing as a basis for management provided a stable and reliable source of food for the local population therefore their numbers gradually increased, leading to specific demographic stress. The beginning of the Migration was attributed to the natural conditions of Europe:

Although a huge space, today turned into a cultural and densely populated country, was covered with virgin forests and impassable bogs, this was not a significant obstacle. The extensive system of rivers, which ensured moving on canoes and rafts at any time of the year, everywhere provided an opportunity to develop a new space. Water was everywhere, and there was no arid land or desert here. The summer in Europe was not murderous heat and even winter here was not so severe to be an obstacle to residence [Krämer Walter. 1971, 22].

It should be emphasized that during the migrations of ancient peoples, not the entire population was leaving their ancestral home. In particular, as W. Porzig thought, this had no apparent reason for Indo-Europeans [PORZIG W., 1964: 97-98]. Most likely only the surplus population moved away to new lands, and a pretty big part of it, especially in isolated areas should be retained. After the coming new alien population, the remnants of the previous one were assimilated by them to some extent impacted the language of the new arrivals, ie, the effect the principle of superposition had a place. Substrate effects on the example of individual languages are considered in the section Language Substratum. On the other hand, with migration, for different reasons, from time to time some part of people stayed permanently in convenient locations while the majority moved on.

Thus, the movement of the peoples of those times was no resettlement in the full sense of the word. Correctly to call it the scattering. It does not go without military conflicts, but cultural contact of the aliens with autochthonous populations was inevitable. In particular, the close cultural exchange took place during the settling of the Turks on the Trypilla culture space when they began to move to the right bank of the Dnieper searching for free land.

Natural conditions, not only contributed to the migration of the population but also determined their direction. It is understood that the forest area hampered the resettlement of people and the most convenient way was through river systems [GOLUBOVSKI P. 1884, 13]. Boating on rivers was realized by dugout canoes hollowed out tree trunks (see the photo of a Slavic dugout boat from the 10th century at left). In the steppe zone, where rivers flow more in the meridian direction, the need for resettlement pushed people to seek other means of transportation. So inhabited steppe Turks came to the invention of the wheel.

Initially, for the transportation of people and goods, sleds were used, laid on two logs, having been transformed over time into wheels. Since the time of G. Childe, the hypothesis of the monocentric origin of the wheel and carriage, which took place in Asia Minor, prevailed. However, there are other assumptions, and "in principle, the invention of the cart could have occurred in any region where the ard and sleds were known", including Eurasian steppes (KUZMINA E.E. 2010, 7).

Turkic languages have common word čana “sled”. The Turks were the first who domesticated the horse and used it as draft animals to transport things on sleds. Since sleds are ineffective in summer, the Turks made their resettlement probably in winter, until the wheel was invented. The invention of turning movement (rollers and similar) and use it for transportation occurred at different peoples at different times [ZVORYKIN A.A. a.o. 1962, 55]. The idea of using the wheel emerged among the creators of the Pit culture too regardless of external cultural influences (NOVOZHENOV V.A. 123 2012). Disc wheels found in tombs evidence using wheeled transport by the Turks.

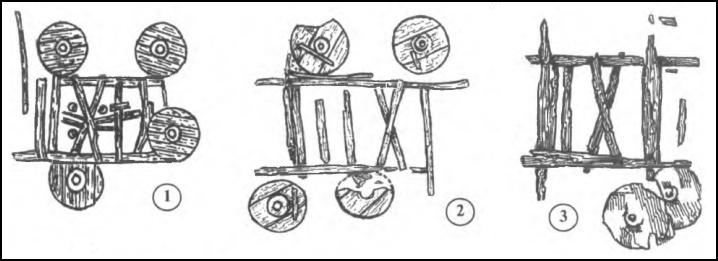

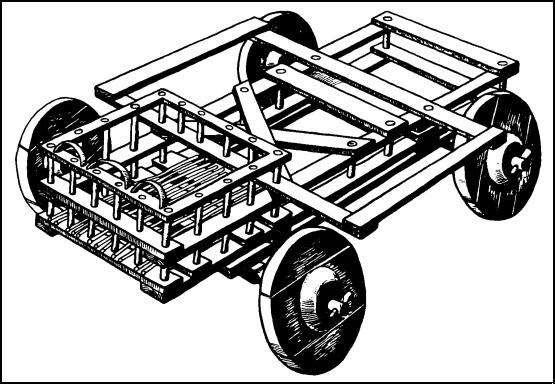

Wooden carts of Pit culture time.

1. – Novotytarovskaya (Dinsk district of Krasnodar Krai). 2. – Ostanniy burial mound. 3. – Chernyshevskiy burial mound (Steppe Kuban').

(KULBAKA V., KACHUR V. 2000: 54)

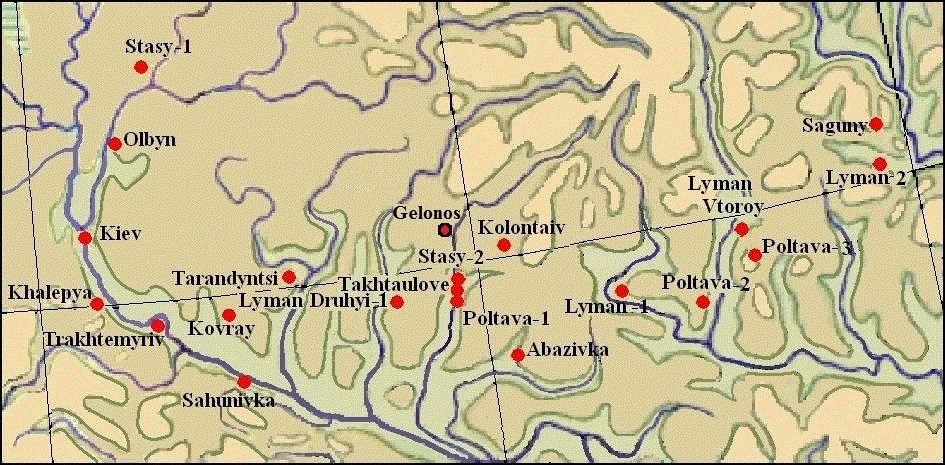

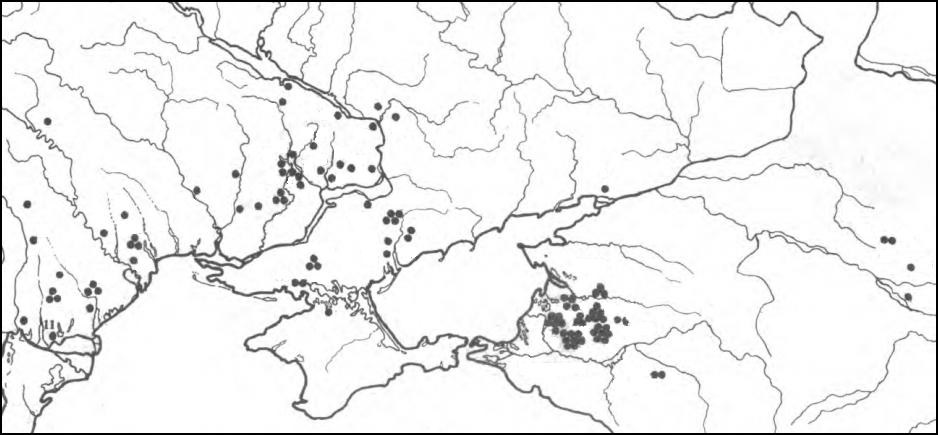

At right: Map of finding wooden carts in tombs of Pit culture time (32-30 cen. BC). Southern Ukraine and next space (ibid: 58)

The wheel and the cart were a further improvement of the roller. Therefore the first wagons were too heavy-handed, as the wheels rotated with the same speed, being firmly planted on the axis which turned together with the wheels. Such primitive carts could move by a straight road for a small distance. However, with time the axis and wheels were separated. The wheels were set on a fixed axle, allowing them to rotate independently of each other at different speeds.

At left: Reconstruction of the wagon of Novotitarovskaya culture.

The reconstruction was made on materials from burials 150 and 160 of the I mound of Ostanniy remains (GEY A.N. 1991: 64).

As you can see at left the wagon of this type has a complicated design with standard sizes of parts.

The tripartite wheel with a 7 cm thickness and a diameter of about 70 cm had the hubs on both sides. Axis quadrangular sections were built into the frame and the wheels with round ends were fixed on them by a cotter and rotated freely. The method of fixation of axes excludes the presence of a rotator, ie the wagon could not provide a sharp turn. Draft animals (bulls or oxen) were harnessed on both sides of the drawbar with a forked end that was fastened to the frame (ibid, 64-65). This design has made it possible to travel long distances. During this movement in different directions, different versions of the Corded Ware culture (CWC) were developed in Europe based on the Pit culture influenced by local conditions and Asian culture of different types. Some differences in the cultural types of CWC can be explained by the non-simultaneous start of the migration.

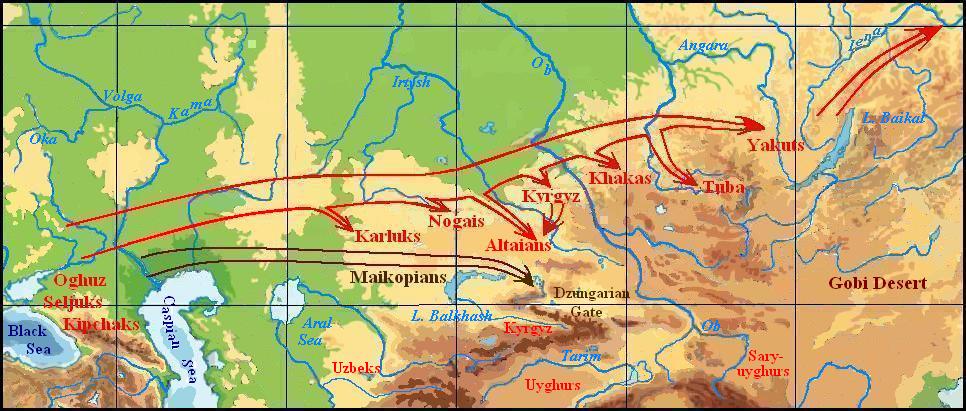

Eastern Europe was settled by Turks in multiple streams bypassing settlements of Indo-European and Finno-Ugric peoples (see map at left).

Only a part of the Turks inhabiting the left bank of it moved westward, crossing the Dnieper River. They were the language ancestors of the modern Chuvashes, Turkmen, Turks, and Gagauzians, whose areas were determined by graphical-analytical method on the left bank.

From the steppes, this part of the Turks moved further along the left bank of the Dniester and the northern spurs of the Carpathians, leaving their settlements in Right-bank Ukraine and Eastern Poland. Their languages preserved archaic features of the Proto-Turkic language for a long time because they lost contact with the rest of the Turkic languages, which continued to develop in close contact with each other in the old places. Most of the migrants to Central Europe and the Baltics were eventually assimilated among Paleo-European aborigines and later among Indo-Europeans, but due to historical circumstances, the Proto-Chuashes retained their ethnic identity and, along with it, the archaic of the Proto-Turkic language. Thanks to this, the Chuvash language helps us to track the paths of the Turks' wandering in wide space.

For lack of sufficient pasture in a wooded area, the migrants had to keep moving on. Thus populating the territory of Germany and the Baltic states, after a while, the Turks were moving also to South Scandinavia through the Jutland Peninsula and Finland (see the section Ancient Turkic Place Names in Central and Northern Europe ).

A small part of the Turks moving along the banks of the Desna River reached the space between the Volga and the Oka and populated it partially forcing out and partially assimilating the previous population. Here they created Fatyanovo culture as one of the variants of CWC. Another embodiment of this culture so-called Balanovo was established by that part of the Turks, who crossing the Don River, moved along the right bank of the Volga to the mouth of the Oka River. Turks Migration towards the upper Volga resulted in the motion of a significant part of the local Finno-Ugric population (see the section "The Expansion of the Finno-Ugric Peoples").

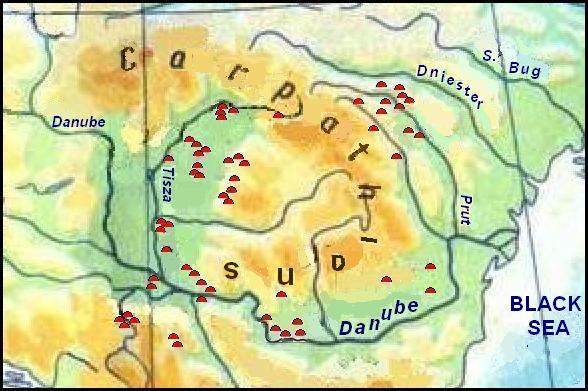

At the same time some groups of Turks moved on land towards the Balkans. As Elena Kuz'mina pointed out, the gradual infiltration of Pit tribes from the steppe zone to the area of the ancient agricultural cultures in Moldova, Romania, and Hungary occurred in the III mill. BC [KUZ'MINA E.E., 1986: 186]. Moving upstream of the Danube along its right bank, the Turks reached the mouth of the Tisza River and then turned north. They gradually colonized the left bank of the Tisza basin up to the Carpathians, which is the area of Cucuteni-Trypilla culture. The wetland between the Danube and Tisza remained uninhabited. Small groups of Turks settled on the right bank of the Danube.

Left: The cluster of mounds of Pit culture in the Carpathian region and the Danube basin. The map is based on Piotr Wŀodarchak's data (WŁODARCZAK PIOTR. 2010. Fig. 1)

European scholars, recognizing the great role of the Old-Pit historical and cultural region in the further history of Europe, unambiguously associate the population of this region with the Indo-Europeans. In particular, the following considerations are typical about the settlement of the Danube basin by Pit-people:

The western Black Sea region was the territory on which, beginning with the Eneolithic, mobile groups of Indo-European cattlemen moved in the southern and western directions. These routes passed through the Danube Valley (to the west) and the western coast of the Black Sea (to the Balkans). In the geographical (landscape) sense, these territories continued the Azov-Black Sea steppes, which stretched along the Danube to the lowlands of Central Europe (modern Hungary, Northern Yugoslavia, western Romania, and southern Slovakia). These are the territories that previously were occupied by agricultural tribes of the Balkan Peninsula and Central Europe. Penetration to these regions of steppe cattlemen of the Northern Black Sea Coast – Azov region largely determined the specifics of the formation and further development of agricultural and pastoral tribes, which is reflected in the term "Indo-Europeanization" [KULBAKA V. KACHUR V. 2000: 27]

Considering the Turkic ethnicity of the bearers of Pit culture, the meaning of this quotation has rightly to be attributed to the Turks. In addition, it contains a significant error. The settlement of Indo-Europeans in Europe is associated with the spread of CWC, which developed based on the Pit culture. However, the sites of CWC are not fixed in the Balkans.

Many researchers believe that the genetic roots of Cucuteni-Trypilla culture are hidden in the cultures of the Balkans, the lower Danube, and the Carpathian Basin, but not in the Neolithic of the Bug-Dniester basin; its ethnicity is considered to be unknown (ZBENOVYCH V.G., 1989: 172; Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 1. Pervobytnaya arkheologiya, 1985, K: 202-203). We hypothesized that the Trypillians could be Semitic people, and it is quite possible that their ancestors came to the Balkans from Asia Minor. There are some vague connections between the Balkan and Asia Minor cultures.

If the Trypillians, indeed, were Semites, then traces of their influence in the Turkic language have to be left because they were neighbors of the Turks. The Dnepr could not be an insurmountable obstacle, especially in the winter, so primitive trade and cultural exchanges between the Turks and Trypillians might take place. Let us look first at the traces of Trypillian influences in the area of trade, ie among the words that mean "commodity", "payment" and of that kind. A large nest of words having different options based on the root tavar was already been considered in the section “The Language Contacts between Indo-Europeans, Turks, and Finno-Ugrians in Eastern Europe”. Similar words were found in Hebrew: toar "a product", davar "a word", "a thing", and "something". Analogous Trypillian word could accept the sense of "goods" in the exchange process. Another hypothetical Tripoli word *kemel could mean "payment, indemnity" (Hebrew gemel "to pay back"). The similar word kěměl is present in the Chuvash language and means "silver". In full compliance with the phonology, it corresponds to the word kümüš of the same sense in other Turkic languages. Of course, silver could fulfill the function of money in ancient times, and the change of the sense of the word occurred from the fact that the trading parties do without an interpreter and, therefore the same object could become different senses. What for some was simply payment, for others took on a specific meaning of silver. Further searches yielded enough material, which gives reason to consider the Semitic origin of the Trypillians. This is detailed in the section "Hypotheses".

Trypillians had no tribal leaders, and the rules of life were formed by the priesthood in the general confessing cult of fertility, reflected in the image of women-mothers, as evidenced by found statuettes with accentuated feminine forms. Previously, even the view of the matriarchal society organization of the Trypillains was dominant, this could explain the mysterious disappearance of Trypillian culture. The dominant position of women in society came into conflict with the role of men playing a greater role in the household due to their physical superiority. Perhaps this internal crisis eased getting a dominant position in these lands for warlike nomads from the east without much exertion. Anyway, at that time Trypillian culture finally fell into decline however the Trypillian heritage left traces in subsequent cultures of this region, so we can assume that a large part of the population remained in their native places. This is quite likely because the Turkic riders could not recklessly exterminate peaceful dwellers. They confined themselves to plundering the local population and destructing their settlements [BRIUSOV A.Ya., 1952]

Along with the cult of the mothers, the Trypillians had the cult of the bull as masculinity, and both cults were somehow intertwined [ZBENOVYCH V.G., 1989: 165]. It is believed that the image of a bull and phallic saints as a symbol of male power has been brought by Pit people, as well as the patriarchal clan system, the cult of ancestors, and the funeral rites, were brought by them [ALEKSEYEVA I.L. 1991: 20-21].

It is possible that since the beginning of the late stage of the Trypillian culture (3000 – 2400 years BC), Indo-European tribes began gradually to settle among the ethnic Trypillians having already embraced the elements of this culture when it was spread to the Ros’ River and the middle Dnieper during the middle of its existence in 3600 – 3000 years BC (Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 1. Pervobytnaya arkheologiya. 1985: 211). Thus, the spread of culture came from the south-west to the north-east, but no invasion of the agricultural population from Trypillian culture was noted by archaeologists [KUZ'MINA E.E., 1986: 186].

The steppes were occupied by the Turks. Therefore the Indo-Europeans in search of free land were forced to move on, choosing the direction agreed upon in the arrangement of the previous places of settlement. Waterways can be used for moving. By the time the Dnieper River rapids were covered with water and did not interfere with boating, as Herodotus did note nothing about cataracts. The fact of a greater fullness of the rivers of Europe in ancient times is not denied by geographers, and a marked drop in the Dnieper level was noted, in particular, in 1815 (BELAKOV SERGEY. 2016: 222). Therefore, it can be assumed, the Greeks moved a considerable part of their way by water. While moving they established settlements that exist till now (Kyiv, Halep, Trakhtemyriv, Sahunivka). Having found convenient places to settle in the valleys of the left tributaries of the Dnieper, some of the Greeks stopped further movement and settled here, founding Khorol, Poltava, Takhtaulovo, and other settlements. Later, they had a great influence on the development of Timber-grave culture here (more detailed see the section Ancient Greeks in Ukraine ).

Ancient Greek place names in Ukraine

Meanwhile, most Greeks continued to sail to the mouth of the Dnieper. Having gained experience in the construction of boats and navigation, they continued their movement along the shores of the Black Sea. The Greeks call the seaποντοσ, this word is akin to the Slavic put' "way". Further, their navigation skills promoted them to the occupation of the Aegean islands. Having reached the mouth of the Danube, the Greeks came upstream to the Iron Gates, which made further navigation impossible, so they moved to the Peloponnese by land, inhabited before by tribes, apparently related to the Minor Asian. In any case, most ancient place names of Greece reveal features not native to Indo-European languages.

The Greeks came to Greece in three waves: first the Ionians, then the Achaeans, who were the first, and last the Dorians were. The Ionians turned into ruins the settlements of the previous settlers, whom they called Pelasgians, Carians, or Leleges. Dark memories of the mysterious Pelasgian tribe remained with the Greeks until classical times (HOFFMANN O., SCHERER A., 1969: 19). Under the influence of the Minoan culture coming from Crete, they participated in the creation of the Mycenaean culture, which existed in mainland Greece between 1600 and 1050 AD. In the 14th-13th centuries BC, the Achaeans began their expansion into Asia Minor, Egypt, Sicily, and the south of the Apennine Peninsula. This expansion is associated with reports from Egyptian sources about the invasion of "sea peoples". The Greek attack on Troy dates back to this time. Soon after the end of the Trojan War, around 1200 BC, according to archaeological data, some destructive phenomena took place in continental Greece, which are associated with the invasion of the Dorians. While the previous conquerors had largely adopted the Minoan religion, the Dorians retained the original Indo-European religion of their ancestors, and at least their aristocracy was fair-haired (RUSSEL BERTRAND. 1946: 29-30).

The second stream of Indo-European expansion was held by dry land southwestward to the shores of the Adriatic. Some data on the movement of the Illyrians in the Adriatic are provided by archeology. The ancestral home of the Illyrians was part of the dissemination area of the culture of globular amphoras. Traces of the penetration of its eastern group to the south between the Prut and the Siret rivers make us think that the Illyrians descended along the Prut River to its mouth, and further moved to the Adriatic coast along the Danube bank.

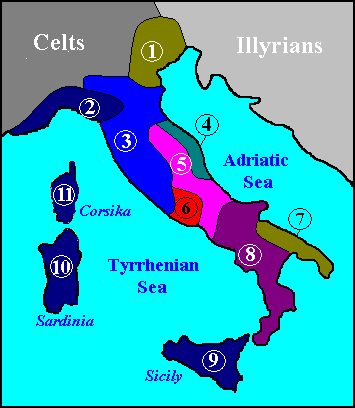

Obviously, this path of the Illyrians crossed somewhere in the upper Dniester with the path of the Italics, which included the tribes of the Sabines, Osci, Umbrians, Latins, and Falisci. For some reason, it was not used by them. They moved along the spurs of the Carpathians to the Yablunkovsky pass and through it got into Pannonia and in this way came to the sea, and moving further along the coast, reached the Padan Plain. They populated the Apennine Peninsula in several waves, the Latins and the Falisci perhaps remained for a long time in Pannonia.

At right: The people of Italy at the beginning of I millennium BC.

The numbers marked on the map:

1. – Veneti.

2. – Ligures.

3. – Etruscans.

4. – Sabines.

5. – Umbrians.

6. – Latins.

7. – Messapii (Iapygians).

8. – Osci.

9. – Sicani.

10. – Sardis.

11. – Corsi.

All this movement of Indo-European tribes southward could continue for several centuries, because the Phrygians and Armenians were joined in the general relocation process later. The fact that the Phrygians penetrated Asia Minor via the Balkans was confirmed in Greek legends. The Phrygians and mysterious Mushki came to the shores of the Sea of Marmara about the same time as the Dorians [BARTONÉK ANTONÍN. 1976: 60-65]. These Mushki could be a tribe allied to Phrygians, or one of their tribes, it could also be another name of Phrygians, but the fact that the Mushki moved to the headwaters of the Tigris later and settled there, let's suppose that these were the ancestors of modern Armenians. However, E. Tumanyan, referring to the Hittite and Assyrian-Babylonian sources, claims that the ancestors of the Armenians together with the "sea peoples" have appeared in the Chalis valley in the middle of the II millennium BC [TUMANIAN E.G. 1971]. Their nearness to the Phrygians was already discussed in the section The Areas of the Uprising of the Tocharian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian Languages. Since the Phrygians and Proto-Armenians appeared in Asia Minor in the middle (or end) of the II millennium BC, up to that time (not counting the time of the relocation) they had to populate the right bank of the Dnieper River as they stayed for some time in the Indo-European language space, to the south of the Thracians.

The Tocharians left on their Urheimat for some time, as evidenced by some linguistic matches with the Ossetians. V.Abaev gives such examples in his works:

Toch. witsako "root" – Osset. widag "the same",

Toch. porat "axe" – Osset. färät – "the same",

Toch. eksinek "pigeon" – Osset. äxinäg "the same",

Toch. aca-karm "boa" – Osset. kalm "snake",

Toch. káts "belly" – Osset. qästä "the same",

Toch. kwaš "village" – Osset. qwä "the same",

Toch. menki "smaller" – Osset. mingi "small, a little".

The bulk of Indo-Aryans were moving to Central Asia, crossing the Volga and Ural Rivers. However, some small part of them stayed in Eastern Europe forever. Clear traces of their language have been preserved in some Finno-Ugric languages for millennia. Such examples of Indian-Finno-Ugric matches given by T.T. Kambolov are the following:

Hung. tehén "cow" – OInd. dhenu "cow",

Mansi śiś "child" – OInd. śiśu- "child".

Mord. saras "hen" – OInd. śāras "motley" [KAMBOLOV T.T. 2006: 32].

The only among the Finno-Ugric languages Moksha vr'gaz "wolf" (in the Erzya language vergiz) may be added to these pairs as it is phonetically almost identically to Old Indian. vŕkas "wolf". Referring to E.A. Grantovsky, Kambolov also speaks of the reverse Finno-Ugric borrowings in the Indian, separate from the Iranian [Ibid]

In addition, there is reason to believe that languages of Sindo-Meotian tribes inhabiting the Taman Peninsula and adjacent areas, has genetic kinship with Indian:

Thanks to the works of O. Trubachev, hundreds of ancient linguistic forms were etymologized, and three extensive areas of Indo-Aryan linguistic relics were discovered in the Northern Pontic Region: Sindi-Meotian (Sea of Azov), Tauri-Scythian (Great Scythia) and Singane-Getic (Scythia Minor). The vast majority of Meotian linguistic relics are comparable with language materials of Indo-Dard-Kafir group of the Indo-European family. Already described and studied earlier language material is sufficient to conclude about the genetic kinship of the Sindo-Meotian and Indian [SHAPOSHNIKOV A.K. 2005: 32].

The split of the Indo-Aryan languages into two branches has occurred outside Europe, although, obviously, outside of India [ZOGRAF G.A., 1982: 112]. Such a division could occur somewhere at the first long stop, probably in Central Asia. Linguistic analysis shows that the creation of the Rig Veda took place not later than the 2nd mill BC, therefore, the movement of the Indo-Aryans from Central Asia or Northern Iran occurred before that time [LAL B.B., 1978: 47].

During the Middle and Late Bronze Age, about half a millennium (2250–1700 BC) in Central Asia, there was the Oxus Civilization, the main part of which is located in Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan, but similar cultural features are known in Tajikistan, central Uzbekistan (Zeravshan valley), as well as far beyond its borders, in a large part of eastern Iran and Balochistan (LYONNET BERTILLE and DUBOVA NADEZHDA A. 2921: 1).

This culture's last phase belongs approximately to 1800/1700 – 1500/1400 BC. Numerous transformations, "de-urbanization" in the final Bronze Age can be considered its "collapse", but it disappeared gradually. The combination of several social, material, and mental changes allows us to talk about mutation as a multifaceted, comprehensive, and deep evolution of the entire sociocultural system. Obviously, its occurrence is connected with the appearance of the Inloarians in Central Asia. This is evidenced by studies of ancient DNA, which testify to the significant role of northern populations in the genetic history of Central Asia(LUNEAU ELISE. 2021: 515). On the other hand, the presence of Indo-Aryans in Iran could be reflected by the special "Western Indo-Iranian language", noted near Iran and presented by the relatively small number of names of men and gods:

The area of these names coincides with the areal of the Hurrian language (from the foothills of Iran to Palestine) [DIAKONOV I.M., 1968: 29].

From Diakonov's arguments about the mass application of fight chariots by the speakers of this language, they came from the regions "north of the Caucasus" [Ibid: 30). Here it is necessary to say that the problem of migration of ancient Indo-Aryans is entangled by the generally accepted idea of the existence of a special Indo-Iranian (Aryan) language community. According to Harmatta, the advancement of the "Indo-Iranian" peoples from the steppes of Eastern Europe to Asia up to Hindustan and China occurred in two waves. The first wave took place at the beginning of the II mill. BC and the second did with the beginning of the 1st mill. BC. [HARMATTA J., 1981: 75]. Only the Iranian tribes should be considered with the second wave, and the first wave should follow the Turks that moved to Central Asia (see below).

Until now, there are theories of the autochthonousness of the Aryans in the modern places of residence of their descendants, and the number of their supporters is growing. As the works of recent years show, Indian scientists are especially zealous in this (WITZEL MICHAEL. 2012). The disadvantage of autochthonous theories is that they are closed within the Indo-Aryan question based on an unreliable localization of the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans and without connection with the established concept of their migrations to modern habitats. The belief expressed by other theorists that the "theory of the Aryan invasion" will eventually be rejected looks completely unfounded (HUL N.A. 2021).

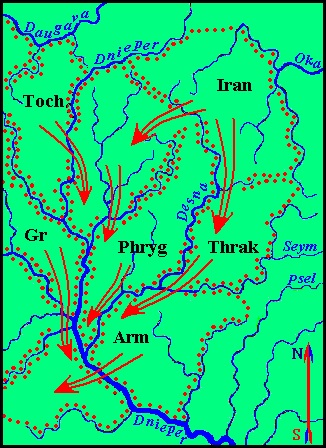

At right: Migration of Iranian tribes

The left areas of the Indo-Aryans, the Thracians (Proto-Albanians), Phrygians, and Armenians were occupied by the Iranians (see the map at right). Baltic people occupied the area of Tocharians after they departed away. Following the Phrygians, the Thracians crossed the Dnieper and settled for a long time on the Right Bank Ukraine, and from here, in the Pre-Scythian period advanced to the Balkans. The Celts, perhaps under pressure from the Germanic tribes began moving to the west, where they were the creators of Central European cultures of the Urnfield group (1300-750 BC), the north-eastern boundary of which seems to pass along the Neman, beyond of which the Slavic land lay. Germanic people have spread into the area of the Celts, occupied Greek areas, and southern areas of the Italics and Illyrians. During these migrations the Slavs also expanded their territory to the Baltic Sea, moving on the right bank of the Neman and thus establishing a direct language contact with the Celts.

The study of the Slavic-Celtic language relation was carried out for a long time by A. Shakhmatov locating the Slavic Urheimat on the Baltic shore somewhere not far from the Celts. Some linguists, among whom were such authorities as M. Vasmer and K. Buga, very critically regarded his claims about the special closeness between the Celts and Slavs [MARTYNOV V.V., 1983] but later Shakhmatov’s opinion was estimated more carefully:

A. Shakhmatov gives a significant list of alleged lexical borrowings in the Slavic language from Celtic, where a prominent place belongs to the public, military, and economic terms. The researcher also suggested that part of Germanic words entered the Slavic language through the Celts. Close Celtic-Slavic relationship facilitated conveying the ethnonym "Wends" on the Slavs [SEDOV V.V. 1983: 83].

V. Sedov, also noted that several authentic Celtic-Slavic lexical similarities were pointed out by J. Pokorny and H. Pedersen showed some grammatical parallels between Old Irish and Slavic languages. T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov gave examples of Celtic loanwords in Slavic: *sluga, *braga, *ljutь, *gunja, *dǫgъ, *tĕsto (GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984). The result of Celtic-Slavic contacts in phonetics was nasalization of vowels in Slavic languages, which developed in line with the whole process of monophthongization of Slavc diphthongs *en, *em, *on, *om and so at the tendency of increasing sonority in syllable structure, which led to the law of the rule of an open syllable (VINOGRADOV V.A., 1982: 303; KHABURGAYEV G.A., 1986: 94). As nasal vowels already existed in the Celtic, under its influence the monophthongization, in this case, went in the direction of the nasalization of diphthongs in closed syllables. This effect may be explained by dwelling the Celts and Slavs in the same phonetic area. According to S. Bernstein, T. Lehr-Spławinsky tried to explain the origin of the Masurian dialect by the Celtic influence. S. Bernstein also believed that "the Celtic influence on the Proto-Slavic language was deeper than it seemed so far" (BERNSTEIN S.B., 1961: 95).

V. Sedov believed that intensive Slavic-Celtic interaction took place with the reverse migration of the Celts from west to east, which began about 400 BC. As the creators of the La Tène culture, they made a great contribution to European culture, to the development of metallurgy and metalworking (SEDOV V.V. 2003: 4-5). Traces of this influence are noticeable in the Przeworsk culture, which creators considered by V. Sedov to be the Slavs, but in fact, they were Germans, and Celtic influence on culture and especially on the metallurgy of the Slavs is not visible at all. This is understandable – at that time Slavic-Celtic contacts could not be, they took place at a much earlier time, even before entering the Goths to the basin of the Vistula, separating the Slavs from the Celts forever. The ancestral home of the Goths was in the area between the upper reaches of the Pripyat and Neman Rivers from the Yaselda to the Sluch River, where they remained until the beginning of the I mill. BC. After that, they began to move westward on the land of the Slavs extended to the Vistula. Only in a few centuries, a new wave of Slavic migrants forced the Goths to leave the land and move along the right bank of the Vistula to the Volyn and further to the Black Sea steppes (see. the map below).

Wielbark culture at late Roman times [BIRBRAUER F. 1995, 37. Fig. 6, according to KOKOWSKI. Problematyka kultury wielbarskiej w młodszym okresie rzymskim].

The homelands of the Goths (the number I) and the Slavs (the number II] are marked additionally on the original map.

From Pliny the Elder ('23 BC – 79 AD), the ancient scholars (Tacitus, Ptolemy) placed the Venethi on the right bank of the Vistula River. Usually, in those days this name was associated with the Slavs:

… beginning at the source of the Vistula, the populous race of the Venethi dwell, occupying a great expanse of land. Though their names are now dispersed amid various clans and places, they are chiefly called Sclaveni and Antes (JORDANES. 1960. III. 35).

If the Vistula Venethi and the Adriatic Venethi were one nation or this is the consonant name of different or related tribes, has not been established to date. In this regard, the history of Slavic migrations in prehistoric times remains vague. You can assume that the Slavs were not assimilated by the Goths in the area of Wielbark culture, but were driven to the left bank of the Vistula, after which they continued their migration together with the Celts and reached the area that is now located in Venice

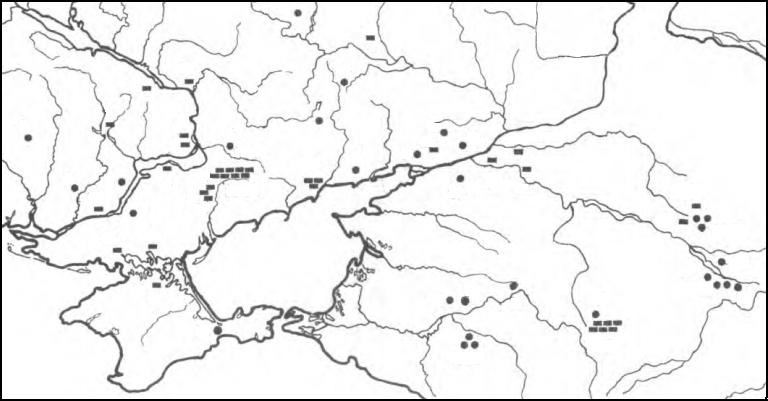

In comparison with the migration of Indo-Europeans, the Turkic expansion in the wide Eurasian space lasted much longer and covered the Pit and Catacomb periods. The remains of wooden carts and clay models of wheels, trolleys, and tent-carts were found on the territory of Ukraine and the North Caucasus in about 250 graves from the Pit and Catacomb time (KULBAKA V., KACHUR V. 2000: 27). At the same time, research shows that during the Catacomb period, the number of carts and model finds on Right-bank Ukraine and the Kuban has decreased significantly, but it has increased in the Kuma-Manych lowland what may indicate the termination of migration to Central Europe and an increase in the outflow of the population in the eastern direction (see the map below and compare with the map 32-30 above).

At right: Map of finds of wooden carts, wheels, and their clay models at Catacomb period (29-22 cen. BC) Southern Ukraine and adjacent territories (KULBAKA V., KACHUR V. 2000: 60)

Burials with characteristic cart attributes in the Don-Volga forest-steppe indicate that the second wave of Turks also followed the same path that the Fatyanovs and Balanovo residents had previously gone. On the territory of the Upper and Middle Volga region from the upper Oka to the Urals, in the second millennium BC., they became the creators of a new culture, which was called Abashevskaya. Archaeological finds, in particular, non-Abashevskaya type clayware in the cultural complexes of that time, are evidence that only military detachments moved through this territory from the south, and "there no inter-assimilation of full-fledged cultures took place, but rather a replenishment of the deficit of own "one-cultural" women by local ones" (MATVEEV Ju. P. 2005: 11).

However the main mass of Turkic people moved in search of new pastures behind the Volga in the steppes of Kazakhstan, and another part of them settled in Ciscaucasia, displacing the population of Maykop culture, which should also move to the left bank of the Volga and move further to the east.

At right: Settling of ancient Turks in Ciscaucasia.

The present population of the North Caucasus is multinational, but among it, there are Turkic peoples of Kumyks, Balkars, Karachais, and Nogais.

But only the Nogais have clear Mongoloid traits, while the other Caucasian Turkic people, just like the Turks, Azerbaijanis, Turkmens, and Gagauzes present the Europoid type. Mongoloid signs make themselves felt at the slightest cross-breeding, so there is great doubt that the ancestors of these peoples once were in the territory where the main population belonged to the Mongoloid race. In the works devoted to the anthropological appearance of the Turkmens, it is repeatedly noted that the Mongoloid features of some of the Turkmens are the latest layering of the Middle Ages, while the other part of them does not have an admixture of the Mongoloid component at all (DUBOVA N.A. 2009: 491, 501; DUBOVA N.A., BABAKOV O. 2016: 71-83).

According to the location of the areas of formation of the Turkic languages, the ancestors of the Caucasoid Turks had the ancestral homeland of the Seversky Donets and the Dnieper Rivers. The language ancestors of the Yakuts, Kirghiz, Kazakhs, Khakas, and Tuvans dwelled between the Seversky Donets and Don Rivers at the same time. That's it they had to move across the Volga to the east. In principle, the Chuvash and Kazan Tatars also did not have to have Mongoloid traits, but they appeared as a result of their metisation with Finno-Ugrians having Lappish features, or after the arrival of the Tatar-Mongols in Eastern Europe. The mixing of Chuvashes and Tatars with the Mongols could not occur on a large scale, nevertheless, the Mongoloid features of some Chuvashes and Tatars are quite noticeable. This once again shows how difficult it is to get rid of them. If ever the ancestors of modern Turks lived in the Altai, then their external appearance about this clearly shows. Thus, one can confidently say that not only Chuvash and Tatars, but also Turkmen, Cumans (ancestors of modern Crimean Tatars, Balkars, Karachais, Kumyks), Oguzes (ancestors of Gagauzians), ancestors of modern Turks and Azerbaijanis either always stayed in Eastern Europe, or did not go far from the Caspian Sea. It is impossible to explain otherwise some lexical phenomena that must have roots in the Proto-Turkic language, which were not preserved in the languages of those peoples who went to the east

In the culture and languages of many Turkic and non-Turkic peoples of the North Caucasus, some ancient Turkic relics have been preserved that are absent from other Turkic peoples. One of these terms has been preserved in the Karachay-Balkar, Ossetian, Abkhaz, and Kabardian languages as a reminder of the significant influence of ancient Turkic culture in the region of the Eurasian steppes (GLASHEV A.A. 2020: 102)

The same is also evidenced by Turkic place names (Terek, Beshtau, Ersakon, Kyzyl-Togai, Uchkeken, for example). "One hundred and fifty geographical names explained using the Turkic or Mongolian languages", exist only in North Ossetia (TSAGAEVA A.Dz. 2010: 97). A. Tsagaeva assumes that these place names were left by the Hunnic and Tatar-Mongol tribes, however, this statement can be fair only in part. Conquerors usually do not change the names of settlements. When the Ossetians came from the Don basin to the Caucasus, displacing or assimilating the local Turks, they either did not change the Turkic names or transferred them to the Ossetian, as, for example, the name of the Ursdon River, which is the calque of the Turkic Aqsu "White Water" (ibid: 18). According to Abaev's calculations, the number of common words in the Ossetian and Karachai-Balkar languages reaches two hundred. Their possible structuring is logical:

There are three main categories of lexical matches: elements borrowed from Ossetian into Balkar-Karachai, elements acquired from Balkar-Karachai into Ossetian, and elements adopted by those and others from the common local Japhetic substratum (KAMBOLOV T.T. 2006: 277).

Kambolov points out that determination of the direction of borrowing is possible using morphological, etymological, phonetic, and other criteria, but does not propose a criterion for the stratigraphy of matches. M. Dzhurtubaev does this sharply polemicizing with V.I. Abaev. He analyzes a huge amount of data on the mutual linguistic borrowings of the North Caucasian peoples and, in particular, on borrowings in the Ossetian language from the Turkic and other languages. He proves, by using numbers and facts, that Karachais and Balkars lived in the Caucasus long before the Ossetians came here (DZHURTUBAYEV M. 2010: 265-413). There is no possibility to stay on his arguments, it's a separate issue, but it should be pointed out that Dhurtubayev was wrong, believing that the Ossetians came to the Caucasus not from the Great Steppe, but from the Transcaucasus. Like the Turks, they came from the steppes, but one and a half thousand years later.

Similarly, the Balkars and Karachais were pushed back to mountainous areas by the Kabardians and Circassians but the Kumyks continued to live in the plain, although at some time they too advanced to the valleys of Dagestan. This has been evidenced by the names of the Sulak and other rivers having the Turkic component of Koisu. Having settled near peoples of different origins, the Turks not only adopted the customs and lifestyle of the local population but also enriched the common cultural fund of the peoples of the Caucasus. For example, a wide custom of "milk brotherhood", based on the transfer for a time of a newborn child to another family originated from them. This custom is called emgek, emchek, but the same words can mean "milk-brother", or "foster brother". That the custom is of Turkic origin proves its name, which is based on the word that in the Turkic languages means "mother's breast" (Kum. ämcäk, Karach., Balk emček).

That the Cumans, never were in Central Asia is confirmed by the study of the genetic structure of the population of the Western Caucasus:

As for the Eastern Eurasian component in the studied populations, it was represented by about the same degree according to how mtDNA and Y-chromosome. In addition, Turkic-speaking Karachai don't demonstrate a substantial portion of this component which is true for mtDNA. Moreover, some populations of Abkhaz-Circassians contain it to a greater extent. Data on the Y-chromosome, generally confirm this result…(LITVINOV SERGEY SERGEEVICH, 2010, 20).

At left: Balkars (Karachais?). Photo from the site "Forgotten history."

As you can see in the photo at left, the Balkars and Karachais have no Mongoloid features. It is believed that the ancestors of these people were the Cumans, who allegedly came from behind the Volga River into the Black Sea steppes in the early 11th century forcing out the Pechenegs from there.

However, we have no historical evidence supporting this assumption, though the invasion of numerous people into the neighboring country could not be missed in ancient Russian and Byzantine sources. The Tale of Past Years first noted the Cumans under 1055 and it seems quite casually: "In the same year came Bolush with the Cumans and Vsevolod made peace with them, and the Cumans returned where they came from." There is nothing new about the presence of the Cumans in the immediate vicinity for the chronicler.

Before the arrival of the Turkic people in the Ciscaucasia, the carriers of Maikop culture of unknown ethnicity dwelled there, which can not be identified with any modern Caucasian people. Therefore, the assumptions can be different and one of them may be that the Maykopians were forced out by a separate branch of the Turks beyond the Volga and then migrated a little south of the bulk of the Turks in the direction of the Altai. The arrival of migrants from Eastern Europe is associated with the appearance of Afanasiev culture in Asia, which could not develop on local soil:

In the archeology of South Siberia and Central Asia, Afanaiev's culture has long and rightly held a special place for many reasons. The most significant of them are the fundamental cultural transformations, which for the first time take place at this period on the indicated territory. The key components of the "Afanasiev phenomenon" were formulated by M.P. Gryaznov… This is a transition to the cattle-breeding type of economy, the beginning of the metallurgy of copper, several indirect data that testify to the process of the emergence of a complex system of social relations, involving the emergence of social stratification, special ideological ideas and other innovations that point to a completely new, recognizable matrix, which will finally form in the steppe world a little later (FRIBUS A.V., 2012: 199).

The Afanasiev culture sites are found in a wide space – on the Upper and Middle Yenisei Rivers, in the Altai Mountains, and in Mongolia. Their study was carried by various groups of researchers independently of each other without generalizing conclusions (STEPANOVA N.F., POLAKOV A.V. 2010: 4). However, anthropological studies show that craniological types of Afanasyevites do not differ from the skulls of Seredniy Stih and Pit people of the Zaporizhzhia region or Kalmykia, which are either descendants of Seredniy Stih people or a mixed group with a mixture of the same components as the population of the Seredniy Stih culture (SOLODOVNIKOV K.N. 2003). The archaeological data confirm this conclusion:

Many features that can be considered as ethnocultural, point to regions where the Proto-Afanasiev complex could form – these are the territories of the Lower Dnieper and the steppe Crimea up to the Azov Sea and Ciscaucasia. Only here are the analogies of the Afanasyev funeral rite, in particular, specific funerary structures. As for the rest of the elements of funeral practice, the whole set of attributes in the most general form would be more accurately compared with the early common Pit standard, which was an integrating element at the early stage of the forming of the ancient historical-cultural area (FRIBUS A.V., 2012: 200).

Thus, there are data that allow us to assume that Afanasiev culture was created by the Turks who came from the steppes of the Black Sea Northern shore and the Azov Sea. The chronological framework for the migration of Turks to Altai is difficult to establish. The similarity of the Afanasiev and Pit sites allows us to consider them synchronous, but there is a distance of several thousand kilometers between them, so a chronological shift is inevitable. On the other hand, the determination of the age of the Pit Cultural-Historical Community was calculated using the radiocarbon method, so there is no other way to use the same method to determine the age of Athanasiev culture. According to the calculations, the upper limit of the range of radiocarbon dates of funerary graves in the Middle Yenisei and Altai coincides with an accuracy of one year (2289 and 2290 BC). Altaic dates are evenly distributed over 1500 years, which contradicts the number of left sites, and in the Middle Altai are on a chronological segment of 700 years (3200-2500 BC). The question of why the Afanasiev sites could appear in the Altai earlier than in the Middle Yenisei is to be considered open (POLAKOV A.V. 2010: 161).

However, while agreeing that the creators of the Afanasiev culture came from the West, as evidenced, among other things, by the dissemination of wheeled vehicles (see the map below), one must agree that Afanasiev sites in the Middle Yenisei could not have appeared earlier than on Altai.

Spreading the cart transport in Ural-Kazakhstan Steps.

On materials of (I.V. Chechushkov, A.V. Yepimakhov, p. 207)

Turkic tribes that crossed the Volga began to settle on the territory of modern Kazakhstan and further to the east, following the order formed by the location of the settlement sites on the Urheimat. The Yakuts, having populated the extreme eastern area of the whole Turkic territory, so moved as the first northern of Lake Balkhash in the direction of Lake Baikal. Subsequently, they went up the Lena River to places of their present habitat. Following them, came the ancestors of the Tuva people, which we conventionally call Tuba. They reached the headwaters of the Yenisei and are living there now. The ancestors of their modern neighbors in the Altai Mountains were also neighbors in the Urheimat. The Khakasses, Kamasins, Shorts, and Chulym Tatars are residing north of them now. They all speak closely related languages derived from a paternal language, which we conventionally call Khakas, which area occupied the northern part of Turkish territory on the Urheimat. They moved as more northerly flow, and behind them moved their southern neighbors Kirghiz. At certain times they had to occupy neighboring territories in Siberia, but later the Kyrgyz moved to Central Asia, where they are dwelling now. In order of priority, the common ancestors of modern Kazakhs and Nogai moved after the Kyrgyz. The Kazakhs gradually colonized the large area from the Lower Volga to the Altai Mountains and the Nogai have recently returned to Europe. The last of the Turks, who crossed the Volga, moved ancestors of modern Uzbeks and Uighurs, which we call generalized Qarluqs (see map below).

Along the right bank of the Syr Darya River the Qarluqs reached the lower reaches of the Zarafshan River, where and in the near areas the Uzbeks dwell at present. The Uighurs populate the Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. They should not be confused with Sary Uighurs speaking a language similar to Khakass. They dwell in Gansu province in northern China, to the east of Xinjiang. By which way did get they there, hard to say but the way of the Qarluks can be restored by archaeological finds:

The moving of steppe tribes to the borders of Central Asia is evidenced by an open in the Low Zeravshan River burial place of Zamanbaba and other relics united now in a Zamanbaba culture” (MASSON V.M., MERPERT N.Ya., 1982: 329).

The sites of Zamanbaba culture, found currently in the region of Khwarezm, near Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara, are close to Andronovo culture on several features. At the same time, its funeral ceremony has features of the Catacomb culture. All this gives reason to believe that steppe tribes of Pit shape participated in its formation (MASSON V.M., 1989: 64)

Presumably the moving of Turks southward to Afghanistan was stopped by numerous local populations. Fortified settlements in Margiana with traces of fire and found there pottery of steppe appearance can confirm this assumption. After the first meetings with the militant nomads, local farmers began to build fortifications to protect their settlements and temples. The first appearance of regular fortresses in the south of Central Asia dates back abroad III – II mill. BC. (SHCHETENKO A.Ya. 2005, 124-131). This time corresponds exactly to the continued migration of Turks in the steppes of Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

Turkic expansion to the east continued for several centuries and at the beginning of the Bronze Age, a new wave of Turks advanced to the Altai, becoming the creators of the Andronovo culture and their European morphological features can be confirmed by data of anthropological research:

Caucasoid in their morphological features population was in the vast majority of the people of the Altai-Sayan highlands in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, partly in the early Iron Age. Mongoloid admixture is fixed at this time only in isolated cases but has steadily increased since the Early Iron Age reaching full superiority in modern times (ALEKSEYEV V.P. 1989: 417).

Morphological similarity of a portion of Caucasoid skulls of the Andronov series from the burial place Preobrazhenka-3 with series of Bronze Age steppe cultures suggests the possibility of the migration of population from the western regions of the Andronov culture, which physical appearance manifested Mediterranean racial type (MOLODIN V.I., CHIKISHEVA T.A. 1988: 204).

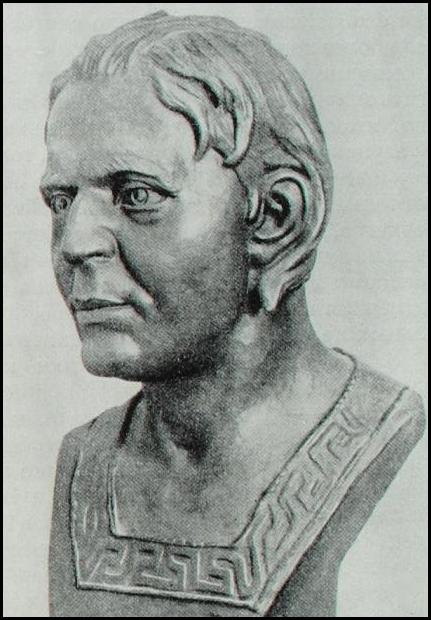

At right: A man from Bronze Age. Kazakhstan and Southern Siberia. Andronovo culture.

The reconstruction of M.M. Gerasimov.

(Vsemirnaya istoriya v 12 tomakh. 1955. V. 1, p. 457).

It also draws attention to the fact that "at the Andronov time the population of Baraba steppe was differed by exceptional heterogeneity" (Ibid: 204), but the people of Caucasoid appearance are specifically linked by experts to the migration of the Indo-Europeans to Siberia and Central Asia:

The origin of the Andronov community is one of the central issues in the history of Indo-European peoples. Indo-Iranian or Iranian ethnicity of this community is proved definitively (KOZINTSEV A.G., 2009, 126).

How fair and on what basis this bold assertion is used can be inferred from the following fact:

In 1960, archeologist S.S. Chernikov published in Moscow an interesting book "East Kazakhstan in the Bronze Age", in which, based on the archaeological material he had extracted, he expressed "seditious" thoughts: carriers of Andronovo culture, which were considered Iranian-speaking, were rightly called by him as the ancestors of the Turkic peoples. Some archeologists, captured by the idea of the Iranian-speaking Andronovites, immediately attacked S.S. Chernikov with harsh criticism. (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 6).

The question arises to the staunch supporters of this view: How could it happen that a large mass of Indo-Europeans completely disappeared from the face of the earth, even without leaving visible traces in the languages of the local population? Even if they were gradually dissolved therein, then, as the experience of the Tochars shows, it should have gone for hundreds of years. During this time, immigrants from Europe had to assimilate at least a part of the local population and impose their language, since they were the bearers of a higher culture than the inhabitants of Siberia. That's what we just see if the migrants will be recognized as the Turks. During the subsequent cross-breeding of the Turks with the local population as a result of co-existence together, a uniform anthropological type was arisen with obvious Mongoloid features of many ethnic groups, either kept their Turkic (Yakuts, Tuva, Khakas, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, etc.), or Mongolic language.

Anything definite about the migrations of the ancestors of the Bashkirs, Uzbeks, and other people is hard to say because their Mongoloid element is expressed enough clearly. What places and at what time were been settled by these people, remains to be seen.

See also

The migration of the Indo-European Peoples

at the End of the 2nd and at the beginning of the 1st Mill BC

The Expansion of the Finno-Ugric Peoples

The Slavic Expansion