On the Relationship of Nostratic and Caucasian Languages.

Abstract: The relationships between Nostratic and Caucasian languages are examined at the lexical level, following previous studies of the relationships between individual Nostratic, Abkhaz-Adyghe, and Nakh-Dagestani languages. In these studies, the graphoanalytical method, which is highly effective in examining the degree of relationship between languages within a single language family, was employed. Its application to studying relationships between language families is problematic. To test this possibility, a search for correspondences was conducted only between words in the lexical core, those that are mainly the most ancient in all languages. This work was initially made to examine the possible relationship of the Turkic and Mongolian languages, for which 140 words from the lexical core with correspondences in both families were selected. The same list was used to study the possible relationships between Nostratic and Caucasian languages. As it turned out, 51 matches from this list to Turkic or Indo-European languages, representing the Nostratic macrofamily, were found among the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages. More such matches were found for the Nakh-Dagestani family. Based on the previously established origin of the Nostratic, Abkhaz-Adyghe, and Nakh-Dagestani languages, it was concluded that all the languages of these families share a common genetic origin. In other words, there could not have been a distinct proto-language for either the Caucasian or Nostratic languages.

Keywords: Nostratic, Abkhaz-Adyghe, Nakh-Dagestanian, Kartvelian, graphoanalytical, “lexical core”, Caucasus.

The study of the relationship of large language families should begin with the origin of humans. According to the latest paleogenetic studies, it is recognized that the basic anatomy of Homo sapiens was present in Africa by at least 150 ka, though just 40 years ago it was possible to argue that Africa played no special role in human evolution [STRINGER CHRIS. 2007: 15]. The African fossil record shows that the settlement of Eurasia from Africa stretched over several tens of thousands of years, and the main route of human movement lay along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea:

The extension of early modern humans to the Levant by 100 ka has been confirmed by further dating analyses on the Skhul and Qafzeh material [Ibid: 15-16].

Thus, people from the Levant began to settle across Eurasia, during which ethnic groups and their languages were formed. Following the study of the Nostratic and Sino-Tibetan languages using the graphoanalytical method, they have been formed in the same place, namely, in the area of three lakes: Sevan, Van, and Urmia [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 27-32; STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2023: 1-3]. Firstly, this territory was inhabited by people of the Mongoloid anthropological type; then, they were displaced by Europeans. When considering the question of the origin of human language, it was found that these two anthropological types had some common phonetics and a portion of common vocabulary [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2019]. Later, the languages of these two anthropological types developed in their own ways and formed two groups conventionally termed the Asian and European. Following the recognition of the Nostratic nature of the Turkic languages, they were included among the European languages, while the Mongolian languages, whose ancestral homeland was identified in the Amur River basin [STETSYUK VALENTIN. 2010: 5-8], were included among the Asian languages. Thus, a close genetic relationship between these two language families is excluded; therefore, in this work, the common part of their vocabulary is considered the result of later mutual borrowings and is not taken into account. However, they are descended from a single original human language, from which all modern languages have developed over the millennia.

It is known that the Mongolian languages are not part of the Nostratic macrofamily, which typically includes Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic, Afro-Asiatic, and Dravidian languages. On the other hand, some linguists deny the existence of such a macrofamily, while others believe its composition should be expanded:

>br>The boundaries for the Nostratian world of languages cannot yet be determined, but the area is enormous and includes such widely divergent races that one becomes almost dizzy at the thought [BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2018: 4].

In particular, according to A. Dolgopolsky, Chukchi-Kamchatkan, and Eskimo-Aleut languages can be classified as Nostratic. Later, this idea was supported by Joseph Greenberg, and Bomhard suggested a kinship with Nostratic also of the Sumerian language(Ibid: 5-7). In addition to these languages, he also refers to the Nostratic languages as Tyrrhenian, Gilyak (Nivkh), and Yukaghir [BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2014/2015: 20].

Ultimately, everything comes down to the question of the possibility of monogenesis of all the languages of the world. At one time, one suggested that the idea of restoring a primary language by comparing existing languages is a chimera [YAKUSHIN B.V. 1985:66]. However, everything depends on the comparison methodology, which may be different. The very process of comparing the sound composition of words of distinct languages of a certain semantic field will answer the question of the existence of patterns in the names of the same objects by different people. O. Melnychuk had the same idea [MELNYCHUK A.S. 1991: 28] when he wrote about the obtained data testifying to the unity of origin of all the languages of the world:

These data are a series of extensive phonetically correlative etymological complexes, which are regularly repeated in the languages of each family, with large bundles of interconnected elementary meanings and with a specific, still not noted complex system of structural variants of the root, the same for each etymological complex [MELNYCHUK A.S. 1991: 28]

Mr. Melnichuk was engaged in comparative linguistics, in which methods of glottochronology were developed. One of them was proposed by Maurice Swadesh [SWADESH M. 1960]. He assumed that a certain part of the basic vocabulary of all languages forms a lexical core and tried to find this core. Firstly, he compiled a list of 100 words, and later expanded it to 207 words. Using his latest version, I checked the possibility of a genetic relationship between the Mongolian and Turkic languages. In this work, I discovered that barely 140 words from the Swadesh list have good correspondences in all Turkic and Mongolic languages [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2024]. Swadesh included in the lexical core words that appeared in languages over a long time and spread very widely, so not all the words in it are the most ancient. The oldest words can only be those that appeared in languages when human economic activity was limited to hunting and gathering. Words that appeared in the Neolithic with the development of agriculture and the changes in thinking associated with it cannot be the most ancient. Studying the question of the origin of numerals in Nostratic languages, I established that the initial counting of people was limited to two units, and then followed the definition of «many» [STETSYUK VALENTYN]. Thus, numerals greater than two and abstract words with multiple meanings, such as “fruit”, “right”, “fight”, “play”, etc, should be excluded from the list.

Assuming that the more often a word is used in a language, the earlier it appeared in it, the scientists set themselves the task of constructing a mathematical model of changes in the dictionary and, based on this model, theoretically obtaining a relationship between the time of the word’s appearance and its rank in the frequency dictionary. They proposed an empirical formula that describes the probability of a word appearing at a given point in time. The key to this formula is a certain constant, which itself can change for different chronological sections and different languages, but the speed of language development in different periods can be very different, and we cannot have the slightest idea about these features now. The authors objectively assessed their method, noting that they only wanted to demonstrate its capabilities, because to calculate the constant it is necessary to have frequency dictionaries compiled according to a single method, and historical lexicography should have been developed to such an extent that it could provide the possibility of recording the moment of the appearance of a new word with an accuracy of at least up to a century. Nevertheless, they claimed:

There is a relationship between the frequency and the time of occurrence of the word in his language… Most of the words with a high frequency of use are ancient words, and vice versa – the lower the frequency of a word, the more likely that the word is newly created [ARAPOV M.V., HERZ M.M. 1974: 3].

W. Mańczak also paid attention to the frequency of word usage and claimed that the most frequently used words speak of the origin of the language. Recognizing that the Romanian language has the most words of Slavic origin, followed by Latin, Turkish, and Modern Greek, he said that both the living Romanian language and the texts written in this language still give the impression of being Romance, not Slavic. A similar phenomenon is observed in the Albanian language. R. Trautman presents the following data from G. Meyer regarding the composition of the vocabulary of the Albanian language: out of 5110 Albanian words, there are 1420 words of Romance origin, 540 of Slavic origin, 1180 of Turkish origin, 840 of Modern Greek origin, 400 of Indo-European origin, and 730 of unknown origin [TRAUTMAN REINHOLD. 1948]. Such a motley vocabulary prevents the establishment of family ties in the Albanian language, if one doesn’t pay attention that words of Indo-European origin are more frequently used.

In this regard, the lexical core of all languages should include only the most frequently used words, assuming that they were among the first to appear in human language. This should be kept in mind if we proceed from the fact that the most ancient words should include those that consisted of a combination of sounds that humans first learned to pronounce. The search for these sounds was carried out based on Heckel’s Principle “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”, and it was established that they were bilabile b, bh, p, ph, sonorant m, n and neutral vowels of the «schwa» type (ə) [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2019]. That not all words of the lexical core are a combination of these sounds can be explained by the fact that the first words constituted a category of general meaning and were eventually replaced by words of a more specific meaning with a different sound. The development of speech could also have made certain adjustments.

In the noted work, the comparison of etymological complexes having a general meaning was carried out for some European and Asian languages. The Turkic languages were included among European languages following the place of their formation in Eastern Europe, after results of research using the graphic-analytical method [STETSYUK VALENTYN, 1998: 48-52]. The inclusion of the Turkic languages in the Altai family is erroneous, as the idea of the first Turkic people Mongoloids. The Mongoloid features developed in part of the Turkic people after mixing with the aborigines of Asia, with whom they came into contact after migrating from Eastern Europe to Altai. Accordingly, the comparison of Asian languages in this work was conducted on the materials of the Sino-Tibetan and Altai languages without the Turkic. The lexical material was taken from the Global Lexicostatistical Database as well as from etymological and bilingual dictionaries. As a result of the work carried out, the following was established.

1. For the components of the semantic field “to be, to exist”, “to bear, to be born”, “to grow” and its extensions in Asian languages, the same phonostems ab-, ba-, pa- and their possible modifications are used as in European languages and also phonostems based on the nasal bilabial m, which in principle could have evolved from a bilabial estop b.

2. In Asian languages, the phonostems ma-, me- and their possible modifications prevail among the components of the semantic field: “prey”, “food”, “fat”, “tasty, sweet”, although to a lesser extent than in Indo-European languages, and among them there are also phonostems based on other bilabial ones.

3. Compared to European languages, Asian languages have many fewer components of the semantic field: “sign”, “call”, “name”, “find”, “think”, “look”, with phonostems based on bilabial consonants. Obviously, they do not prevail among the words of this field.

These results allow us to state that European and Asian languages originated from one common proto-language, and their traces can be found in them. The dispersal of speakers of this proto-language contributed to the formation of many languages of varying kinship. On this basis, linguists unite them into certain language families. At the same time, the question remains open whether these languages had a paternal ancestor or not. In addition, some language families are united into macrofamilies, the existence of which many linguists deny. Moreover, even those who agree with their existence argue about their composition. This applies to the so-called Nostratic and Caucasian languages. According to one theory, the Georgian language belongs to the Nostratic, and according to another, to the Caucasian, even termed Ibero-Caucasian. Quite recently, the Georgian-Circassian-Apkhazian Etymological Dictionary was published [CHUKHUA MERAB. 2019], the analysis of the materials of which, using the results of research conducted with the help of the graphoanalytical method, can help to clarify the relationship of these languages. Here, such an attempt is made.

Using this method, the kinship relations of the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages and the areas of their formation were determined. They turned out to be located near the area of the Kartvelian language, which is related to the Nostratic, determined by the same method [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2009]. They are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Areas of formation of the Abkhaz-Adyghen languages on the eastern coast of the Black Sea

Based on the above, it can be concluded that closely related languages should have many similar words in the lexical core. The number of such words reflects the degree of their relationship. The work in question contains one and a half thousand etymons with matches in the Kartvelian and Abkhaz-Adyghe languages. Among them, a search was conducted for 140 nests of words of the semantic field, similar in meaning to words of the same lexical core, used earlier to establish the relationship of the Mongolian and Turkic, Hungarian and Finnish languages. There were 120 such nests, forming mutual pairs of matches, which indicates a close genetic relationship between the Kartvelian and Abkhaz-Adyghe languages. For comparison, let us recall that 70 such pairs were found in Hungarian and Finnish, while only 19 such pairs were found in Turkic and Mongolian. At the same time, the speakers of Finnish and Hungarian dwelt at a great distance from each other for thousands of years, while the speakers of Kartvelian and Abkhaz-Adyghe languages remained close neighbors. An analysis of these 120 nests will show the relationship between the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages and the Nostratic languages. The data for this analysis is given below. In this case, the author’s terminology is used, who calls the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages Sindy.

In each nest, the first is the proto-form of the Kartvelian words, which is matched with the proto-forms of the Sindy words, and then, if possible, matches in the Nakh-Dagestanian, Turkic, and Indo-European languages. Of the Nostratic languages, only these two were chosen because the Proto-Kartvelians and Proto-Indo-Europeans were neighbors of the Proto-Turks in their ancestral homeland.

1. ALL – C.-Kartv. *-ʒa- “all/everyone/everything” – C.-Sind. *-ʒa “all/everyone/everything”.

2. BACK – C.-Kartv. *godna “backside” – C.-Sind. *gwǝdǝ “vulva”. In Dagestanian: Av. gwend, Akhv. gwandi “hole”.

3. BAD – C.-Kartv. *cud- “bad” – C.-Sind. *cwǝd-a- “pollution/dirtying”. In Dagestanian: Dido cud-i “dead” – C.-Trc. qadaǧan, qadaǧa, qadaǧ “prohibition” (Az, Turkm. qadaǧan, Uzb. katagan, Kum, Tur. dial. qadaǧa, Yak. khadaǧa, Khak. khadaǧ [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 1997: 82]. – PIE k̂ū̆dh “dirt” (Gr. κυθνόν “σπέρμα”, Lit. šúdas, Let. sūds “shit”, “muck”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 627]. The following examples, Pokorny mistakenly attributes to the roots gʷōu-, gʷū: OInd. gū-tha-ḥ, – “feces”, Avesta gū-ϑa- “dirt”, “feces”, Ger. Kot “shit”, OSlav. gadŭ “reptile” (disgusting animal); Lith. gė́da “shame, dishonor” [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 483-485]. The meaning "bad" in many languages is the word "left". The origin of the Kabardian sǝmǝge-i "left" is not clear. It is unlikely to be original [SHAGIROV A.K. 1977: 59]. It can be compared with the PIE seu̯i̯o- “left” (OInd. savyá-, Avesta haoya-, OSlav. šuja “left”).

4. BELLY – C.-Kartv. *ṗaγw- “belly” – C.-Sind. *bǝγ-a “waist” – C.-Trc. I. böksäk “lower body “, “waist”, “ass”, II. bügsäk “belly”, “female breast” [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 213-214] – IE: OE bǽc “back”, Ger. Bauch “belly”, Rus. puzo “belly”, Lith pùžas “potbellied ”, paugželis “ruffe” [FRAENKEL E. 1962-1965: 682].

5. BIG – C.-Kartv. *did- “big” – C.-Sind. *dǝd-a „very/too, totaly/entirelly” – C.-Trc. didin – “strain one’s strength”, “dare”, “resist” (Az, Turkm, Tur, Gag, Tuv. didin- , Alt. tidīn-, Yak. tetim-, Khak. tīdīn-) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1980: 218] – Lith. didis “big”, Let. diž “big”, “splendid”, “noble” [FRAENKEL E. 1962-1965: 93].

6. BLACK – C.-Kartv. *sew- “blackening; darkening” – C.-Sind. *wăs-a “dark; dark color”. In Dagestanian: Dido sasju, Khv, Hin. sas:u “dark, dark color”.

7. BLOW – C.-Kartv. *zwer- “wind blowing” – C.-Sind. źwă- “air, wind”

8. BONE – C.-Kartv. *qwil- “bone” – C.-Sind. *qwǝ- “bone”. In Dagestanian: Tab. ḳur-ab, Rut. qǝr-ǝb “bone”.

9. BREAST – C.-Kartv. *ḳoḳo- “breast/teat; breast/teat nipple” – C.-Sind. **ḳǝḳa “woman’s breast; breast/teat nipple”. In Dagestanian: Cham. *ḳuḳuŋ “breast/teat nipple”, Lezg. *ḳwenḳ “breast/teat nipple” – C.-Trc. *kükrek „breast“ (Turkm. *kükrek, Tat. *kükrǝk, Kum, K-Bal. *kökürek a.o. ). The root *stem kök, which is separated from *kökür (←kökürek), is present in other languages of the Altaic family [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 1997: 137].

10. BURN – C.-Kartv. *çw-“burning” – C.-Sind. *-çwa “burning”. In Dagestanian: Lak. çu, Arch. oç “fire”.

11. CHILD – C.-Kartv. *maç- “little child” – C.-Sind. *mač- “few/little, small”.

12. CLOUD – C.-Kartv. mar- “cloud” – C.-Sind. *măL-ǝ “ice”. Nakh. mil- “cold” and in Dagestanian: maƛ, cf. Av. marṭ ← *marƛ “hoar frost”.

13. COLD – C.-Kartv. *ciw- “cold” – C.-Sind. *cwǝ “cold”. C.-Nakh. *čiw- “coldest season”.

14. COME – C.-Kartv. *cal- “going/avoiding, going away” – C.-Sind. *ca- “walking”. In Dagestanian: Lak ač-i “going”, Av. ač-in-e “accompanying”.

15. CUT – C.-Kartv. *çret- “cutting” – C.-Sind. *ṗçăta- “cutting, lining, notching, slashing”. In Dagestanian: And. çeṭ-un-nu “carving/working” – C.-Trc. kert- “chop, cut” (Alt, Chuv, Gaz, Kaz, Khak, Kyr, Tur, Turkm. kert- a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S 1997: 54] – PIE (s)ker-4, (s)kerə-, (s)krē- “to cut” (Arm. kʿorem, Gr. κείρω, Lat. corium, OIr. scar(a)im, Norse skera, Lith. skìrti, Let. šḱir̃t a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 938-947].

16. DAY – C.-Kartv. *deγ-e “day” – C.-Sind. *dǝγ-ă “sun”. In the Nakh-Dagestanian languages: C.-Nakh *daγ-u „rain”, Dido γwed-e, Hin. γwede, Khvar. γwade, Hunz. wǝdǝ ← *γwǝdǝ “day, rain, star” – C.-Trc. da:g “mountain”, “forest”, “north”, “west” (Turkm, Az, Tur. dağ, Uzb. toĝ, Kaz, Tat, Kum. tau, Chuv. tu [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1980: 117-118] – PIE dhegh “burn” (OInd. dáhati, Avesta dažaiti, Lith. degù, OSlav. žegǫ, Alb. djek, Cymr. deifio “burn”), – PIE *dei-1, dei̯ə-, dī-, di̯ā- “to shine”, “day”, “ sun”, “God" [Ibid: 240-241] – Chech, Bats. de, Ing. di “day”.

17. DIE – C.-Kartv. *ḳwed- “dying, losing” – C.-Sind. *ḳwădǝ- “dying, losing”.

18. DIG – C.-Kartv. *bar- “spade; digging (with spade)” – Pr.-Sind. *mar- “digging (with spade)”, Hatt. mar- “digging (with spade), cutting”. In Dagestanian: Bud. bar, Lezg. per, Khin. ber “spade” – PIE bel-1 “to cut out, dig, hollow”?? (Arm. pelem “cave, ditch”, possibly also MIr. belach “cleft, pass, path” and Celtic *bolko-: Cymr. bwlch, Bret. boulc “cleft”) [Ibid: 967] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech biel, Ing. bel, Av, Andi bel, Kar. bele, Achv. beli, Bagv. bel, Tindi bel “shovel”.

19. DIRT – C.-Kartv. *txwar- “soiling/dirtying, getting dirty” – C.-Sind. *txwa- “getting dirty/dirtying”.

20. DOG – C.-Kartv. *kuc-ur- “dog; puppy” – C.-Sind. *kwǝʒ- “wolf”. In Dagestanian: Darg. kw:ač:-a, dial. k:uč:a, Lezg. dial. kw:ač:e “bitch, dog” – C.- Trc. güžük “puppy”, “dog” (Turkm. güžük, Gag. güčük, Alt. dial, Uzb, qučuq, Bash. küčük a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 1997: 92].

21. DRY – C.-Kartv. *bex- “dry” – C.–Sind. *băx- “dry; steam”. According to Chukhua, “unity of C.-Kartv. *bex- “dry”: C.-Sind. *băx- “dry; steam” archetypes according to structure and semantics is doubtless" [CUKHUA MERAB. 2019: 100].

22. EAR – C.-Kartv. *qur- “ear; sense of hearing; watching” – C.-Sind. *qwǝ- “sense of hearing, listening; hearing” – C.-Trc. *qulaq “ear”, “hearing” (Alt, Az, Cr.-Tat, K.Bal, Kaz, Kyr, Tur, Turkm, a.o. qulaq, Chuv khălkhă “ear”. It is assumed that the word comes from the unfixed verb "to listen" [VÁMBÉRY H. 1878: 99]. A similar isogloss exists in the Finno-Ugric languages: Fin. kuulla, Veps kulda, Udm. kylyly etc “to hear” from *kǖle or kule [HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 524] – The proposed PIE roots k̂leu-1, k̂leu̯ə-: k̂lū- “to hear” are controversial but must be distantly related (OInd. śr̥ṇṓti ←*k̂l̥-neu-, Arm. lu, Lat. inclutus, clueō, Gr. κλέ(ϝ)ω, OIr. cloth, cluas, OHG. Hlot-, Norse hljōð, Goth. hliuma, Cymr. clywed, Lith. klausaũ, paklusnùs, OSlav. slovo, Toch. A,B klā̆w- a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 605-607]. Cf. SAY.

23. EARTH – C.-Kartv. *msu- “a kind of soil/earth (without stones)” – C.-Sind. *nǝšw- “soil/earth, clay”. In Dagestanian: And. onš:-i, Akhv. uŋs:-i, Cham. uŋs://uns:-i “soil/earth”.

24. EYE – C.-Kartv. *bil- “eye” – C. –Sind. *blă- “eye” (Abkh. á-bla, Ab. la). In the Dagestanian languages: Av. ber, Lezg. wil, Udi pul, Khin. pil “eye” – C.-Trc. bil 1. “know“, 2. “understand “, 3. “respect“, 4. “can“, 5. “notice”, 6. “visit“, “seeing off“ a.o. [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 137-138], OT. bilig „prudence“ – PIE ŭel-1 ”to see“ (Gr. βλέπω “look, see”, Cymr. gweled “sehen”, Lat. voltus, vultus „facial expression, mien, appearance”, Goth. wlaiton “‘to look around for, to search”, wulþus “glory”, Norse Ullr ‘God’s name’, OE wuldor “glory”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 1136-1137].

25. FALL – C.-Kartv. *breg- “hitting/striking; falling down” – C.-Sind. *bgă- “falling down; breaking”.

26. FAT – C.-Kartv. *dung-ir “fat/plump/stout” – C.-Sind. *dǝng- ăl “swollen up/bloated, inflated/puffed up”. The Nakh correspondence is in Ing. ṭangăr “paunch, belly” – C.- Turk. doŋuz “swine” (Tur, Gag. domuz, Kaz, Nog. doŋyz, Kum. donguz, Tat. dungyz) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1980: 267-268].

27. FATHER – C.-Kartv. *mu- “father” – Pr.-Sind. *mu- “mother”, Hat. mu “mother”. In Dagestanian: Udi baba, Lak. buta, Lezg. buba, Hin. obu, Av. emen, Akhv, Bagv. ima “father”, Ag bab, Khvar. baba, Arch. bu-va, Chech, Udi. nana, Bagv. ima “mother” etc. Words beginning with the bilabial consonants b, bh, p, ph, m or nasal n to denote parents are the most ancient in all languages and talk of the unity of their origin [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2019]. They do not require additional proof of relationship.

28. FEAR – C.-Kartv. *šur- “fear/scare” – C.-Sind. *šwǝ- “fear/scare”, Dagestanian linguistic material can be brought in this case as well; cf. And. sir-u//sirdu “frightening/scaring” = C.-Trc. *qorq “to fear” (Gag, Kaz, Kum. Tur, Turkm, Uzb. dial. a.o. qorq, Chuv. khăra-) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2000: 77-79].

29. FEATHER – C.-Kartv. *qwa- “fur/single hair, feather” – C.-Sind. *qwǝ “wool, hair”.

30. FEW – C.-Kartv. *ḳn-in- “small amount/minor, few; making/becoming smaller/reduce/fewer/ decrease” – C.-Sind. *ḳan- “fragment/piece/shard of broken object; crumb”.

31. FIRE – C.-Kartv. *guz- “fire; igniting fire”, “burning” – P.-Sind. *guz- “fireplace, stove”. Hat. kuz-an “hearth”. Likely, Nakh ḳurz word contains the same root; cf. Vain. ḳurz “soot”, though a glottocclusive ḳ is unexpected – C.-Trc. qyz “heat, fire”, “to heat up”, “to become hot”, “to become heated” (Gag, Kaz, Kum. qyz, Tur. kız, Az, Turkm. gyz, Chuv. khĕr a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. 2000: 189] – PIE ker (ǝ)-3 “burn” (OInd. kūḍayāti ‘sengt’, Norse hyrr "fire", OHG herd ”stove”, Lith. kuriù, kùrti “heat”, related root krā-s- „fiery glow“, „embers“, from which partly “red”, partly “bright”, “beautiful”: OSlav. krasa “charm, beauty”, krasĭnŭ “red”, “beautiful”, “pleasant”, “dressed in white” [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 571-572]. Following Chuv. khĕr, the common Nostratic proto-form is *kuř (kurz).

32. FISH – C.-Kartv. *pac- “fish” – C.-Sind. *pca- “fish” – С.-Trc. balyq “fish” (Az. Bash, Kaz, Kyrg, Tur, Turkm, Yak. balyq a.o.) – PIE peisk-, pisk- “fish” (Lat. piscis, Gmc fisk-a: Goth. fisks, Norse fiskr, OHG, OE fisk, OIr. īasc (*peiskos), Pol. piskorz, Rus. piskárĭ) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 796]. The previously mentioned Nostratic consonant ř (rz) had a voiceless pair in the sound ĺ (lš), which over time in different languages could turn into l, š, ss, s. For exampleь OT yĺyq "warm, hot" received the following modifications: Tur. ılık, Chuv. ăšă, Uzb. issik, in other languages also ysyq "id" [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2018: 4].

33. FIVE – C.-Kartv. *xust- “five” – C.-Sind. *štxwǝ “five”.

34. FLOW – C.-Kartv. *txew- “shedding, flowing of fluid/liquid” – C.-Sind. *txwă- “shedding/flowing of fluid/liquid”.

35. FOG – C.-Kartv. *nisl- “fog/mist; snow” – C.-Sind. *ns-ǝ/*ms-ǝ “snow”. In Dagestanian: Av. ωansi “cloud; fog/mist”, Tab. ams//ams:a//ams:, Ag. amsar “cloud; cloudy”, Proto-Dido *mus: “fog/mist; thick fog/low cloud, smoke” – C.-Trc. bus"fog", "mist", "cloudy weather", "steam, "dew", "hoarfrost" (Tur. dial, Tyv. bus, Tur, Alt. dial, Kum pus, Tat. bǝs, Chuv. păs a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978. 277-278]. See ICE.

36. FOOT – C.-Kartv. *baʒw- “foot” – C.–Sind: *bʒă- “bottom/root, basis/foundation” – C.-Trc. bajak “foot”, “leg”, “thigh” (Cr.-Tat, Gag, Tur. bacak, Chuv. pěç.)

37. FREEZE – C.-Kartv. *set- “freezing” – C.-Sind. *štă- “freezing”. In Dagestanian: Godo sat- “cold”. Among the Indo-European languages, there are only correspondences in the Slavic languages: OSlv. stoudŭ: Rus, Bulg. stud, “cold”, Cz studiti ‘to “cool”, Slvk. stud, Pol. ostuda “chill”. They are mistakenly attributed to the PIE root steu-1 “to push, hit” [VASMER M. 1971. V. III: 786-787]. However, in these words, s is a prefix to the root tud, related to the Ger. Tod "death" (Gmc.*dauþu-). – In Turkic, these isoglosses are matched by C.-Trc. savo- “become cold”, “cool down”, “chill” (Al, Khak, Tuv so:-, Gag, Kum, Kyrg, Tat. dial. su:-, Az, Uygh, soyu- a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 291]. Considering the Azeri and Uyghur words, the С.-Trc. should be soy ← sot, since j most often alternates with t in the Turkic languages [VÁMBÉRY H. 1878: xv].

38. FULL – C.-Kartv. *wes- “filling out”, sa-ws-e “filled up/full” – C.-Sind. *epš- “inflating; blowing out”. In Dagestanian: Bats. d-eps-ar /d-ops-ar “blowing out”, God. wuši “full”.

39. GOOD – C.-Kartv. *maz-a “good” – C.-Sind. *bza “good”, “clean”. In Dagestanian: Darg. dial. marze, Arch. marz-ut “clean”.

40. GRASS – C.-Kartv. *bor-xwen- “(a kind of ) grass” – C.-Sind. *xwǝn “grass, field grass”. In Dagestanian: Bezh. box, Hunz. bǝx, Dido box “grass”,

41. GREEN – C.-Kartv. *çwan- “green, greeness” – C.-Sind. *aj-çwa- “green”.

42. HAIR – C.-Kartv. *bal- “hair; single hair” – C.–Sind: *băr-a “mane; long thick animal, human body hair”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. b-ăl-a „hairy”; Lak. p:al, Darg. bal-a “wool”. Of Avar-Andian languages Bagw. polon “single hair” is noteworthy which likely preserves Andi bol-on – OT jal “mane” [NADELIAYEV V.M., et al. 1969: 227], C.-Trc. *ya:l “mane”, "long hair on the neck of some animals", “hair” (Turkm: ya:l, Tur. ele, Uzb. yol, Chuv. çilkhe a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. (Ed.) 1989: 85] – PIE u̯el-4, u̯elə “hair”, “wool”; “grass, forest” (OInd vāla- “tail”, “hair sieve”, Gr. λῆνος “wool”, Lat. vellus, -eris “fleece”, villus “the shaggy, woolly hair of animals”, Lith. vìlna “wool fiber” and many other [POKORNY J. 1949-1959:1139].

43. HAND – C.-Kartv. *kur- “hand” – C.-Sind. *kwǝ- “hand from wrist to fingertips” – C.-Trc. qol “hand”, “arm” (Alt, Gag, Kaz, Kyrg. Nog, Tur, Turkm, Uz. dial, a.o. qol) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2000: 35-36]. M. Chukhua does not consider Geo. xel-i (ხელი), which has matches in the Dagestanian languages: Lesg, Tab, Ag. χil, Tsa. χilj [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003: 96].

44. HEAD – C.-Kartv. *txam- “crown/head” – C.-Sind. *dǝqw- “back part of throat”.

45. HEART – C.-Kartv. *gwil- “heart” – C.-Sind. *gwǝ- “heart”. Zan (Laz) gur-i →//gu-i, Ming. gur-i “heart” corresponds to Chuv. var "middle", "center", "core", "womb" which refers to C.-Trc. öz (“self”, “mine”, “body”, “core”, “essence”) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974: 506]. The proto-form of Turkic was *gwař (gwarz).

46. HEAVY – C.-Kartv. *gwen- “fat/plump/stout; putting on weight/fattening” – C.-Sind. *gwăn- “heavy/hard”.

47. HOLD – C.-Kartv. *ḳ- “holding; grabbing/touching” – C.-Sind. *ḳ- “grabbing/touching”.

48. HORN – C.-Kartv. *rka- “horn” (Laz. kra) – Pr.-Sind. *ka- “horn”, Hat. ka “horn”. In Dagestanian: Lezg. karč, Ag, Tab. ķarč [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003: 95] – PIE k̂er-, k̂erə-: k̂rā, k̂erei-, k̂ereu- “head”, „horn“ (Gr. κέρας “horn”, Goth. haúrn, OHG, Norse horn “horn”, Lat. cervus “deer” a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 574-577]. M. Chukhua thinks this correspondence is “only an accidental coincidence” [CUKHUA MERAB. 2019:343]. However Tur. karaca, Gag. karaža “roe”. Chuv. karkač “tweaker”, “fork” confirm this relation.

49. HUNT – C.-Kartv. *txew- “hunting, fishing” – C.-Sind. *txă- “abundant and tasty feeding/eating”.

50. I – C.-Kartv. *a-s “I pers. demonstr. pron.” – C.-Sind. *sa- “I/me”. According to Chukhua, this pair “follows an opposite order fixed in Ergative case (cf. Nakh so/sa "I/me" in non-ergative), that corresponds with Urartian ješǝ "I/me". Thus, C.-Sind. *sa- "I/me": C.-Kartv. *a-s- is logical correspondence since in the roots of pers. pron. an order is not fixed even today; cf. Nakh languages -so “I/me”, as 'erg'” [Ibid: 65-66]. In Dagestanian: Arch. zon, Lezg. zun, Tab. uzu, Ag. zun, Tsa, Rut. zi, Kryz, Bud, zin, Udi zu, Khin. zi [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003: 388].

51. ICE – C.-Kartv. *bzar- “frost; ice” – C. –Sind: *bźă- “winter”. In Dagestanian: Lesg. murk, Tab. mirk, Ag. merk, Kryz, Bud, muk „ice“ – C.-Turk *bu:z “ice” (Az, Cr.-Tat, K.-Bal, Kum, Tur, Turkm, a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 238]. In fact, the proto-form should be C.-Trc. buř (burz). The proto-form contained a Nostratic sound rz (cf. Chuv. păr) [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2018]. The length of the root vowel, represented in Turkm. bu:s and Yakut mu:s (both "ice") is associated with the loss of the sound of r – PIE *merk-1, *merĝ-, *merək-, *merəĝ- [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 739-740] and *preus [Ibid: 846]. The PIE protoform is boř (borz): Pol. mróz, Rus, Ukr. moroz “frost”, Alb. marth “severe frost”, Old English freosan, Ger. Frost, Lat. preus- “frieren”, Goth frius “frost”, OInd prusva “drops”, “frost”, “frozen water“ a.o. See FOG.

52. KNEE – C.-Kartv. *muqel- “knee” – C.-Sind. *mǝqa “knee”. In Dagestanian: Av. naku, And. niko, nakwa, Kar. nuku, Akhv. nikwa, Bagv. nikw, Tind. niku, Cham. nikwal, Botl. nuku, nakwa, God. nuku [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003: 80].

53. KNOW – C.-Kartv. *can- “knowing; knowledge”- C.-Sind. *cva- “knowledge”.

54. LAKE – *ṭab-an- “lake; whirlpool” – C.-Sind. *tăm-ǝn “marsh/swamp”. In Dagestanian: Tab, Ag. dagar[Ibid: 203].

55. LEAF – C.-Kartv. *pulk-il- “leaf; sheet of paper” – Pr.-Sind. *puluk-u “leaf”. Hat. puluku “leaf; green”. In Dagestanian: God. χalab, Dido λab, Khvar. λib, Bezh. λibo, Gunz. λibu, Hin. λebu [Ibid: 216] – C.-Trc. bulga:ry “tanned leather “ (Tur. bulgar, Kyrg. bulgary, Kaz. dial. bǔlǧary, Alt. dial. pulǧayry, a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 260] – PIE u̯elk- “leaf”, “wood bark” (OInd. valka-, OIran *varka-: Kurd. balg, Pers. barg, a.o.) [TSABOLOV R.L. 2001: 123, POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 1139].

56. LIVER – C.-Kartv. *Gwiʒel- “liver”- C.-Sind. *ωwǝǯă “yellow”. True parallels are observed in Nakh languages; cf. Ing. ɦinǯar-ilg, Chech. ɦonžar // ɦonǯar “spleen” [CHUKHUA M. 2008: 550] – C.-Turc. baǧyr “lever” (OT, Az, Cr.-Tat, Tur. baǧyr, Bash, Tat. bäγĭr, Uz. baγir, Alt. pagyr, Yak. byar, K.-Bal. bavour, Kaz, Nog. bawyr, Khak. pa:r, Tuv. ba:r, Kyrg. bo:r, Chuv. pěver, etc) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974: 18] – PIE i̯ē̆kʷ-r̥(t-) “liver” (OInd. yákr̥t, Pers. jiga, Avesta yākarə, Arm. leard, Norse lifre, llfr, Gr. ἧπαρ, λιπαρός , Lat. jecur, Mir. i(u)chair , OSlav. ikra, Gmc *libro(n) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 504; KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 432]. All these words are based on a tabooed Nostratic root *gwǝr with different prefixes and suffixes in individual languages.

57. LONG – C.-Kartv. *garʒ-el- “long; lengthening” – C.-Sind. *gǝʒ-a “big”. In the Dagestanian languages: Cham. gwanz-ab, Lak. gwanz-s:a “thick, very big” – C.-Trc. uza-, uzar- “become long”, “last”, “grow”, “be far” [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974: 570-572]. Taking into account Chuv. vărăm “long”, “high”, the proto-form of Turkic words should be *gwuř (gwurz).

58. LOUSE – C.-Kartv. *ṭil- “louse” – C.-Sind. *ṭǝ- “louse”.

59. MANY – C.-Kartv. I. *uxw- “abundant/plenty; lots/many/much”, II. *braw-al “many/much, lots” – C.-Sind. I. *xwa- “abundant/plenty; lots/many/much". II. *baωwa- “multiplying/ increasing in number”.

60. MEAT – C.-Kartv. *leγw- “meat” – C.-Sind. *γwă “meat”. C.-Nakh *laħw-w- “meat kept for winter” – OT laǧzyn “swine” [NADELIAYEV V.M., et al. 1969: 332] – PIE (lē̆ig-2), līg- “body” (Gmc *līka-, Goth. leik “body”, “meat”, Norse līk, OE līc< “body, corpse”, Ger. Leiche “corpse”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 667].

61. MOON – C.-Kartv. *dust-e “moon; month” – C.-Sind. *mǝʒ-ă “moon, month”. In Indo-European languages, the corresponding Kartvelian and Abkhaz-Adyghe words can be put into correspondence OE dūst, Norse dust “dust”, MHG tun(ist “storm”. Ger. Dunst “steam”, “fog”, Let. dvans “steam”, OInd. dhvamsati “crumbles to dust” [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 160-161], OSlav. dǫždĭ “rain” (Rus. dožd’) – All these words are ancient borrowings from an extinct C.-Trc. *dumast ← C.-Trc. dum “drop” + ast “the spatial designation affix” [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974: 195]. This is an enigmatic case; a semantic transformation requires explanation.

62. MOTHER – C.-Kartv. *nen-a “mother /grandmother” – C.-Sind. *năn-a “mother/grandmother” (see FATHER).

63. MOUNTAIN – C.-Kartv. *qad-e “mountain; sheer/steep rock” – C.-Sind. *qad-ă “rock”, „ bank/coast/edge” – C.-Trc. da:ǧ (Az, Cr.-Tat, Kum, Tur. dial. da:ǧ, Tur. dag, Kaz, Kyrg. tau a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1980: 117-118]. Cf. DAY.

64. NAME – C.-Kartv. *ʒax-el- “name”, *ʒax- “calling” – C.-Sind. *xjăʒ-ǝ “name”.

65. NARROW – C.-Kartv. *wiç- “narrow” – C.-Sind. *mǝç- “narrow”.

66. NEAR – C.-Kartv. *i-rgwal- “around, surrounding” – C.-Sind. *argwa- “near/close”.

67. NECK – C.-Kartv. *maṭa- “throat” – C.-Sind. *naṭ ǝ “forehead”. In Dagestanian: Dido, Hunz. maṭa “forehead”, Lak niṭa “face” – C.-Trc. manlay “forehead”, “head”, “front part, nose” a,o. (Turkm. manlay, Kum. maŋglay, Az. dial. maŋay, Bash. dial. manday, Yak. man`ay, Uz. dial. ma:lay a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 40] – PIE u̯er-3: “to turn, wind” (OSlav. vratŭ “neck”→ Rus, Ukr vorot, Cz. vrat, Pol. wrot a.o.) – In Nakh: Chech. worta, Ing. foart “neck”. The words “neck” and “turn” are semantically related, as confirmed by examples in other languages.

68. NEW – C.-Kartv. *maxe “new/fresh” – C.-Sind. *maxjă “weak”.

69. NIGHT – C.-Kartv. *ser- “night; supper” – C.-Sind. *svwă- “night”. Hur.-Urart. šerǝ “evening”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Nakh psar- “evening”, Av. sor-do “night” – C.-Trc. serin “cool, chilly, breezy”, “fresh, refreshing” (Gag, Tur, Turkm. serin, Az. sǝrin, Tuv, Yak. seri:n a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 261].

70. NOSE – C.-Kartv. *niḳel- “nose; chin” – C.-Sind. *nǝḳwă “cheek” – C.-Trc. eŋel “chin”, “jaw”, “cheekbone” [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974: 263-264].

71. OLD – *ʒwel- “old” – C.-Sind. *ʒwă- “old”. In Nakh languages: Chech. ǯöra-baba, Ing. žer-nana//žer-babij “old woman”.

72. ONE – C.-Kartv. *za- “one, single” – C.-Sind. ză “one”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. cha „one“, Rut. sa „one“, Bud. sǝ-b „on“, sa „one“, Khin. sa „one“. Cf. I. The number "one" originates from the first-person singular pronoun in many languages [STETSYUK VALENTYN]. 2020].

73. OTHER – C.-Kartv. *cxwa “another; differnce” – C.-Sind. *xwaǯǝ- “changing”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. zijca- , Ing. xuwca, Av.-And. xis-/xic- , Av. xisize, Bagv, Cham. xisila, Kvar, Hunz. xiža a.o. (all “changing”) – C. -Trc. *bašqa “another; difference” (Az, Kum, Turkm, Tur dial. bašǧa, Bash, Cr. Tat, Kyrg, Tat, Uz. dial. bašqa, Gag, Tur. baška a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 92].

74. RAIN – C.-Kartv. *stowl- “snow” – Pr.-Sind. *stum-il “rain”. Hat. šumil/tumil “rain”. Geo. ts‘vima (წვიმა) „rain“ – in Dagestenian: Dido, Hin. qema „rain“. Cf. SNOW.

75. RED – C.-Kartv. *çit- “being in red”; *çit-el- “red” – C.-Sind. *çǝtǝ- “shining brightly” *çǝtǝ- “shining brightly”.

76. RIGHT – C.-Kartv. *m-arǯw- “right” – C.-Sind. *aʒv- “right”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. ättu, Ing. ätta, Lak. urču, Lezg. erči, Arch. orč “right”, Tab, arčul – C.-Trc. *a:rt “back part”, “back”, “help”, “continuation”, “end” (Az, Alt, Bash, Cr.-Tat, K.-Bal, Kaz, Kyrg, Nog, Tur, Turkm, a.o. art) [Ibid: 179].

77. ROPE – C.-Kartv. *çamas-a “rope; leather strap” – C.-Sind. *çamś-ǝ “rope”.

78. ROUND – C.-Kartv. *ḳurṗ- “round” – C.-Sind. *ḳwǝmṗ- “ball”.

79. SALT – C.-Kartv. *ʒam- “salt” – C.-Sind. *ǯwǝ “salt”.

80. SAY – C.-Kartv. *qel- “saying” – C.-Sind. *ḳwă- “oath/vow, calling out/summoning”. In Dagestanian: Rut. qǝla “learning, teaching, understanding”, Lezg. ḳel-(←*qel-) “id” – OT keläčü, Tur. kelam “word”, Chuv. kala- “speak”, ”say”, “advise”, “teach” [FEDOTOV M.R. 1996: 214-215], Yak. kylan “shout, cry” – PIE kel-6, k(e)lē-, k(e)lā- or kl̥̄-? “to call”, “cry” (Gr. καλέω. Lat. calō, Let. kal’uôt a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 548-550]; PFU *kele or kěle “speak” (Fin. kieli, Est. keel, Veps kel’, Komi, Udm. kyl a.o) [HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 414-415]. Cf. EAR.

81. SCRATCH – *pxan- “scratching” – C.-Sind. *pqă- “scratching”.

82. SEA – C.-Kartv. *ʒaγwa “sea” – C.-Sind. *ʒăωwa “marsh/swamp; large river”.

83. SEE – C.-Kartv. *çq- “seeing, knowing” – C.-Sind. *çωa- “asking/questioning to know sth”. In Dagestanian: Av. čex:-e, Kar. čex:-, Lak. çuxin, Arch. çux(a)-kes “investigating, explorating scurpulously; asking/questioning”.

84. SEED – C.-Kartv. *ʒewal- “hostag; seed” – C.-Sind. *ǯăwla “seed”. In Dagwstanian: Kab. tesǝn, Ub. –sy- “to sow”, Chech. cē “young branches, growth” [ALIROYEV I.Yu. 2005: 215]. In the Kabardian word, te- is a prefix [SHAGIROV A.K. 1977: 71-72] – PIE sē-men-“seed” ← sē(i)-2 “to sow” (OIr. sīl, cymr. hil, Lat. sēmen “seed”, OHG sāmo, OSl. sěmę “seed”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 889-891].

85. SEW – C.-Kartv. *bad- “knitting”, *bad-e “net” – C.-Sind. *bdə- “sewing”. .

86. SHARP – *ser- “sharpening/plastering” – C.-Sind. *λă- “sharpening/plastering; passing (hand…) over sth”.

87. SHORT – C.-Kartv. *ḳoç- “small, little/few, short” – C.-Sind. *ḳăçw- “short”.

88. SIT – C.-Kartv. *sit- “seat” – C.-Sind. *šǝt- “chair”. The correlation *sit-/*šǝt- is supported by Dagestanian data: Arch. š:ent “chair” – PIE sed- “to sit” (OInd. sattá-, Arm. nstim, Gmc *set-ja-st, Lith. sėdė́ti, OSlav sědъ, a.o. ) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 884-887, Kluge 675] – C.-Trc. seki “seat”, “bench”, “dais” (Tur, Turkm. sek, Az, Kaz. dial. sǝki, Uz. dial. söki, Tat. sǝke, Chuv. sak, sakă, a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 271].

89. SKIN – C.-Kartv. *cil- “skin; bark/crust” – C.-Sind. *cwǝ- “skin”.

90. SLEEP – C.-Kartv. *ʒil- “sleep” – C.-Sind. *ǯǝw- “sleep; going/sending to sleep”.

91. SMELL – C.-Kartv. *maγ- “disease; evil; sick/ill” – C.-Sind. *maω “smell/odor”.

92. SMOKE – C.-Kartv. *puḳ- “smoke; steam; fume” – C.-Sind. *ṗḳwǝ- “soot; fume”. In Dagestanian: Lak purḳu “smoke” – C.-Trc. bu:g “steam”, “smoke”, “fog” (Cr.-Tat. dial, Tur. dial, Turkm, Uz. buǧ, Nog. buvo, Gag, Kyr, bu:, a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 229-230].

93. SNAKE – C.-Kartv. *gwel- “snake” – C.-Sind. *gjăw- “whale”. The dubious analogy.

94. SNOW – C.-Kartv. *stow- “snowing” – C.-Sind. *šwǝ- “snow, frost”. In Nakh *tow- “fog/mist” – C.-Trc. sonar “the first snow” (Kaz sonar, Kyrg, Yak. sonor, Tat. sunar, Chuv. khunar a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 329]. – PIE sneigʷh- “snow”, “to snow” (Avesta snaēža-, Gr. νίφα, Cymr. nyf, Ger. Schnee, Let. snìegs, OSlav. sněgŭ a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 974]. Cf. RAIN.

95. STAR – C.-Kartv. *barʒ- “star; late time” – C.–Sind: *bǝǯ-ǝ “evening, twilight/dusk”.

96. SUN – C.-Kartv. *mze “sun” – C.-Sind. *mză “beam/ray, light; light bulb/lamp”.

97. SWELL – C.-Kartv. *ṗixw- “swelling” – C.-Sind. *ṗǝxw- “tip/top/point”. In Dagestanian: Lezg. pix, Kryz pex “blister”.

98. TAIL – C.-Kartv. *ḳam-e “end part of a tail” – C.-Sind. *ḳwa“tail”. In Dagestanian: Darg. ḳimi, dial. ḳume.

99. THAT – C.-Kartv. *-g- “this/that, he/ she/it/that” – C.-Sind. *gj-a “he/she/it/that”. Sindy-Georgian pronouns have correspondences in Dagestanian languages: Lak. ga/ge “he/she/it”, ga-j “they”, Botl. go-v/go-j/go-b “he/she/it”, go-j “they” – C.-Trc. bu: has meanings “this”, “he”, “she”, “it”, “here”, “such”, “there” in different languages. The quality of the consonant in the pronoun in question is not entirely clear. In Turkology, an opinion was expressed about the origin of bu from mu [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 226]. In fact, the long form of the vowel indicates that the basis of the Turkic words should have been *gwu.

100. THICK – C.-Kartv. *bez- “thick, fat/plump/stout” – C.-Sind. *bză “alive; vigorous”.

101. THIN – C.-Kartv. *ḳuç- “narrow, small” – C.-Sind. *ḳuç- “chicken”. In Dagestanian: Khvar. ḳuči, Inkh. ḳuče, Lak. ḳarč “puppy” – C.-Trc. kiči “small” (Turkm. kiči, Alt. kičü, Kyrg. küčü, Tur. kücük, and many others).

102. THINK – C.-Kartv. *γwr- “turning boredom/tedium” – C.-Sind. *γwa- “thinking”. In Dagestanian: Av. urγ-ize, And. urγ-un-nu, Botl. urγ-i, God. urγ-iŋ “thinking”.

103. THREE – C.-Kartv. *sam- “three” – C.-Sind. *’sa- “three”.

104. TOOTH – C.-Kartv. *xac- “tooth” – C.-Sind. *xac- “arrow”.

105. TREE – C.-Kartv. *ʒel- “tree” – C.-Sind. *ǯwă “tree: ash tree, asp, willow”. In Dagestanian: Khin. ʒǝl.

106. TWO – C.-Kartv. *qew- “two” – C.-Sind. *ωwă- “two”. In Dagestanian: Arch. qwe, Hin. qo-no, Tab. qu, Darg. ḳwi, Kub. ḳwe, Hin. ku, Tsa. qo-d – C.-Trc. iki “two”.

107. WASH – C.-Kartv. *swin- “cleaning up” – C.-Sind. *šwǝ – “washing up”. In Dagestanian: Lak. -is:u-n “washing”, Cham. b-učuna, Khvar. esana “to wash” – C.-Trc. suvo – “water”, “river”, “drink” (Alt, Az, Cr.-Tat, Gag, Kaz, Kyrg, Tur, Turkm, Yak. su a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 348-350]. Numerous verbs derived from this word mean «to irrigate», «to flood», «to coat», «to dilute with water», etc. [NADELIAYEV V.M. et al. 1969:515-516] – Gmc *swemma- “swim”, *saiwi- “sea” of unknown origin [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 661, 663]. See WATER.

108. WATER – C.-Kartv. *sim- “water”, “watery, wet” – C.-Sind. *šwan- “liquid/fluid, shedding”. In Dagestanian: Darg. šam-ze “wet, in liquid form”, Tab. šmi//šemi , Ag. š:umer “in liquid form” – C.-Trc. suvo “water”, “river”, “drink”, “tear” (Kaz, Kum, Tutkm, Tur, Uz. su, Kyrg. suu, Khak, Tuv. suǧ, a.o.) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 348]. See WASH.

109. WE – C.-Kartv. *čwen- “we/us” – C.-Sind. *čwă- “we/us”. In Dagestanian: Lezg. čun, Tab. u-ču, Ag. čin “we” – C.-Trc. biz “we” (Az, Cr.-Tat, Gag. Kaz, Kyrg, Tur, Turkm, Uz, a.o. biz, Khak. myz a.o) [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 129-130] – PIE u̯ē̆-1 “we” [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 1114].

110. WET – C.-Kartv. *lub- “wet/moist, damp” – C.-Sind. *Lǝb-ǝ “wet/moist, damp”.

111. WHITE – C.-Kartv. *tetw- “white; silver coin” – C.-Sind. *tătw-a “silver, gold”. The similarity between Geo. თეთრი (tetri) "white" and Chuv. tětre "fog" is striking. The Chuvash word stands somewhat isolated from С.-Trc.*tuman “fog”. It originated from C.-Trc. tüt- "to smoke" (OT tütün “smoke”, Tur tütmek “to smoke”, Bash. tötön, Tat. töten “smoke”, a.o.) [YEGOROV V.G. 1964. 248-249].

112. WHO – C.-Kartv. *wi- “who; where from” – C.-Sind. *wǝ- “it/that”. In Dagestanian: Lak. wa “this”, Khin. wa “over there”, Lezg. wi-nel “over there, upward/above”, Bezh. wa- “deictic article”, Khva. a-w-ed “this” – C.-Trc. bu: “this”, “he”, “she”, “it”, “such”, “here”, “there” [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978.: 225-226]. – PIE kʷo-, kʷe-, fem. kʷā; kʷei- “who”, “when”, “what” a.o. [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 644-648].

113. WIDE – C.-Kartv. *ser- “wide/broad; long” – C.-Sind. *šăr- “smooth”. In Nakh: Chech. šüjra, Ing. šera, Bats. šora “broad” – Ukr. šyr “width”, šyrokyi, Pol. szeroki, Cz. široký a.o. Slavic “wide, broad”. The family ties are unclear [VASMER M. 1973: 442].

114. WIND – C.-Kartv. *psin- “cold wind, breeze” – C.-Sind. *pśǝ- “wind/blowing” – PIE bhes-2 “to blow” (OInd. bábhasti, Gr. ψύ̄-χω). Probably sonic root [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 146].

115. WING – C.-Kartv. *pswel- “wing” – C.-Sind. *psăw- “bird, wing”.

116. WOMAN – C.-Kartv. *col- “woman, wife” – C.-Sind. *cal- ”daughter/sister-in-law”.

117. WORM – C.-Kartv. *γwançw- “worm” – C.-Sind. *ωwănçw- “lizard”. In Dagestanian: Lezg. γüč “moth”.

118. YEAR – C.-Kartv. *çel- “year” – C.-Sind.*çă- “time, season” – C.-Trc. jyl “year” (Bash, Gag, Kum. Nog, Tat. jyl, a.o.) [SEVORTIAN E.V., LEVITSKAYA L.S. (Ed). 1989: 276].

119. YELLOW – C.-Kartv. *γuw- “glowing red, yellow” – C.-Sind. γwǝ- “red, yellow”.

120. YOU – C.-Kartv. *stwen- “you (pl)” – C.-Sind. *šwă – “you (pl)”. Nakh (Chech, Ts.-Tush. šu, Ing. šo “you (pl.)” and in some Dagestanian languages; cf. Tsa. šu “you (pl.)” – PIE se- “reflexive pronoun” (OInd. sī-m, Lat. sibī, Ger. sie, Celt, siǝ, Gr. ἵ a.o) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 882-884] – C.-Trc. siz, *sen (Az, Kaz, K.-Bal, Kum, Kyrg, Tat, Turkm, Tur siz, a.o. [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 271]; Kaz, K.-Bal, Kum, Kyrg, Tat, Turkm, Tur, Uz. sen, a.o. “you (sing)” [Ibid: 247-248].

As it turned out, 51 correspondences to Sindian etymons were found in the Nostratic languages. Such a number may indicate their common origin, that is, the inclusion of Sindian languages in the Nostratic language. This assumption raises the question of the relationship between the Nakh-Dagestani languages and the Nostratic languages, as 42 of the 52 correspondences are from the Nakh-Dagestani group. However, there may be more, as separate Nakh-Dagestani correspondences without analogs in Sindhi are possible. Their search was made using the available materials.

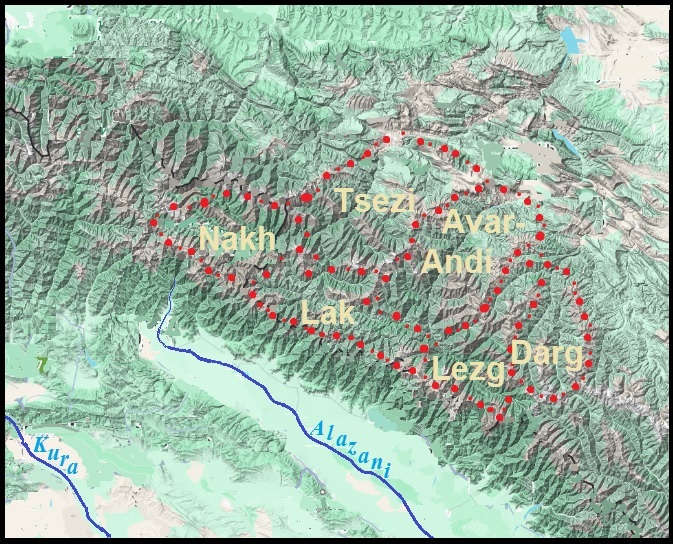

Fig. 2. Areas of formation of the Nakh-Dagestanian languages in the eastern part of the North Caucasus.

The boundaries of the areas of language formation are marked with red dots. The abbreviations Lezg. and Darg. refer to the Lezgin and Dargin languages, respectively.

The Nakh-Dagestanian language family consists of the Dargwa and Lak languages and the following language groups: Nakh, Avar-Andi, Tsezi, and Lezgian. It follows that initially the Dagestanian family consisted of six languages, that is, each of the mentioned groups has its proto-language, which we will call Nakh, Avar-Andean, Tsezi, and Lezgin. The kinship between them and the search for the place of their formation was carried out using the graphoanalytical method on the materials of the Tower of Babel. The constructed graphic model of their kinship allowed us to localize the ancestral home of the Dagestanian languages in the mountainous country of the North Caucasus. The map in Fig. 2 shows it. The boundaries of the areas of formation of individual languages were mountain ranges.

The Nakh group of languages includes Chechen and Ingush, which are called Vainakh, Batsbi, and Kisti. The once common Avar-Andean language eventually split into the following daughter languages: Akhvakh, Andi, Avar, Bagval, Botlikh, Chamal, Godoberi, Karata, and Tindi. The paternal Tsezi language gave rise to the following languages: Bezhita, Hinulh, Hunzib, Inkhoqwary, Khvarshi, and Dido. Over time, the common Lezgin language developed into the Agul, Archi, Budukh, Khinalug, Kryz, Rutul, Tabasaran, Tsakhur, and Udi languages, and the modern Lezgin. Such a large number of related languages ensures greater preservation of the most ancient roots in the words of modern languages. Having disappeared for various reasons in some, they are present in others. To date, several comparative and contrastive dictionaries of the Caucasian languages have been published. Some of them are etymological dictionaries of language families with the systematic use of proto-language constructions. A dictionary that combines the main original and colloquial vocabulary of all autochthonous Caucasian languages, reflecting the main range of natural everyday objects, will be well suited for our research [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003]. The dictionary contains an index in which you can find entries related to almost all words ща the lexical core.

To compare our results with those of previous studies and determine the degree of connection between the Nakh-Dagestanian languages and the Nostratic languages, we will continue to search for matches to the verified list of 140 lexical core words. The results of the searches are presented below.

BLOW – PIE pū̆-1, peu-, pou-n: “to blow, blow up” (Arm. pʿukʿ “breath, wind”, MHG fochen “blow”, Lith. pũsti “blow”, Let. pũga “gust of wind” [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 847-848] – In Dagestanian: Av. pujze, And. pudu, Kar. puvaλa, Tind. povoλa, Cham. pula, Bagv. purila, pudila, Hun. puλa, Hin. peλa “blow”.

CHILD – PIE bher-1 “to bear” (Goth, Norse, OHG barn “child”, OLith. bérnas “child”, Let. bę̄̀rns “child”) [Ibid: 128-132] – In Nakh: Chech, Ing. ber, Bats. bader “child”.

COLD – C.-Trc. sovoa “get cold” (Tur. so:u-, Kaz, Nog, Tat. dial. suvoy-, Kum. suvu-, Gag, Kum. su:- a.o.). [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2003: 291] – In Dagestanian: Tind. sa-b, Cham. sāv-b, God. saji, sati “cold”.

DIRT – PIE gʷor-gʷ(or)o- “dirt” (Arm. kork, Gr. βόρβορος) [Ibid: 482] – C.-Trc. *qork “to fear” (Az, Gag, Kaz, Kum, Kyrg, Nog. qorq, Bash, Tat. qurk a.o. “to fear”) – In Dagestanian: Av. čoroka-b, Akhv. čorokada, Dido čorokaw; PIE (s)ter-8 “dirty water, mud, smear” (Gr. στεργάνος. Lat. sterkus, OHG *þrekka “dirt”, Ger. Dreck “dirt”, excrement”, Lith. teršti "to dirt") [Ibid: 1031-1032] – In Dagestanian: Darg. žargasi, Lezg, Tab. čirkin, Ag. čirkimf, Kryz, Bud. čirklu “dirt”.

DRY – C.-Trc. qu:ra “dry”, “to dry”, "hard dry soil", “desiccate”, “wither” (Alt, Az, Gag, Kyrg, Turkm, Uzb. quru-, guru-, qury-) [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 2000: 157] – In Dagestanian: Arch. quritu-t, Lezg, Tab. quru, Ag. ruguf, urgar, Tsa. Guru-n, Rut. Gurud, Udi qari “dry”.

EGG – PIE ō(u̯)i̯-om “egg” (Arm. ju, Gr, ὠιόν, Cymr. wy, uy, Gmc *āii̯am, OClav. ajĭce s.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 783-784] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. hoa, Av. xono, hono, Akhv. hanu “egg”.

FAT – PIE madz-d ”food”, “dish” (OInd. mēdas- “fat”, Pers. māst “sour milk”, Alb. manj “feed”, “fattening”, “acorn fattening”, OHG mast “fattening”) [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 466] – C.-Trc. may “fat” (Alt, Bash, Kaz, Kyrg, Nog, Tat. may “fat”) – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Bats. moh, Ing. muh, Dido mo, Khvar. mu, Bezh. mähä, Hin. mä „fat“.

FLOW – PIE akʷā- “water”, “river” (Lat. aqua “water”, “aqueduct”, Gmc agwijō “water”, Goth. aƕa “river”, Norse ǫ́, OE ēa, a.o.) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 23] – C.-Trc. aq- “flow”, “stream” (Az. aqmak, Gag. agmaa, Kaz aǧu, Kyrg. aǧuu a. o. “to flow”) – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing. d-axa, Bats. ixar, Av. čwaxize, Akhv, čwaxilo, Botl, God. čwaxadi, Hin. r-aqa “to flow”.

FLY – PIE lek-2 in words for “bend”, “jump”, “fly” (Lith. lekti “fly”, “run”, Let. lekt “fly”, “jump”, Ger. löcken „jump“, “kick”, Gr . λακτίζω “kick”, OBulg. letěti, Rus. letet’ a.o. similar Slavic “fly”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 673; FRISK H. 1960-1972: 673] – Kab. λǝtǝn “to fly”. In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing. lela, Lak. lexlan, lexan “fly”, And. λubdu, Rut. lä-w-čäs „jump“.

FOOT – PIE kok̂sā “a part of body (foot, hip, etc.)” (Lat. coxa “hip”’, OIr. coss “foot”, Ger. Hachse “lower leg”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 611] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing kog, Bats. kok, Khvar. kaka, Lezg. kwač “foot”; PIE lek-2 in words for “bend, “jump” (Norse leggr “lower leg”, Dan. læg, Swed. läg "the calf of the leg" a.o.) – In Dagesten: Tab. lig, Ag. lek, Rut. ʁil “foot”. See FLY.

HE – In the Nakh-Dagestanian languages, words similar to the first, second, and third person singular pronouns in Indo-European languages are used for the third person singular pronoun.

HEAD – see HEART.

HEART – PIE (k̂ered-:) k̂erd- “heart” (Hit. ka-ra-az, Arm. sirt, Gr. καρδίᾱ, Gmc hertōn “heart”, but OIr. cretim, Lat. crēdō “believe”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 579-580] – Chech, Ing, korta, Bats. kort, Arch, karti “head”.

KNOW – PIE ĝen-2, ĝenə-, ĝnē-, ĝnō- “to know” (OInd. jānā́mi, Arm. cancay, Gmc *kann-eja, Lith. žinaũ, žinóti, Let. zinât a.o.) [Ibid: 376-378] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. xaa, Ing. xa- “to know”, Chech. gan, Bagv. hēna, Lezg. akun “to see”.

LIE – PIE legh- “to put down, to lie down” (Gr. λέχεται, Lat. lectus, OIr. lige, Gmc *leg-ja, OSlav. ležati, a.o.) [Ibid: 658-659] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing. d–illa, Bats. d-illar, Av. λeze, Tind. b-iλiλa, Ud. lax(e)sun, Hin. liqiqi “put down“, “lay down”.

LOUSE – PIE ghnei-, ghneid(h) “nit”, “louse egg” (Gmc hnitō, Rus, Pol. gnida, Let. gnīda) [Ibid: 437] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing. maza, Bats. maç, Ag, nit, Av. nač, And. noči, Lak. naç, Darg. nez, Lezg, Ag, Rut. net, Tab. nic, a.o. “louse”, “nit”, “louse egg” .

MANY – PIE dheugh- ‘to touch, press, milk”; “donate generously” (Lith. daug, Let. daudz “many, much”, Ukr. duže “very”, Gmc daug, OE dugan “be suitable, useful”) [Ibid: 271] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech, Ing. duqa, Bats. duq, Khvar. docon, Darg. dagal, Arch. dugāla “many, much”.

NEW – PIE i̯eu-3 “young” (OInd. yúvan- , Avesta yvan. Lat. juvenis, Lith. jáunas, Let. jaûns a.o.) [Ibid: 510-511] – C.-Trc. yaŋy “new” (Alt, Bash, Cr.-Tat, Nog. yaŋy, Tat, Uzb. yaŋa a.o “new”); In Nach-Dagestanian: Chech. çina, Ing. çena, Bats. çini, Bagv. çinu-b, Dido eçno, Khvar, eçnu, Rut. çindi a.o. “new”.

NIGHT – PIE nekʷ-(t-), nokʷ-t-s “night” (OInd. nák, Gr. νύξ, Lat. nox, Gmc naht-, Lit. naktìs, a.o. “night”, Hit. neku- ’dawn”, Toch. B nekciye “at evening”) [Ibid: 62-763] – In Dagestanian: Hunz. niše, Hin. neši “night”, Bezh. niše, Lezg. neʁen, Rut. nax “evening”.

OLD – PIE ĝen-1, ĝenə-, ĝnē-, ĝnō- “to bear” (OInd. jánati “creates, gives birth”, Gr. γενετή “birth”, γένος “sex, lineage, family, genus, etc”, Arm. cnauɫ “father”, Gmc genǝ “give birth” a.o) [Ibid: 373-375] — Chech qena, Ing. gäna, Bud kinǝ, Hin. köny “old”.

ROUND – PIE (s)kregh- ← (s)ker-3 “to turn, bend” (Gmc hrenga- “ring”: OE, OHG hring, a.o. “ring”, OSl. krǫgŭ “circle”: Rus. krug, Pol. krąg, a.o. “circle”) [Ibid: 935-938] – In Nakh-Dagestanian: Chech. gourga, Ing. gerga, Bats. gogri, Av. gurgina –b, And. gurguma, Kar. gerganu-b, Tind. korkalu-b, Tab. gergmi, Kryz gurgum a o. “round”.

SCRATCH – PIE gerebh- “scratch” (Gr. γράφω, Gmc. *kerba-: OE ceorfan, Ger. kerben a.o.) [Ibid: 392] – Darg. ʁirbires „scrub“, Tab. kraxub „rub“.

SEW – PIE tek-3 “to weave, plait”, tek̂þ- “to plait” (Ossetic taxun “to weave”, Arm. tʿekʿem “to twist, braid, wrap”, Lat. texō “to weave, plait”, Hit. takš-, takkeš “to put together” [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 1058-1059] – In Nakh: Chech, Ing. tiega “to sew”.

SHARP – PIE ak̂-, ok̂- “sharp” (Gr. ἀκίς, -ίδος “point, thorn”, Lat. aciēs “sharpness, edge”, OE ecg “corner, cutting edge”, OHG ekka “tip, “sword edge”, Ger. Ecke “edge” a.o.) [Ibid: 18-22] – In Dagestanian: Bezh. ȁçço, Hunz. açu, Tsa. eki-n, Bud. jeqi „sharp“.

STAND – Ger. Latte, OE lætt “bar, rack, rod”. The assessment of in-sound geminate is difficult [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 429], Rus, Ukr. lata, Pol. łata “patch”, Serbian latitsa “gusset”, Gr. λωτός “plaited in” [VASMER M. 1967: 464], OE læt “slow, careless, sluggish, late”, OSlav. lēto “year”, Lat. latns “broad" – In Nakh: Chech, Ing. latta, Bats. lattar “to stand”. Chech. latta 1. “to stand, keep, hold on”, 2. “to last, continue” from Chech. latō 1. "to stick”, 2. “to patch”.

THICK – PIE tenk-to- “solid”,” thick’ (Gmc *þenh-a- “thrive “, Ger. dicht, Lith. tankus “tight”, Avesta taxma “fest, tight“. Ukr. t’aknuty „nützen”) [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 1068], OSlav. *tǫča “downpour”, “snow flurry” [FRAENKEL E. 1962-1965: 1056]. PIE stā-: stə- “to stand’ with -m formants (Lith. stomuõ “stature”, Rus. stamík “support beam”, Toch. A ṣtām, B stām “tree” a,o.) [POKORNY J.: 1004-1010] – In Nakh: Chech. stuomma, Ing. soma, Bats. stami “thick”.

WOMAN – PIE gʷē̆nā “woman” (OInd. gnā, Avesta. gənā, Arm. kin, Gr. γυνή, Alb. zonjë, Goth. qino, Oslav. žena a.o.) [POKORNY J. : 473-474] – In Dagestanian: Khvar. ʁine, Kryz xinib, Hin. xinemkir Darg. xunul, Dido ʁanabi“woman”.

The given list contains 25-26 correspondences between the Nakh-Dagestanian and Nostratic languages in the words of the lexical core. Knowing the correspondences considered earlier, generally, there should be more than sixty of them, significantly more than the correspondences between the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nostratic languages. This convincingly demonstrates the genetic relationship of the Nakh-Dagestanian and Nostratic languages. At the same time, in the Nakh-Dagestanian languages, the correspondences to Nostratic are found in the Indo-European languages. In the Nakh-Dagestanian languages. On the contrary, in the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages, most of the correspondences are found in Turkic, fewer than in the Indo-European languages. This has its explanation. As already indicated, the Nostratic languages were formed in the region of the three lakes. Between this region and the mountainous country of Dagestan, there is a space on both banks of the Kura River, which must have been populated by contemporaries of the Indo-Europeans, whose ancestral homeland was determined to be on both banks of the Araks. These people must have been the ancestors of the speakers of the North Caucasian languages, who at some time crossed the Caucasian ridge and settled on its north-eastern slopes. There is no clearly defined geographical boundary between the areas of formation of the Proto-Dagestanian and Proto-Indo-European languages, which suggests good language contact between the speakers of these languages. The Proto-Nakh languages began to form along the banks of the upper Kura. The boundary between their speakers and the ancient Kartvelians was the Surami ridge (see map in Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Areas of formation of the Nakh-Dagestanian languages in the eastern part of the North Caucasus.

Fig.3 Formation of Proto-European languages in Transcaucasia

The genetic relationship between the Abkhaz-Adyghe, Nakh-Dagestian, and Nostratic languages does not contradict the existence of a special Caucasian language family. Its existence is due to the proximity of the peoples inhabiting the Caucasus. Due to the intensive exchange of lexical words of later origin compared to the time of formation of the lexical core words, the number of lexical correspondences in the Caucasian languages far exceeds their size. However, there are no grounds for assuming the existence of a special Proto-Caucasian parent language. It does not even have a place of formation on the territory of the Caucasus and the surrounding area. This is a kind of phantom that helps to limit the language family to establish the typological relationship that exists between them.

The Caucasus began to be populated by modern humans after they appeared in the Levant. Moving from the Levant through Asia Minor, these people found the most convenient place to settle in the Caucasus Mountains. Looking for refuge in the cold season, Paleolithic man mastered cave dwellings in the Caucasus much earlier than in the neighboring regions of the Middle East. The Caucasus is one of the first places (and possibly the first) by the number of sites of Stone Man [LUBIN V.P. 1998: 49]. The first man’s intense colonization of the Caucasus occurred in the Acheulean times (Lower Palaeolithic era), although archaeological finds of earlier times are also known.

By the end of the Acheulean period, people had already invaded the territory of modern Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the North Caucasus (sites in Azykh cave, Dmanisi, Kudaro, Muradovo, Tsona, Karakhach).

Fig. 4: Azokh cave in Azerbaijan, the site of pre-Neanderthal people. Photo from Wikipedia.

It is usually assumed that the cradle of human civilization was the so-called «Fertile Crescent.” This territory is, indeed, a crescent on the fertile lands between the Mediterranean and the Iranian Plateau and is bounded on the south by the Arabian desert and on the north by the ridge of Jabal Sinjar.

However, before the development of agriculture, this territory was not attractive to ancient man. On the contrary, the locality around three lakes was very comfortable for settlements because it had favorable geographical and natural conditions for primitive life. The surrounding area consists of many mountain ranges and plateaus between deep troughs. There are many mountains of typical volcanic origin, the most famed of which are the Ararat and Aragat.

The people who settled the Caucasus were one of the proto-European tribes. They spoke one primary language, from which the so-called Nostratic and others developed. Assumptions can be very different. We can talk more confidently about the Hattic language, but other European languages, including Etruscan and Basque, can also belong to them. Thus, the genetic relationship of European languages goes far beyond the Nostratic, so it is only conditional to speak about the paternal Nostratic language, as well as the Proto-Caucasian. This macrofamily can be considered only from a theoretical point of view as an example of methods for studying the relationship of languages.

Abbreviations

Ab. – Abaza

Abkh – Abkhaz

Ag. – Agul

Akhv. – Akhvakh

Alt. – Northern Altai

And. – Andi

Arch. – Archib

Arm. – Armenian

Av. – Avar

Az. – Azerbaijani

Bash. – Bashkir

Bats. – Batsb

Bagv. – Bagval

Bezh. – Bezhit

Botl. – Botlikh

Brert. – Breton

Bud. – Budukh

Bulg. – Bulgarian

C. – common

Cham. – Chamal

Chech. – Chechen

Chuv. – Chvash

Cr.-Tat. – Crimean Tatar

Cymr. – Cymraeg

Cz. – Czech

Dag. – Dagestanian

Dan. – Danish

Darg. – Dargwa

Eng. – English

Est. -Estonian

Fin. – Finnish

Geo. – Georgian

Ger. – German

Gmc – Germanic

God. – Godobery

Goth. – Gothic

Gr. – Greek

Hat. – Hattic (Hattian) l

Hin. – Hinukh

Hit. – Hittite

Hunz. – Hunzib

Hur. – Hurrian

I-E – Indo-European

Ing. – Ingush

Inkh. – Inkhoqwary

K.-Bal. – Karachay -Balkar

Kab. – Kabardin

Kar. – Karata

Kartv. – Kartvelian

Khak. – Khakas

Khin. – Khinalug

Khvar. – Khvarshi

Kum – Kumyk

Kurd.- Kurdish

Kyrg. – Kyrgyz

Lat.- Latin

Let. – Lettish

Laz – Lazuri

Lezg. – Lezgian language

Lith. – Lithuanian

MHG – Midlle High German

Ming. – Mingrelian

Mir. – Middle Iranian

Nog. – Nogaic

OBulg – Old Bulgarian

OE – Old English

OHG – Old High German

OInd – Old Indian

OIr – Old Irish

OIran – Old Iranian

OSlav – Old Slavic

OT – Old Tirkic

Pr. – Proto

Pers. – Persian

PFU – Proto-Finno-Ugrian

PIE. – Proto-Indoeuropean

Pol. – Polish

Rus. – Russian

Rut – Rutul

Sind. – Sindy

Slvk. – Slovakian

Swed. – Swedish

Tab. – Tabassaran

Tat. –Tatar

Tind. – Tindi

Toch. – Tocharian

Trc – Turkic

Tsa. – Tsakhur

Tur. – Turkish

Turkm. – Turkmen

Tuv. – Tuvan

Ub. – Ubykh

Udm. – Udmurt

Ukr. – Ukrainian

Urart. – Urartian

Uygh -Uyghur

Vain. – Vainakh

Yak. – Yakut

References

VY – Voprosy yazykoznaniya. – (In Russian) – The journal “The Questions ofLinguistics”. Moscow.

ALIROYEV I.Yu. 2005. Chechensko-russkiy slovar’. M. – (In Russian) – Chechen-Russian Dictionary. Moscow.

ARAPOV M.V., HERZ M.M. 1974. Matematicheskie metody v istoricheskoy lingvistike – (In Russian) – Mathematical Methods in Historical Linguistics. Moscow.

BOMHARD R. ALLAN. 2014/2015. The Nostratic Gypothesis in 2014//Mova ta istoria. Issue 359. Kyiv.

BOMHARD R. ALLAN. 2018. A Comprehensive Introduction to Nostratic Comparative Linguistics. Florence. SC.

CHUKHYA M. 2008. Συγκριτική γραμματική των ιβηρικών-ιτσκερικών γλωσσών – (In Geothian) – Comparative grammar of Iberian-Ichkerian languages, Tbilisi.

CUKHUA MERAB. 2019. Georgian-Circassian-Apkhazian Etymological Dictionary. Tbilisi.

FEDOTOV M.R. 1996. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ chuvashskogo yazyka v dvukh tomakh – (In Russian) – Etymological Dictionary of the Chuvash Language. Two volumes. Cheboksary. Chuvash State Institute of Humanities.

FRAENKEL E. 1962-1965. Litauisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Band I und II – (In German) – Lithuanian Etymological Dictionary. Volume I and II. Heidelberg. Carl Winter. Universitätsverlag.

FRISK H. 1960-1972. Griechisches etymologisches Wörterbuch – (In German) – Greek Etymological Dictionary. Bände I-III. Heidelberg.

HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007. Nykysuomen etymologinen sanakirja. Helsinki. WSOY. – (In Finnish) – Etymological Dictionary of Present-Day Finnish. Helsinki. WSOY.

KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M. Sh. 2003. Slovar’ kavkazskikh yazykov – (In Russian) – Dictionary of Caucasian Languages. Moscow . “East Literature”. RAN

KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. 22 Auflage. Berlin-New York. – (In German) – Etymological Dictionary of the German Language. The 22nd Issue. Berlin-New Yorrk.

LEVITSKAYA L.S., DYBO A.V., RASSADIN V.I. 1997. Etimologicheckiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykov – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letter “K”, “Q”. Moscow. “East Literature”.

LEVITSKAYA L.S. , DYBO A.V., RASSADIN V.I. 2000. Etimologicheckiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykov. – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letter “Q”. Moscow. “East Literature”.

LEVITSKAYA L.S. BLAGOVA G.F., DYBO A.V., HASILOV D.M. , POTSELUYEVSKIY E.A. 2003. Etimologicheckiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykov. – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letter “L”, “M”, “N”, “P”, “S”. Moscow. “East Literature”.

LUBIN V.P. 1998. Peschery Kavkaya i czelovek v predistorii s v istoricheskoe vremia – (Rus) – Caves of the Caucasus and the man in the prehistory and in historical time. Arkheologіa. No 4.

MAŃCZAK WITOLD. 1981. Praojczyzna Słowian. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk- Łódź. – (In Polish) – The Urheimat of Slavs. Wroclaw-Warsaw-Kraków.-Gdansk- Łódź.

MELNYCHUK A.S. 1991. O vseobshchem rodstve yazykov mira – (RusIn Russian) – About General Relationship of Languages of the World. VY. № 2.

NADELIAYEV V.M., NASILOV D.M., TENISHEV E.R., SHCHERBAK A.M. 1969. Drevnetyurkskiy slovar’. Leningrad. – (In Russian) – Old-Turkic Dictionary. Leningrad.

POKORNY J. 1949-1959. Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch – (In German) – Indo-European Etymological Dictionary. Bern.

SEVORTIAN E.V. 1974. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykjv – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with wovel. Moscow. “Nauka”.

SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykjv – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letter “B”. Moscow. “Nauka”.

SEVORTIAN E.V. 1980. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykjv – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letters “V”. “G”, and “D”. Moscow. “Nauka”.

SEVORTIAN E.V. , LEVITSKAYA L.S. (Ed). 1989. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ tyurkskikh yazykjv – (In Russian) – Etymological dictionary of Turkic languages. Common Turkic and Inter-Turkic stems starting with the letters “Ž”, “Ž’”, and “J”. Moscow. “Nauka”.

SHAGIROV A.K. 1977. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ adygskikh (cherkesskikh) yazykov – (In Russian) – Etymological Dictionary of Adyghe (Circassian) Languages. Moscow. Nauka.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998. Doslidzhennya peredistorichnikh etnogenetichnikh procesiv u Skhidniy Yevropi. Persha knyga. L’viv–K. – (In Ukrainian) – The Research of Prehistoric Ethnogenetic Processes in Eastern Europe. Volume 1. Lviv- Kyiv.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2009. Ethnicity of the Ancient Population of the Caucasusю. Academia.edu.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2010. Far East: The Relationship of the Altaic

and Turkic Languages. Academia.edu.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2018. The Hypothetical Nostratic Sound RZ: To the Problem of Rhotacism and Zetacism. Academia.edu.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2019. Reasoning on the Origin of the Human Language// Macrolinguistics. Vol. 7. № 1 (Serial № 10). The Learned Press.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2020. Reasoning on Primary Formation of Numerals in the Nostratic Languages. Academia.edu.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2023. The Formation of the Sino-Tibetan Languages and their Speakers Migration. nn Academia.edu.

STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2024. Proverka rodstva mongol’skogo i tyurkskikh yazykov leksikostaticheskim metodom – (In Russian) – Verification of the relationship between Mongolian and Turkic languages using the lexicostatic method. Academia.edu .

STRINGER CHRIS. 2007. The origin and dispersal of Homo sapiens: our current state of knowledge//Rethinking the human revolution. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research Monograph series, Cambridge. pp. 15-20. Academia.edu

SWADESH M. 1960. Leksikostatisticheskoe datirovanie doistoricheskikh etnicheskikh kontaktov. Sb. «Novoe v lingvistike». – (In Russian) – Lexical-Statistical Dating of Prehistoric Ethnic Contacts: The New Aspects in Linguistics. Issue 1. Moscow.

TRAUTMAN REINHOLD. 1948. Die slawische Völker und Sprachen. Eine Einführung in die Slawistik. Leipzig. – (In German) – The Slavic Folks. An Introduction to the Slavistics. Leipzig.

TSABOLOV R.L. 2001, 2010. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ kurdskogo yazyka – (In Russian) – Etymological Dictionary of the Kurdish Language. Volumes I and II. Moscow. Publishing company «Eastern Literature». Russian Academy of Sciences.

VÁMBÉRY H. 1878. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der Türko-tatarischen Sprachen. Leipzig. F.A. Brockhaus.

VASMER M. 1964-1973. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ russkogo yazyka – (In Russian) – Etymological Dictionary of the Russian Language. Moscow.

YAKUSHIN B.V. 1985. Gipotezy o proiskhozhdenii yazyka – (In Russian) – Hypotheses about Origin of Language. Moscow. Nauka.

YEGOROV V.G. 1964. Etimologicheskiy slovar’ chuvashskogo yazyka – (in Russian) – Etymologiacal Dictionary of the Chuvash Language. Cheroksary.