Scythian Mythology

Talk about Scythian mythology should begin with the fact that before the emergence of the Scythians in the steppes of Ukraine, the Trypillian and Pit cultures existed in this region in the 3rd mill. BC. The question of the ethnicity of Trypillian culture is controversial. Still, the creators of Pit culture were the Turkic tribes (see section Ethnicity of the Neolithic and Eneolithic cultures of Eastern Europe). I associate with the Scythians the Turkic tribe of the Proto-Chuvashes, and the Chuvash language has preserved the most archaic features of the Proto-Turkic language (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998, 65-66, STETSYUK V.M. 1999, 85-95). Studying the Scythian mythology, one can not lose sight of the cultural continuity that could stretch for millennia.

There is extensive literature devoted to Scythian mythology in the world, however, most researchers initially erroneously refer the Scythians to Iranian people, and then selectively adopt more or less pertinent facts to explain the meaning of the names of gods, myths, and legends or scenes depicted on the Scythian vases and so on. The limited nature of such an approach was not without attention and in fact, became a subject of considerable criticism:

Attempts to reconstruct the "Scythian model of the world" were made in Scythology. However, from our point of view, they were not comprehensive because the reconstruction was carried out on an Indo-Iranian linguistic and mythological basis, the possibilities of which, as already mentioned, are limited for the interpretation of Scythian myths (HASANOV ZAUR. 2002: 354).

The author of these lines undertook a serious attempt to reconstruct the "Scythian model of the religious and mythological system of the world based on Turkic languages" (ibid: 303-358). This attempt causes great confidence, but it remains incomprehensible why the Chuvash mythology and the Chuvash language were completely ignored in the study. Chuvash is the only language among all Turkic that has retained the features of the paternal Turkic language. Accordingly, Chuvash mythology must preserve the archaic worldview of the ancient Turks. The model presented by Hasanov would be more perfect when referring to the spiritual heritage of the Chuvashes. In this essay, we will try to eliminate this shortcoming in our approach to studying the mythology of the Scythians.

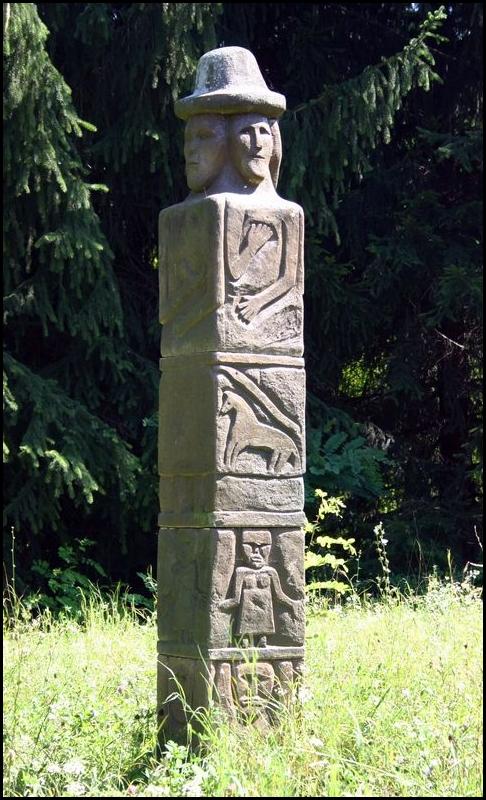

Many linguistic and archaeological pieces of evidence convince us that the Scythians were the Turkic tribe of Protochuvashes. The same is confirmed also by Scythian mythology. By identifying the Proto-Chuvashes with the Scythians, we get a satisfactory explanation for the significant fact of the absence of fire, the wheel, and the chariot in Scythian worship, which are so characteristic of Iranian people. At the same time, Scythian mythology has an acceptable explanation for deciphering the names of Scythian gods using the Chuvash language. Scythian monuments of culture have a certain reflection of the Chuvash beliefs and customs. However, some are considered not Scythian, such as the mysterious stone idol (see the photo at left).

The totem pole found in the Zbruch River, the left tributary of the Dniester, in 1848, was traditionally considered a Slavic monument, however, some scientists believe it has no analogies in Slavic mythology and reveals a great similarity with Scythian stone sculptures. This case gives grounds to look for clues of this carved image in Scythian mythology.

According to Herodotus, the Scythian cult did not know the images of gods, but M. Rostovtsev observed a contradiction of these words with facts. He noted the presence of the image of the Scythian gods, which were made for the Scythians by the Greeks. However, ignoring anthropomorphic stone sculptures in the steppes, he explained this fact as if they allegedly resulted in the Hellenization of the Iranian population in the steppes at a later period (ROSTOVTSEV M.I. 2002: 55).

D. Rayewski argues that the Scythians borrowed human images from ancient oriental and Ionian traditions. He examines the evolution of sculptures and comes to the conclusion that they reflect the way of modeling the universe, pointing out that some researchers give them mythological interpretations (RAYEVSKIY D. 2006: 246-254)/

At right: Steppe stone sculpture. The park-museum of the stone "babas" (Luhansk, a city in eastern Ukraine).

In 2011, a granite pillar was found in the village of Ruchaivka in the Zaporizhzhia Region. As it turned out after investigation this is a Scythian anthropomorphic stele (see. photo below).

Left: Stella from Ruchaivka, front side

. Photo from the magazine "Archeologia" (OSTAPENKO M.A., PANCHENKO I.V. 2014. 2014, 61. Fig. 2)

According to the description of the figures, they refer to an anthropomorphic pillar variety. There are two circles, obviously protective plates, on the breast of the figure representing a man. The man holds a massive rhyton in his right hand. One sees a belt with buckle-clasp, on which hang an acinaces (short sword) and a quiver. The hands of the man are bent at the elbows, and, as it usually happens in such figures and tombs, the right hand is pressed to his chest, and the left goes to the stomach (compare with the Zbruch idol and the photo below). The enigmatic meaning of the hand position does not yet have an explanation, but it has been practiced in the graves for thousands of years.

In 1992, an expedition of the Association of Lion (Lviv) excavated under the direction of a Ph.D. V.S. Artyukh, a human burial with the same hand position on a Trypillian site near the village of Moshanets of Kelmentsi district in the Chernivtsi Region. The Scythians-Chuvashes adopted this ritual from the Trypillians when they dwelled nearby. Ukrainian archaeologists, describing in detail the sculpture of Ruchaivka, made the following generalization:

It seems, that in archaic times, these monuments became a dominant symbol of the "world tree" or the phallus, which had anthropomorphic traits. Later, they become more and more humanoid in form with a gradual transition to the anatomic sculptural plasticity and, possibly, to the personalization of an image (ibid, 63).

The human burial from the Trypillian site near the village of Moshanets.

Photo of Valentyn Stetsyuk.

First let us start ab ovo and consider Herodotus' legend about the origin of the Scythians. According to this legend, the first man in the once desolate country, was Targitaios (Ταργιτάον), the son of Zeus and the daughter of the Borysthenes River (HERODOTUS, 1993: IV, 5). The first partial word of the name has such correspondences in the Turkic languages: Old Turkic täŋri 1. "heaven", 2. "god", Balk., Karach. tejri, Tur. tanri, Chuv. tură, Yakut. taŋara etc "god". Having taken into consideration Old Turkic toj "feast", Balk., Karach. toj, Tat., Chuv. tuj "wedding" the name Targitaios can be explained as "the wedding of gods”. This wedding can be referred to the known mythology category of "the sacred marriages" of old ancestors (LEVINTON G.A. 1991: 422-423). Targitaios had three sons: Lipoxaïs (Λιπόξαϊν), Arpoxaïs (Ἀρπόξαϊν) and Colaxaïs (Κολάξαιν). V. Abayev, who is considered to be a great authority in Scythian question, asserted that the second part of these names is -ksay and explained it as "a king-ruler" (Av *xayaš "to shine"). Therefore he gave for Colaksay such etymology: *Xola-xayaša "Sun-king" (ABAYEV V.I. 1965: 35). The first part of the restored name is questionable in the absence of Iran *xola, though words xor/xur "a sun" are present in some Iranian languages. However V. Abaev considered the transition r → l untypical for the Iranian languages and searched for its explanations (Ibid: 36) but later in another paper, he nevertheless acknowledged that "the first part is not clear" (ABAYEV V. I., 1979: 310). A.K. Shaposhnikov asserts that this name is not Indo-Iranian (SHAPOSHNIKOV A.K., 2005: 41). Two other names have been usually explained without details as Mountain-king and Depth-king – that allow seeing the connection of all names with the elements of the universe as the Upper, Middle and Lower Worlds (DUDKO D.M., 1988: 66).

Another interpretation of all three names can be given using the Chuvash language. First of all, Turk. arpa "barley" (Chuv. urpa) attracts attention, further, the typically Turkic say which, as well as ksay, can be the second part of all three names. In that case, these names can be divided into two parts: Arpak-say, Colak-say and Lipok-say. Chuv. săy "dish, course" together with arpa suits the explanation of Targitaios name as no wedding goes without a banquet. Thus, Arpaxais means "the dish of barley”. The epenthetic sound k appeared in this word obviously due to the similarity to two other names and for easy articulation.

Three courses for Targitaios' wedding

According to the sense of the word arpa, also kolak and lipok also should mean some food. Chuv. kayăk "bird" instead of kolak can be taken according to the sense as Chuv. a – corresponding Old Turc. o, and Chuv. ă in Old Turk. a (RONA-TAS A. -1, 1987-1: 47). The only objection is the discrepancy l → y. Old Turk. l was kept in the Chuvash language therefore this transition is not natural here but in principle, it often takes place in other languages (in particular, in Hungarian, ly is pronounced as y). On the other hand, it is semantically close – Chuv. kălăk "brood-hen", which increases the likelihood of explanation of Colaxais as "dish of bird". As for the name Lipoxais, probably, it was somewhat distorted by Herodotus or his informant. Maybe, Lipoxais should sound like Paliksais then the first part of the name could well correspond to Turk. balyk "fish" (modern-day Chuv. pulă). Hence, in the wedding of gods, three dishes would have been sent – the course of bird, barley, and fish. The first dish could correspond to the Scythian’s imagination of the "Upper World", the second dish would be referred to as the "Middle World", and the third one goes to the "Low World". Such personification of the elements of the universe corresponds better to the proposed idea of the mountain as "the middle world" which can be accepted hardly. The mountain approach to the "Upper World" concept is more likely.

The Trinomial model of the universe was adopted by the Proto-Chuvashess from Trypillians who divide the world into three planes, an underground, ground, and celestial sphere. This is evidenced by ornamental compositions on Tripoli culture monuments, referring to the Chalcolithic period [ZALIZNIAK L.L. (Ed). 2005, 125]. Chuvash folk cosmogony also represents the world in the form of three tiers, but aboveground, and the Earth itself is square. This representation generally corresponds to the Zbruch idol, which we speak of. And, as it turns out, the Chuvashes still represent ancient beliefs in the form of round and quadrangular totem poles. The album with pictures of sculptures of the ethnocultural park "Suvar" in the city of Cheboksary (Chuvashia) demonstrates this. Among the several dozen wooden figures, we can find some of them have a resemblance to the Zbruch idol (see photos above). Note the typical position of the hands of the left figure. But in general, we have reason to assume that the erection of the Chuvash totem poles in ancient times had the same purpose as the anthropomorphic sculptures of the Scythians, which were "one of the objective embodiments of the cosmic pillar – the imagination of the world order" (RAYEVSKIY D. 2006: 251).

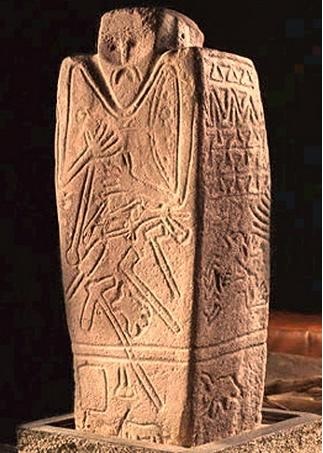

In 1973, a stone idol was found in the village of Kernosivka in the Novomoskovsk district of Dnepropetrovsk Region, which dates back to the end of the III – beginning of the II millennium BC. It has a quadrangular form just like the Zbruch idol. Images on the idol give a certain idea about the material and spiritual culture of the population of the Black Sea steppes of that time and its connection with Trypillian culture.

At left: The idol of Kernosivka. Historical Museum named after Dmitro Yavornytsky. Photo from the site Ukrainian antiquities

On the central part of the idol there is a hunting scene and three axes of various types are depicted. Above the girdle of the idol, the pattern resembles a turtle. In the lower part of the idol, there is a phallus, and below it are two horses. On the left side of the idol is an ornament, and under it, two people seem to dance. Still, lower is the figure of a bull. On the back, there is the Tree of Life. In addition, there are images of tools of a blacksmith or metallurgist.

The legend about the origin of the Scythians tells that during the reign of the sons of Targitai, a golden plow, yoke, ax, and bowl fell to the ground, which went to the youngest Kolaksai, and with them the entire Scythian kingdom.

It is logical to assume that these objects were intended to be in the sky before falling from the sky. Corresponding words related to these objects are absent among the astronomical names of the Indo-European peoples presently. In this regard, it is not possible to interpret the event through Indo-European languages. A plausible interpretation was suggested by M.Ch. Jurtubayev. He connects a plow with the constellation Ursa Major, which in the Karachai-Balkar language is called Myryt dzhulduzla "Constellation of Ploughshare" (Kar., Balk. myryt "plowshare"). The constellation of Libra is called by the Karachay-Balkarians Boyunskha yunsa dzulduzla, while the Kar., Balk. bojunskha is "yoke". The constellation North Crown resembles a cup and is called by Karachay-Balkar Chemyuch julduzla (Kar., Balk. chemyuch "cup") (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 44). The correspondence to the ax is seen by Jurtubayev in the name of the constellation Orion Guide dzhulduzl, but a suitable word in Karachai-Balkar language was not found.

The Chuvash called an ancient plow akapuç and this word is present in the dialectal name of Ursa Major (Akapuç çăltăpĕ). The analogy with the Karachai-Balkarian name is obvious, and the similarity of the constellation to the plow is obvious too (compare the photo of the Big Dipper on the right). Generally, the interpretation of the legend with the help of the Turkic languages is convincing, but how Balkars and Karachais were connected with the Scythians is yet to be formulated. There are also many Chuvash-Balkarian lexical convergences mentioned Bolgaro-Balkarian (MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 305). The Balkarians were neighbors of the Proto-Chuvashes during the Khazar Khaganate and could have borrowed the names of the constellations from them.

At left: Goddess Tabiti (Ταβιτί) with a mirror in her hand . Gold plaque from Chertomlyk mound.

Using the Chuvash vocabulary, we can explain the names of all Scythian gods mentioned by Herodotus. The Chuvash pantheon as an integral part of the common Turkic formed independently of the Greek, but Herodotus tries to find a similarity between the Scythian and Greek gods. The most worshipped goddess at the Scythians was Tabiti, who corresponds to chaste Greek Hestia, the goddess of a home. On this occasion, M. Rostovtsev said:

At first glance, it seems strange to find in the Iranian pantheon a goddess with the non-Iranian name Tabiti occupying the highest place, while the supreme god takes only the second place (ROSTOVTZEFF M. 1922, 107).

M. Rostovtsev gave his explanation to this fact, which apparently did not satisfy V. Abaev, and he, looking for parallels between the Scythian and Ossetian mythologies, sees a correspondence between Hestia and Tabiti in the Ossetian deity of the hearth and chain of fire named Safa. His presentation of making the chain to the people is especially accentuated (A. ABAYEV V.I. 1979, 10).

As you can see, the similarities between the male deity and the goddess Tabiti are quite far, and even Safa's name has no interpretation in the Ossetian language. Apparently, over time, Abaev understood the far-fetched nature of his interpretation and found an explanation for the name Tabiti, i.e., supposedly Ir tapayati "warmer" (HASANOV ZAUR. 2002: 93). However, the meaning of the name is too prosaic and does not say anything about the particularity of the goddess. On the contrary, her chastity is reflected in the Chuvash expression tupa tu "to give an oath", which may mean "she who gave the vow of celibacy". To this day, the Chuvash have the custom of saying "tupa tu" (to give the oath of allegiance during the marriage), and Karachay-Balkar womenswear "Tobady!" (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 43).

Dmitry Rajewsk mentions Herodotus' words about especially sacred oaths of the Scythians (τάς βασιλτηίας ίστίαζ) as oats for "Royal Hestias", this is the oats for Tabiti (RAYEVSKIY D. 2006, 65). He also explains the presence of a mirror in the hand of the goddess by the existence of a wedding ritual and other rituals associated with marriage, in which the mirror is present as an integral traditional attribute (ibid. 73). As you can see, the modern Chuvash tradition is directly linked to the custom of the Scythians.

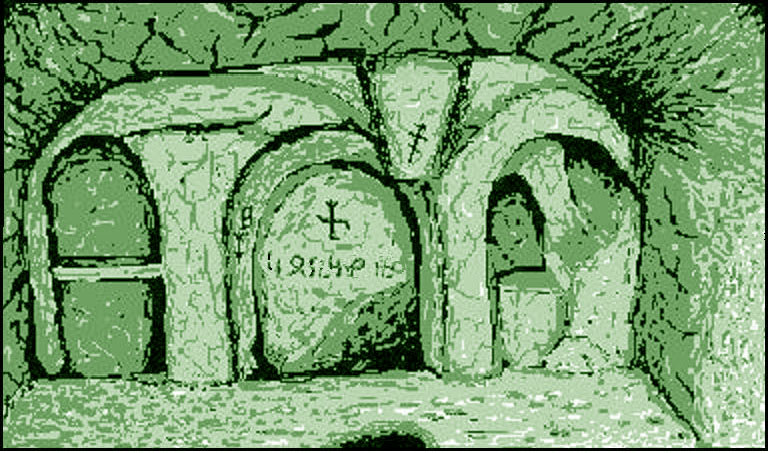

At right: The interior of a Proto-Chuvash cave sanctuary on the Dniester River near the village of Stinka. The sketch of the Valentyn Stetsyuk. 1989.

The inscription "tupa tu" is present on the altar of the Proto-Chuvash cave temple on the bank of the Dniester River. It was deciphered by the author with the help of one of the variants of Chuvash runic writing.

Greek Zeus and Gaia, by Herodotus, had Scythian matches Papaios (Παπαῖος) and Api (Ἀπί) whose names can be understood as "Grandfather" and "Grandmother", h.e. "Primogenitors", according to Chuv. papay "a grandfather" and Chuv. epi "a midwife". Similar words are in all Turkic languages, but the Chuvash words correspond to the Scythian gods to the greatest extent. The functions of the Greek god Apollo were various but he acted as an arrow-shooter or a destroyer most frequently (LOSEV A.F., 1991. MFW, Volume 1: 92-95). Herodotus connected him with Oitosyros in Scythian mythology, whose name could be understood as "who calls down trouble” (Chuv. ayta "to call" and šar "trouble"). The name of Scythian goddess Argimpasa (Ἀργίμπασα), which corresponded to the Greek goddess of fertility Aphrodite, is possible to explain as "the best daughter-in-law of the head of the family", taking into account Chuv. ar "husband, head of the family", kin "daughter-in-law", pakha "dear, valuable". By the certain presumption, it is possible to explain also the name of the Scythian god Thagimasadas (Θαγιμασάδας) which corresponds to Greek Poseidon, the god of seas and all water elements. In due time Poseidon, trying to ruin Odyssey, has broken his raft, therefore, Chuv. takana "a trough" (might be before "a boat" too) and šăt "to hole" can have interest in this case. The Balkarians and Karachais had a god of water, rain, and natural disasters Fuqmashaq (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 42).

At last, we shall talk about legendary Amazons. This name (from Gr. Αμαζων) is known us from Herodotus and means aggressive horsewoman.

According to the ancient Greek national etymology, it was clearly as α-μαζωσ "breastless" (μαζωσ Gr poetically "breast") as amazons, according to some Greek myth, had cut off the right breast themselves for better to shoot with a bow. The explanation is interesting but it doesn’t satisfy scientists.

Left: Hercules comes in fight with an Amazon. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Нью-Йорк, США)

Another explanation could be using Chuvash vocabulary. This mysterious name could have something similar to Chuv. çyn "a person, man". Taking into account Chuv. amă “a female, mother”, we find the explanation to the word the amazon – “the mother of people”. Chuvash scientists give a different explanation: amă "female beginning", çĕн – "warrior-winner" (Journal Life and Literature )

In the Chuvash national museum of local lore in the city of Cheboksary immediately at the entrance there is a statue of an Amazon woman (see the photo on the right). The explanation for this fact is that some of the customs of the Chuvash women are reminiscent of the way of life of the Amazons, and the elements of their traditional clothing are similar to combat armor.

Amazon woman from the Chuvash national museum of local lore. (Photo from the site Arts and crafts fair)

Herodotus explained the origin of Sauromatians from the marriage of the Amazons with Scythians and wrote:

…now the Amazons are called by the Scythians Oiorpata, which name means in the Hellenic tongue "slayers of men", for "a man" they call oior, and pata means "to slay"… (HERODOTUS, 1993: IV, 110-116).

Thus, Herodotus precisely specifies two Scythian words oyor and pata and gives their meaning. In the modern Chuvash language ăyăr means "stallion", and patak means "a stick". The first word could mean "a male, he-", therefore it could also mean "a man". The second word can be a derivative from not fixed Chuv. pata "to beat, kill". Mr. Fatih Şengül (Turkey) informed me that er, eyr or uri means “man, husband” and pata means “to kill, to hit” in Turkic. The same version is confirmed by Zaur Hasanov, saying that "this point of view has a place in Azerbaijani science", drawing on Turk. *ar "a husband" and bat, batyrmaq "to kill", "to die" (HASANOV ZAUR. 2002: 59).

Herodotus wrote that Scythians avoided borrowing customs of other folks including Hellenes, however in studying the beliefs of the Scythians, he absolutized the Greek pantheon of gods and tried to look for some matching to them at the Scythians. He could not pay attention to some Scythian beliefs, considering them "barbaric". However, the worship of the Tree of Life, which survived at Chuvash until now, has its roots in the Scythian times and even in the more ancient past:

… the original image of "Tree of Life"… can be found on plates of stone boxes or slabs overlapping graves, as well as on poles of burials of Pit (Yamna) culture (АLEKSEYEVA I.L. 1991: 22)

Symbol of the Tree of Life is the main element of the state symbols of the Chuvash – the emblem and flag. Its form with branches hanging down like the form of the Tree of Life on the amphora of Chortomlyk Scythian burial mound. However, a stylized Tree of Life is also present on the pottery of Chornolis culture which from Scythian culture was developed (see the section "Genesis of Scythian Culture"):

Among ornamented lugs (of Chornolis cups – VS), the earliest ones are decorated with motifs of the tree (KRUSHELNYTS'KA L.I. 1998, 165).

Left: Ornamentation of a cup lug of Chornolis culture (KRUSHELNYTS'KA L.I.. 1998, 158, Fig. 95, 30).

In center: The Scythian amphora from Chortomlyk burial mound. The Tree of Life on the vase is central.

Right: The shape of the tree of life in the Chuvash emblem and flag.

Larissa Krushelnits'ka believes that these motives tend to be a type of late Komariv culture (Ibid, 156). Continuity of Komariv (15-12 century BC.), Vysotska (11 – 7 century BC.), and Chornolis cultures she repeated in her writings.

Another main symbol of Chuvash folk art is the Signs of the Sun; such an ornament in the form of an eight-petal rosette or flower is called kĕskĕ. That it is he who “depicts the sun as the giver of life” wrote the famous expert on the Chuvash language and culture N.I. Ashmarin, referring to the words of the old Chuvash (TROFIMOV A.A. 1977: 64). Signs depicting the Sun on mirrors and other materials from burials near Olbia, Scythian Naples, and other places have been described by archaeologists (DRACHUK V.S. 1971: 222-229).

One of these signs is the swastika, and this sign was discovered in the mentioned cave sanctuary of the Proto-Chuvashes on the Dniester (see figure on the left)

Left: Swastika on the wall of the Proto-Chuvash cave sanctuary

From the above, it can be concluded that Scythian mythology is better deciphered using the Chuvash language and traditions. One can only wonder about the conservatism of the human mind when we find repeated statements that the Scythians were the ancestors of modern-day Ossetians.