The Indo-European Tribes.

After the clarifications have been made about the migration process of the speakers of the Nostratic languages, we will try to determine the new places of settlements of Indo-Europeans, Turks, and Finno-Ugrians in Eastern Europe. Let's start with the Indo-Europeans.

The abundance of works devoted to the origin of Indo-Europeans creates good opportunities for an arbitrary combination of the opinions of different scientists for the derivation of new theories with sophistic inferences that serve as the basis for further ethnogenetic exercises, which is clearly seen, for example, in one of the works on the origin of the Slavs (ALEKSAKHA A.G. 2013). Since linguists themselves cannot cope with the ethnogenesis of Indo-Europeans, archaeologists get down to business and, choosing as a basis one of the many assumptions about the origins of the first Indo-European cultures, then, solely using archeological data, without a shadow of a doubt, "reconstruct" a picture of the further cultural development of Indo-Europeans with an accurate indication of their path migrations and places of settlement, of which there are also good examples (ZALIZNIAK L.L. 2016). With the "knowledge of the matter" the state of modern Indo-European studies is characterized by one of the modern pundits as follows:

Indo-European linguistics has never been so well-documented as it is today. The precision of description and argumentation has never been so good. One must continue on this path and examine our linguistic past with ever greater precision and adequacy. Openness to new approaches is of great importance (MEIER-BRÜGGER MICHAEL, 2003: 15).

However, even though Indo-European linguistics is well documented, they still have no convincing solutions to the problems of Indo-European Urheimat. It seems that the Indo-European studies are given into the hands of bureaucrats who systematize all worthwhile for attention from their point of view and call to follow in this way further. "Openness to new approaches" is mentioned just for a good impression, because used in our studies the graphic-analytical method is described for a long time, and studies using it, were inserted in Academia.edu, but no mention of this new approach in above work. If Indo-European studies continue to remain closed to fresh ideas, then as a science it will stay indefinitely in limbo without a solid foundation of historical truth. Such a foundation is the reliable knowledge of the location of the Indo-European Urheimat and the space where individual Indo-European languages have arisen. The Urheimat of the Indo-Europeans as speakers of one of the Nostratic languages was determined to be in Transcaucasia (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 27-32). The division of their common paternal language should have taken place in a wider space. The localization of this space can be found using the graphic model of their relationship.

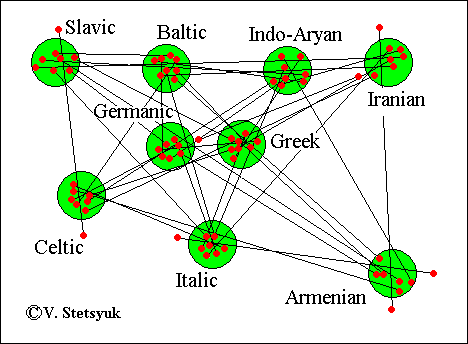

To construct the graphical model of the kinship of the Indo-European languages, was compiled a table-dictionary based on the etymological dictionary of J. Pokorny (POKORNY. J., 1949-1959 ). These data were supplemented with words from the etymological dictionaries of other Indo-European languages (FRAENKEL E.,1955-1965, FRISK H., 1970, HÜBSCHMANN HEINRICH., 1972, KLUGE FRIEDRICH, 1989, WALDE A., 1965. In total 2615 phono-semantic sets of the Slavic, Celtic, Baltic, Germanic, Italic, Greek, Indic (Indo-Aryan), Iranian, Tocharian A and B, Hittite-Luwian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian languages were placed into the table-dictionary. 489 sets were admitted as mutual words. The words with the matches found in seven from eight of the most represented languages (Germanic, Greek, Baltic, Indic, Italic, Slavic, Celtic, Iranian) were considered as the common Indo-European stock. Calculation of the mutual words in the language pairs gave the results that are presented in table 3.

| Language | Slav | Celt | Germ | Ital | Greek | Balt | Ind | Iran | Arm |

| Slavic | 732 | ||||||||

| Celtic | 307 | 751 | |||||||

| Germanic | 501 | 524 | 1202 | ||||||

| Italic | 279 | 368 | 518 | 792 | |||||

| Greek | 371 | 416 | 626 | 493 | 1159 | ||||

| Baltic | 530 | 358 | 652 | 359 | 542 | 1015 | |||

| Indo-Aryan | 235 | 275 | 455 | 335 | 511 | 394 | 865 | ||

| Iranian | 168 | 195 | 319 | 225 | 346 | 265 | 459 | 616 | |

| Armenian | 151 | 177 | 263 | 222 | 321 | 226 | 232 | 222 | 536 |

Table 3. Quantity of mutual words in pairs of the Indo-European languages.

The total number of words for each language is in the table's diagonal. The number of mutual words for each pair of languages can be found at the intersection of the corresponding column and line.

The data for Tocharian, Hittite-Luwian, Albanian, Thracian, and Phrygian are not presented in the table because of the small numbers. The localization of their sites in the relationship model of Indo-European languages will be analyzed later with the other methods. It should be taken into account that all the data presented here are current and are constantly being corrected while new terms are found, though these corrections don’t have much influence. The data oscillation of 5-7% does not modify the models at all, the correction results only in the more compact aggregate of points for language sites. The model of the Indo-European language relationships was built in consistency with the above-mentioned method and is presented in Figure 5.

Attempts to represent the relationships of Indo-European languages graphically have been made for a long time. One of the first to do so was H. Hirt (HIRT H. 1905. Fig. 2). His diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Hirt's diagram of the relationship between the Indo-European languages.

It is clear from the diagram that the German scientist assumed a step-by-step division of the Indo-European languages, which linguists later abandoned, without, however, not abandoning attempts to represent their family relationships graphically. Among others, the Polish scientist Lehr-Spławiński T. also proposed his diagram, taking into account a larger number of independent languages (LEHR-SPŁAWIŃSKI T. 1946.) Both Hirt and Lehr-Spławiński, when examining the relationships between languages, focused mainly not on vocabulary, but on grammar, however, in principle, all three diagrams are similar in their main features, especially the diagram obtained by the graphic-analytical method and the diagram of Lehr-Spławiński. True, the Polish linguist assumed closer connections between several languages and less close ones between others. Figure 23 shows his somewhat simplified diagram.

Fig. 23. Scheme of the relationship of Indo-European languages according to Lehr-Spławiński

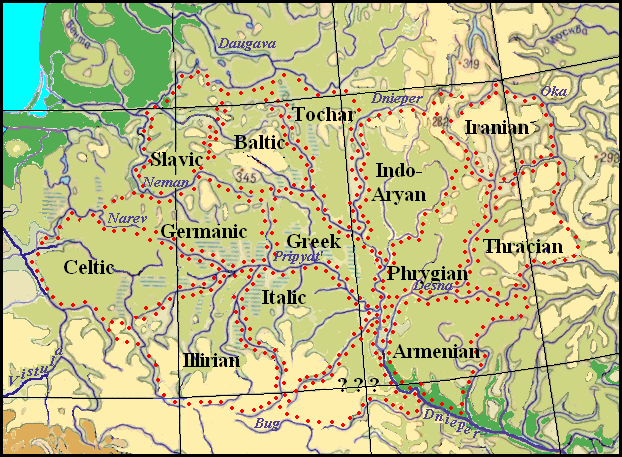

Now let us try to match the diagram obtained by the graphic-analytical method with some place on the geographical map of Eastern Europe. The areas of formation of languages absent from the diagram will be determined later and the Lera-Splavinsky diagram will be taken into account. When searching for a suitable place on the map, we will keep in mind that here the boundaries of settlement areas can only be rivers. The only satisfactory option for placing the diagram is in the basin of the middle and upper Dnieper and its tributaries, the Pripyat and Desna. Attempts to match the diagram with some other areas were unsuccessful. The areas of Indo-European settlements are shown in Figure 24.

Fig. 5. The graphical model of the Indo-European languages relationships.

One of these two reflexive variants was chosen to be able to place the Celtic area on the west, the Iranian site on the east, and the Baltic area on the north. The reason for this choice is evident. While trying to place the model on the map of Eastern Europe where rivers can be considered as the borders of habitats, we determined only one suitable variant in the basins of the Upper and Middle Dnieper and its tributaries the Pripyat’ and Desna. The map of the Indo-European space with separate areas for individual languages is presented in Figure 6.

Fig. 6. The map of the Indo-European habitats located according to the graphical model of relationships

We see that the Greek language, which is in the center of the diagram, began to form in the area between the lower Pripyat, Dnieper, and Berezina rivers. To the west of it, beyond the Sluch River (lt of the Pripyat) between the Neman, Narev, and Yaselda rivers, the Proto-Germanic language was formed. Further to the Bug or even to the Vistula was the area of the ancient Celts.

The Proto-Slavs dwelled north of the Germanic people on the right bank of the Neman River along the banks of the small rivers Merkis and Viliya. To the east from them to the Berezina River were the lands of the Balts. The Indo-Aryans inhabited the Sozh basin between the Dnieper and the Iput' River, and further in the area between the upper Desna and the upper Oka with the northern border along the Ugra River, the Irano-Aryans dwelled. In the Avesta), it is indicated that the Vakhvi-Datia River flowed in the ancestral home of the Iranians. It has long been associated with the ancient Oxus River, but the analysis of archaeological material and written sources gives grounds to identify Vakhvi-Datia with the Amu Darya River (KHOJAEVA N.D. 2013: 114-120). On the other hand, rivers containing the component wahvi "blessed, kind" in their names may be located in different parts of the territory inhabited by Iranian tribes at different times (A. STEBLINE-KAMENSKY I.M. 1999: 6.) In this case, the Vakhvi-Datia can be associated with the Oka River on the eastern border of the Iranian ancestral homeland that we have defined.

The habitats of the ancestors of the Armenians were in the area between the Dnieper, Desna, and Sula, and the ancient Italics – between Pripyat, Teterev, and Sluch. Such their placement explains the linguistic connections of Armenian and Latin with the Turkic languages (see Traces of Contacts between the Türks and Indo-Europeans in Vocabularies).

Between the distinct areas of the ancient Indo-Europeans, other possible settlement areas are visible (between the Berezina and the Dnieper, between the Desna and the Seim, between the Desna and the Iput, between the Bug and the Sluch (the Pripyat River). It can be assumed that in these areas the Protocharian, Proto-Phrygian, Proto-Thracian, Proto-Illyrian, and Proto-Albanian languages began to form since the entire Indo-European territory should have been continuous and compact without areas of languages of other origins wedging into it. Due to the same natural conditions, the entire area should have expanded gradually and evenly in different directions with the beginning of settlement from the primary area, and foreign-language newcomers would certainly have assimilated into the Indo-European environment. Based on this, the possibility of placing Indo-European languages in the "empty" areas was considered. (see The Areas of the Uprising of the Tocharian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian Languages.) After examining the connections of the Albanian and Thracian languages with other Imdo-European languages, it was concluded that both languages had to be formed in the same area, bordered by the Desna River and its left tributary, the Nerussa, in the west and north, and by the Seim and its right tributary, the Svapa, in the south and east. This gives grounds to consider the Albanian language a continuation of the Thracian language. Many researchers believed that the ancient area of the Tocharian settlements had to be located somewhere near the settlements of the Greeks, Balts, and Germans (KRAUZE V. 1959: 157; GORNUNG B.V. 1960, 25, 80; ABAYEV V.I. 1965: 3; GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984: 424), but more precisely, although not entirely, Porzig defined the area of the Tocharians:

Tocharian undoubtedly belongs to this group of languages (Germanic-Balto-Slavic – V.S.). It is characteristic that common phenomena unite the Tocharian language with the Baltic and Slavic languages, and at the same time, some of these phenomena connect all three languages with the West, and the other part – with the East. In addition, the Tocharian language has special connections with the Germanic languages and, at the same time, with Greek – connections that the Baltic and Slavic languages have no relation to… This determines the relative and absolute coordinates of the place of origin of the Tocharian language: it is located near the Germanic-Balto-Slavic space, in the area of rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea (PORZIG W. 1964, 315-316).

Therefore, there is every reason to place the area of the Tocharians between the Berezina and Dnieper rivers. There is very little lexical data to localize the area of formation of the Illyrian language, but taking into account other linguistic facts, Porzig finds reason to assert that, at least from early historical times, the Celtic and Illyrian language areas must have been adjacent to each otheк (PORZIG W. 1964 1964, 159). At the same time, he argued that "there are surprisingly few special connections between the Greek and Illyrian languages, although both of these languages, at least from the time of the migration of the Illyrians, constantly neighbored each other" (Ibid., 224). Taking into account these toponyms, the Illyrian area is located next to the Celtic area between the Western Bug and the upper reaches of the Goryn and Sluch.

Somewhere in the vicinity of the Greek and Armenian areas there must have been an area of primary formation of the Phrygian language, since there is sufficient evidence of its proximity to both Greek and Armenian. For example, Gamkrelidze and Ivanov believe: "The Phrygian language… exhibits structural features that bring it closer to the dialects of the Greco-Armenian area" (GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984: 910). According to Kapantsyan, Greek writers (Herodotus, Eudoxus, etc.) confidently speak of the kinship by origin and language of the Phrygians and Armenians as Phrygian emigrants. The Phrygism of the Armenians is also supported by the fact that the Armenians in the army of Xerxes stood under the same flag as the Phrygian one, and were dressed and armed similarly to them (KAPANTSIAN GR. 1956: 164). Moiseyeva speaks about the possibility of the genetic closeness of the Phrygian language to ancient Greek or Armenian (MOISEYEVA T.A. 1986: 13). At the same time, the area of formation of the Phrygian language should have been close to the Thracian one, since these two languages, according to the schemes of Hirth and Ler-Splavinsky, are also closely related. The latest studies allow us to speak about the place of the Phrygian language among the Indo-European languages more confidently. Having analyzed the obvious data on the phonetics and morphology of the Phrygian language, F. Kortlandt comes to the following conclusion:

… Greek, Phrygian, and Thraco-Armenian reflect a single Indo-European dialect area that was divided into two major isoglosses, namely the acquisition of guttural stops, which separated Phrygian from Greek, and the satemization of palatalized velars, which separated it from Thraco-Armenian. Phrygian is in some ways the missing link between Greek and Armenian (KORTLANDT FREDERIK. 2016: 6).

Under these conditions, the area between the Desna and Iput, south of the area of the Indo-Aryan language, is most suitable for the place of formation of the Phrygian language.

It is difficult to talk about the triangle between the Dnieper, Teterev and Ros. Its southern border is the Ros River, which is not difficult to cross and therefore opens the way for various newcomers from the Black Sea steppes. A permanent population couldn't survive here for a long time and this territory never played the role of an ethno-forming area in the future.

A careful examination of the entire Indo-European space gives grounds to single out another small area between the Dnieper and Ugra, lt Oka. It can be assumed that the formation of the Dardic proto-language took place here, which gave rise to daughter languages equally close to both Iranian and Indo-Aryan. If this assumption is correct, then there should be traces of language contact between the Dardic and Veps languages, since their areas were neighboring.

The Common Indo-European Space in Eastern Europe.

On Google My Maps, the border of the common Indo-European territory is marked with a red line. The area of the Greek language is shaded in burgundy, the area of Italian is red, Germanic is pink, Illyrian is light green, Celtic is yellow, Slavic is light yellow, Baltic is orange, Tocharian is brown, Indo-Aryan is dark green, Iranian is blue, Phrygian is violet, Thracian is light violet, and Armenian is light blue.

There is not much evidence to support the proposed location of the ancestral home of the Indo-European ethnic groups, but it does exist. Some of them were mentioned above. A significant argument may be the location of the ancestral home of the Slavs, which many scientists have been searching for. At the beginning of the 20th century, A.A. Shakhmatov, having examined the connections of the Slavic languages with other Indo-European and Finnish languages, concluded that "the original homeland of the Slavs should be considered in the basins of the western Dvina and the lower reaches of the Neman" (SHAKHMATOVЪ A.A. 1911: 707). An interesting study was made by V.T. Kolomiets. Having analyzed the original Slavic and borrowed names of fish in the Slavic languages and taking into account the rivers in which rarer species are found, she determined the Slavic ancestral homeland as follows:

… the Proto-Slavs occupied a relatively small territory to the west of the Berezina, to the south of the Western Dvina, to the east of the Neman, and to the north of the middle and lower reaches of the Pripyat (KOLOMIETS V.T. 1983: 140-141).

As we can see, the territory of the ancestral homeland of the Slavs determined by V. T. Kolomiets is located next to the area determined graphically and is larger. Perhaps this is the territory of later settlements of the Slavs. The territory of even later settlements was determined by the Polish botanist K. Moszyński, who also studied the names of trees in Slavic languages, and it largely coincides with the Indo-European (MOSZYŃSKI KAZIMIERZ. 1957). Such a coincidence confirms the assumption of the existence of ethno-forming areas in the basin of the middle and upper Dnieper.

Regarding confirmation of the location of the ancestral homeland of the Balts, the following opinion can be taken into account:

In Europe we now find the most archaic of the existing Indo-European languages – Lithuanian. This is explained by the fact that Lithuanian developed within the framework of its rather ancient homeland (or not far from it) and was influenced only by the closest related languages – Slavic and Germanic and only to a very small extent – Finno-Ugric. This fact is important in determining the ancestral homeland of the Indo-European languages (GEORGIEV Vl. 1958: 247).

Since the speakers of the Lithuanian language have always remained close to their ancient homeland and now inhabit lands partially located exactly where we have determined the ancestral homeland of the Balts, this is additional evidence in favor of the definition made.

The telmographic term is the name of swampy places. As is known, the upper reaches of the Pripyat are very swampy. There are confirmations in hydronymics for some other Indo-European areas too.

J. P. Mallory reduced the many hypotheses regarding the Indo-European homeland to four main models, which in turn have many variants. He did not find any of the models satisfactory, so this is not the place to consider them, but it can be mentioned that one of them is the closest to the one determined here using the graphoanalytical method. We are talking about the Baltic-Black Sea (+ Caspian) region. In assessing this hypothesis, Mallory writes, among other things:

The time depth of this hypothesis is usually associated with the Mesolithic. It is therefore difficult to understand how the populations from the Baltic to the Black (or Caspian) Seas could have had a common vocabulary at that time for domestic plants, animals, and terms related to late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age technology, such as for wheeled transport. Nor is it more likely that these words were borrowed (without any effect on their appearance) thousands of years later.

From an archaeological point of view, the territory of the ancestral homeland is an artificial construct and consists of at least two distinct cultural areas, beginning with the Mesolithic era. In other words, there are no cultural-historical grounds for assuming the use of a single language by the Mesolithic population from the Baltic to the Caspian Sea. There are also no grounds to speak of a contact zone in this area, a similar physical type, or any other phenomena that would allow us to conclude that a linguistic community existed. (MALLORY J.P. 1997: 61-82)

Mallory repeats the mistake of many linguists, believing that the disintegration of the common Indo-European language occurred in the ancestral homeland of the Indo-Europeans, and says nothing about the possibility of the existence of two ancestral homes – one where the common parental language was formed and the other where it was divided into many primary dialects. But in general, he understands that there could not have been a common language on such a huge territory. As for archeology, he is right here, speaking about completely different cultural areas and these areas correspond to two different language communities. We will see this when we find territories of settlements for the Finno-Ugrians and Turks as well.

The Indo-European languages are divided into two general branches which are named the Satem and the Centum. The Hittite-Luwian, Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Greek, and Tocharian languages belong to the Centum-group. The Slavic, Baltic, Indic, Iranian, Armenian, and Albanian as the offspring of Thracian languages belong to the Satem group. Excepting Slavic and Baltic, all Centum languages are located to the west of the Dniepr, and all Satem languages are located to the east of the Dniepr. The transformation of the Indo-European palatal stops k’ , g’, and gh’ into fricative s, s’ or affricates took place under the influence of Finno-Ugric languages which had a great set of fricatives. The Dnepr was the effective barrier for these influences if we suppose that this transformation in the Slavic and Baltiс languages took place later after the speakers of these languages came in direct contact with Finno-Ugric languages crossing the Dnepr.

Since the Indo-Aryan and Irano-Aryan proto-languages were formed in two distinct areas, there is no way to talk about the existence of a special Indo-Iranian linguistic community of the Aryans. This erroneous idea gives rise to many questions that will not be answered if we do not recognize the results we obtained using the graphic-analytical method. Until now, there are theories of the autochthonity of the Aryans in the modern places of residence of their descendants and, accordingly, there are variants of the migration paths of their ancestors, even though their ancestral homeland seems to be conjectural. Attempts by individual linguists to convince supporters of the idea of the Indo-Iranian community and the autochthonists using examples of the differences between Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages do not bring results, even though there are many of them and the number of such examples is growing, as works of recent years show (WITZEL MICHAEL. 2012).