From the Alans to the Svans

From the very beginning, I must make a reservation that I am breaking through an open door, proving that the Alans were Anglo-Saxons, because even in the time of Flavius Honorius (384-423), the Romans considered them Goths, i.e., the same Germanic people as the Anglo-Saxons:

Vandaly, Maeotodis paludus, fame pressi, ad Germanos, quos hodie Francos nominant , et flumen Rhenum se receperunt, tractis in societatem Alanis, natione Gothica. Inde Godigiseli ductu in ea parte Hispaniae, quae oram nabet imperii Romani primam ab occano, fedes fixerunt (Strittero Johanne Gotthilf. MDCCLXXIX, 336).

Also, Procopius of Caesarea reasonably (sic!) ranked the Alans among the Gothic peoples (ibid, 319). No doubt, many Western historians (DAVIES NORMAN. 2000: 241 a.o.), this has long been known, but they did not delve deeply into the question of the Alans' ethnicity due to the lack of convincing evidence of the Anglo-Saxon presence in Eastern Europe. Even now, these facts remain little known. The development of this topic has allowed for a reconsideration of the history of the Khazar Khaganate (see Khazars – Khevsurs) and opened up new perspectives, which will be outlined here.

Currently, due to the fault of Soviet specialists, the prevailing opinion is that the Alans were Iranian-speaking and mainly because the alleged descendants of the Alans, like Ases, Ossetians belong to the Iranian language family (BRAUN F. 1899: 96). However, the study of historical sources and works of historians devoted to the Alanian theme gives reason to consider this opinion erroneous:

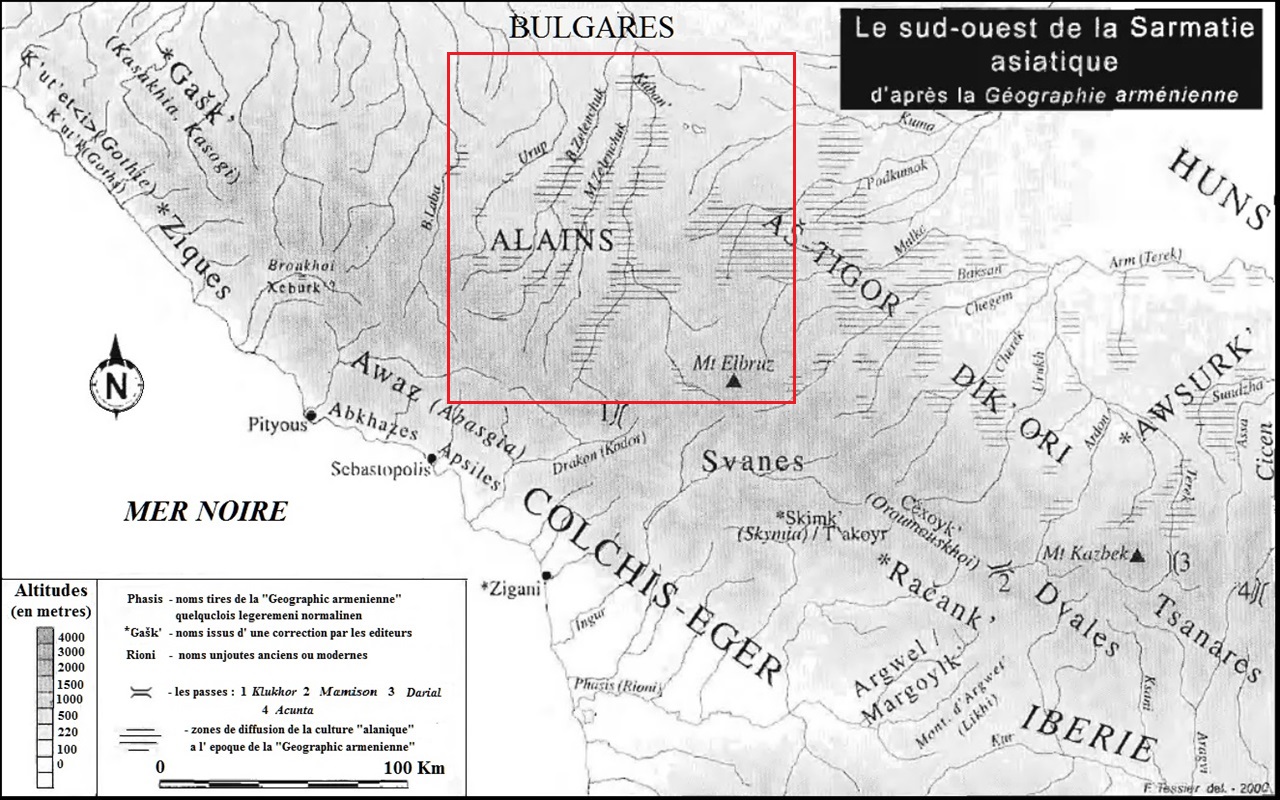

So, having discarded the walking stereotypes, it is necessary to divide the ethnic unit of “Alans” into Alans, on the one hand, and Ases, on the other. This dichotomy is confirmed for an earlier era by other sources, primarily “Armenian geography” (ZUCKERMAN C. 2005: 69).

Recognizing this conclusion as a whole, other scholars have their own opinion about the Ases and Alans, when evidence is given in favor of their Turkic origin, but such publications remain unknown to a wide circle of readers (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010; MIZIEV I.M. 2010-1 a.o.). In contrast, works restoring the history of Alan in the Iranian mainstream are very popular. An example of this can be the well-known work of A. Alemany (ALEMANY AGUSTI. 2000), which is largely based on the works of V.I. Abayev. Abayev is considered a great authority in psychology despite his obvious association with his nationality. His field of research is rather narrow, in particular, the epigraphy of the Northern Black Sea region, which he deciphered mostly erroneously because he did it only with the help of Iranian languages. At the same time, he overlooked many facts that could have led his research to the true path. For example, with his rich imagination, he didn't suppose the possibility of Ossetian origin for such place names as Azov, Vorskla, Kalitva, Oskol, Sochi, and other names without reliable etymology.

Similarly, other reputable scientists arbitrarily manipulate the facts and archaeological cultures, but without regard to linguistics, at ease draw their history of the Alans, for example, Tadeusz Sulimirsky (SULIMIRSKI T. 2008). However, when their ancestral home was being searched for somewhere in Asia, considering that the Iranian people had arisen only there, the Ossetians had to have come from Asia.

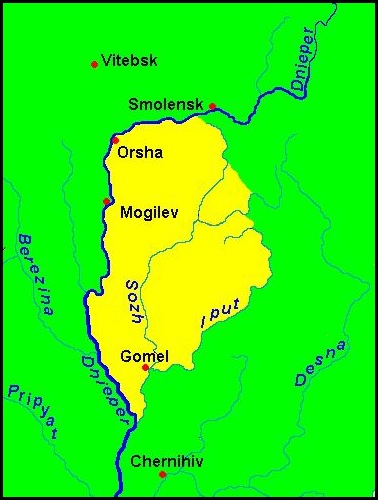

However, their Urheimat was in the upper reaches of the Dnieper River, and this fact has been evidenced in the place names of the nearest locality (see the section Iranic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age).

At left: The Ancestral home of the Ossetians (yellow)

Long before the Scythian period, the Ossetians had been forced from their ancestral homeland by Baltic tribes arriving from the right bank of the Dnieper. They had to migrate southward, and for a while lived in the neighborhood with Mordvinians (as evidenced by the Ossetian-Mordvin lexical matches). The Ossetians appeared in the area of the Lower Don River only in the Sarmatian period. At the same time, the upper reaches of the Dnieper were populated by people known in the Pontic steppes under the name of Alans:

According to the Greek geographer Marcian (or pseudo-Marcian) from Heraclea Pontica (ca 400 AD), "… the Rudon river flows from the mountain Alan, about this mountain and in general, in this country, a large area was inhabited by people of the Alans-Sarmatians, there were sources of Borisphen in their lands, which flows to Pontus. The land along the Borysthenes behind the Alans was inhabited by the so-called European Huns… " (Marcian P.: 39, quoted by LATYSHERV V.V. 1899). It is well known that Borisfen in ancient sources is the Dnieper River, while Rudon is one of the rivers of the Baltic Sea (KAZANSKIY M.M., MASTYKOVA A.V. 1999: 119).

The testimonies of ancient authors do not allow us to conclude the ethnicity of Alans; furthermore, their assessments of the related connections of the described peoples, for the most part, seem to be conjecture. It is appropriate to recall the prejudice that the ancients were better informed about the times nearest to them than we are now. However, it is also believed that this was not so. For example, scholars of King Alfred's time knew very little about the origin of the Anglo-Saxons (COLLINGWOOD ROBIN J. 1996, 127). As we can see further, this remark applies directly to our topic.

Most evidence about the Alans was left by Ammianus Marcellinus. He, as well as some other historians of their time, believed that the Alans were the Massagetai of the past; however, no evidence for this was given. Inciting his description of the appearance of Alan, at some time, because of a translation error, a significant inaccuracy about their supposedly "somewhat slanting eyes" occurred (ALEMANY AGUSTI, 2000, 2.17.2 [21]), which led to what should be indicative of their Asian origin. In the Russian translation of Aleman’s work, this passage, obviously after reconciliation with Marcellin’s text, is presented in a completely different way: “If you don’t look fierce, it’s still formidable”. In the latest translation, Marcellin’s text was read as follows:

Nearly all the Alani are men of great stature and beauty; their hair is somewhat yellow, their eyes are terribly fierce; the lightness of their armour renders them rapid in their movements; and they are in every respect equal to the Huns, only more civilized in their food and their manner of life. They plunder and hunt as far as the Sea of Azov and the Cimmerian Bosphorus, ravaging also Armenia and Media. (MARCELLINUS AMMIANUS. 2009. BOOK XXXI. II, 21)

A certain similarity between the Alans and the Huns, noted by Marcellinus, is a consequence of a nomadic way of life. The Alans were the first to be subjugated by the Huns in Europe, and together they defeated the Ostrogoth tribal alliance in 375. The date of the Huns' invasion of Alanian land remains unclear, so it is not known what time period the Alans remained in close contact with them. Ammianus only writes that during the invasion of the Huns, many Alans were killed, and those who survived (mostly women) were included in their composition. In this case, one generation is enough for the defeated Alans to join the nomadic way of life. At the same time, the absence of a permanent residence and no similarity in the arrangement of carts or transport housing could be taken as a similarity. Moreover, Marcellinus could not know about the ideological differences between the Alans and Huns, which are usually reflected in the types of burials of the nomadic peoples. Research of Hun graves revealed a significant difference between them – some of them were kurgan burials and others were not. Because of this difference, it was concluded:

At the common unity of culture being material in all its ethnic components, researchers found traits marking ethnic differences in the types of burial structures. However, according to most experts, the union of Huns also had a complex multicomponent ethnic structure. This allows us to offer a version to explain the differences in the construction of burial structures (mound or no mound) which are just some ethnic differences of the population (IVCHENKO A.V. 2003, 46).

According to Marcellinus, the Alans occupied the territory from the Pontic steppes to the Vistula River in the northwest and the north-eastern shores of the Caspian Sea, but they penetrated farther to the east and southeast in separate groups. Perhaps the latter gave reason to separate the Alans into European and Asian parts, while Europe and Asia at that time were shared by the Tanais River (Don). Many other groups were also collectively called Scythians or Alans, following the dominant tribe, and at one time, the Alans were such a tribe, which follows from the words of Marcellinus:

Little by little, they (i.e., Alans – VS) subjugated neighboring tribes in numerous victories and spread their name on them, as the Persians did (MARCELLINUS AMMIANUS. 2009. Book XXXI. I, 13)

Among subjugated tribes were Neuroi, Melanchlainoi, Gelonians, Agathyrsians, and other tribes, previously mentioned by Herodotus, and the several ones that appeared later. The undoubted presence of the Turkic tribes among the Alans is shown by their completely Turkic names (Ιτιλησ, Αραβατησ, Thogay), and the ethnonyms Alans and Ases are still used to refer specifically to the Turkic peoples. For example, the Megrels, the neighbors of the Karachais, call them Alans, the Karachais and Balkarians use the term "Alan" when referring to the word "kinsman", "fellow tribesman" (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 268, 294).

Describing different peoples, Marcellinus often speaks about the peculiarities of their language, and from the texts, it is clear that he is well acquainted with the Persian language. However, he does not say anything about the Alan language. If they spoke one of the Iranian languages, he should have mentioned it. He simply says that the population of the Black Sea region, among whom he singled out the Jaxamatæ, the Mæotæ, the Jazyges, the Roxolani, the Alani, the Melanchlænæ, the Geloni, and the Agathyrsi, speaks different languages and has different customs (MARCELLINUS AMMIANUS. 2009. BOOK XXII, VIII, 31). The legend of friendship found in Lucian's dialogue "Toxaris" can give a certain idea of the relationship between the peoples who inhabited the shores of the Sea of Azov in Scythian times. It's a paraphrase after the English translation. (LUCIAN… 1913, 173-195) is offered below.

This Arsacomas, the son of Mariantes, was on a visit to Leucanor, king of the Bosporus, in connection with the delay in paying tribute to the Scythians. When the matter was settled, a banquet was held, at which the guests wooed the royal daughter Mazaea. Struck by her beauty, Arsacomas asked the king to give the daughter him as a wife. He declared that he would be a better husband for her than others when it comes to wealth and property. The king was very surprised by this, knowing about the poverty of Arsakom, and asked how many herds and wagons he had. Arsaсomas replied that he own no herds and wagons, but he had two noble friends, such as no other Scythians had. The answer caused ridicule among all those present. Leucanor preferred to give Mazeya to the leader of the Machlyans, Adyrmachus. He was to take his bride along Lake Maeotis to the Machlyans. Upon returning home, Arsakom told his friends Lonchates and Macentes about the scornful attitude of the king towards him. He was indignant at the fact that Leucanor had given his daughter to Adyrmachus only because he had a lot of different goods, as if heavy wagons and golden goblets were more precious than friendship, which is stronger than all his kingdom. Sharing the indignation of Arsacomas, Lonсhates replied that such humiliation concerns all three of them and must be given a worthy answer. He himself promised to give Arsakom the head of Leucanor, and Maсentes should bring him his bride. Let Arsacomas stay at home and gather horses, men, and weapons as much as necessary for a great cause. When everyone agreed with this, Lonchatws went to the Bosporus, and Macentes to Makhlyans, each on horseback. Remaining, Arsacomas began to gather an army according to the Scythian custom. The custom was that a person sacrifices a bull, butchers the meat and fries it, and spreads the skin on the ground. On this skin, he sits down, holding his hands behind his back, supposedly his hands are tied. This position means the posture of the petitioner. The person's relatives and those who are disposed towards him come up and take part in the sacrifice and, placing their right foot on the skin, promise any help that is in their power. The poorest offer at least their personal services. No troops can be more reliable and invincible than those assembled in this way. The act of stepping on the skin represents an oath. As a result, Arsacomas raised some 5,000 horses and 20,000 heavy-armed and light-armed foot soldiers together. Meanwhile, Lonchates, unknown to anyone in the Bosporus, came to the king and, on behalf of the Scythian society, filed a complaint against the Bosporan shepherds who invade the plain with their flocks, but shall graze only as far as away the stony ground. He also gave consent to the punishment of the Scythians, if they are caught as unauthorized cattle-lifters. After that, he proceeded to his own part and informed the king that soon a large army led by Arsacomas would invade the Bosporus. He explained the reason for this by the fact that the king refused him the hand of his daughter. Further, Lonchates explained to Leucanor that Arsacomas is not his friend and that he is held in higher regard by dignitaries and considered in all respects a better man. Lonchates promised to deliver the head of Arsacomas to Leucanor if he will give him his second daughter named Barcetis as a wife. Leucanor agreed to this but had to take an oath that he would keep his word. To do this, Lonchates offered to go to the sanctuary of Ares and there mutually swear behind closed doors without prying eyes. As soon as they entered there, and the guards left, Lonchates drew his sword and, holding the king's mouth with his left hand stabbed him in the breast. Then, cutting off his head, Lonchates left the temple. He hid his head under a cloak and said that he would return speedily, as he has been sent by the king to fetch something. Thus, he managed to get to the place where he left his horse, jumped on it, and galloped to Scythia. The promise to deliver the head of Leucanor to Arsacomas was fulfilled. The news of this reached Macentes when he was on his way to Mahlyans, and upon his arrival there he was the first to announce the death of the king. Macentes convinced Adyrmachus that, as a son-in-law of Leucanor, he was entitled to the throne and said: “Go there and state your claims while everything is still unresolved. For myself, I am an Alan and also related to Mazaea through the mother, since Masteira whom Leucanor married, was of our people. Macentes was able to say this because he wore the same dress and spoke the same tongue as the Alans. These characteristics are common to Alans and Scythians, except that the Alans do not wear their hair very long, as the Scythian do. Macentes added to his resemblance to the Alans by docking his hair and thus being able to pass for a relative of Masteira and Mazaea. Adyrmachus agreed and went to the Bosporus, trustingly leaving Mezeya in the care of Macentes. During the day, Macentes accompanied Mazaea in a wagon, but with the onset of darkness, he put her on horseback and, sitting behind, abandoned the path along the Meotian Lake, and went to the left of the Mitreya Mountains. On the third day, he completed the entire journey from Makhliena to Scythia, where he handed over Mazaea to Arsacomas. Adyrmachus, learning about the stratagem, did not continue his journey to the Bosporus, because the illegitimate brother of Leucanor Eubiotus, summoned from the Saurmatae, was already on the throne. Further events developed like this. Adyrmachus and Eubiotus with the Alans and Sauromatae combined their armies and advanced through the hill-country to Scythia. In the ensuing battle, the Scythians began to suffer defeat. Lonuchates and Macentes were wounded, the soldiers were already throwing away their weapons, but Arsakomas rushed to their rescue, which inspired the remnants of the army, and he himself killed Adyrmakh. Thus, what had been a defeat turned into a victory. The next day, a truce was signed, according to which the Bosporans pledged to double the tribute to the Scythians, and the Alans promised to atone for their guilt by subduing the Sinds, who had previously rebelled against the Scythians.

The name of Lonchates (Λογχατησ) can be translated as "a long-haired" (OE lang, Eng long and OE hād/hæd "hair") . OE maca "comrade, fellow traveler" which is included, according to Holthausen, in such Anglo-Saxon proper names as Meaca, Mackenthorp, Mackensen in such Anglo-Saxon names as Meaca, Mackenthorp, Mackensen (A. HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 209, 216) and OE ent "a giant" fit for the name of Macentes (Μακεντησ). The mention of long hair in the legend suggests that the proposed interpretation of the name Lonсhates is correct. This once again testifies to the presence of the Anglo-Saxons near the Sea of Azov. The fact that Lonchates and Macentes called themselves Scythians, as opposed to Alans, is not so important, because it is not known what meaning they attached to these words. After all, OE. scytere simply means a shooter, and the Greeks used this word as an ethnonym due to a misunderstanding. On the other hand, the Scythians and Alans, despite the common language, were opponents in the battle. Other facts of the legend also speak of the existence of hostility between them. All this only indicates the complexity of relations among the population of the Great Scythia, which may have both ethnic and political reasons. For us, the fact of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons is important there.

The presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe in Scythian times can be convincingly confirmed by the decoding of the epigraphy of the Northern Black Sea Coast and the then some realities by means of the Old English language. In this way The Alan-Anglo-Saxon Onomasticon was compiled, a small part of which is given below.

ακινακεσ (akinakes), a short, iron Scythian sword – OE ǽces "an ax" and nǽcan "to kill" suit well.

Αργαμηνοσ (argame:nos) – OE earg “cowardly”, mann “a man”.

Αριαπειθεσ (ariapeithes), the name of a Scythian king – OE ār „honor, dignity, glory” (ārian "to honor"), fǽtan „to decorate” (“adorned with glory”).

Beorgus, the Alanian king who invaded Italy in V century AD – OE beorg 1. "a mountain, hill", 2. "protection".

Γωαρ (go:ar), Alanian leader in Gaul at the beginning of the 5th century, several places in the west have the same name (BRAUN F. 1899, 98) – OE gear "protection, a weapon".

Ηλμανοσ (e:lmanos), Olbia, Vasmer – OE el “strange”, mann "a man".

Eochar, Alanian king in Armorica (north-west France) – OE eoh "a horse" and ār "a messenger, herald, apostle".

Ιδανθιρσοσ (idanthirsos), Scythian king – OE eadan "performed, satisfied” and đyrs "a giant, demon, wizard".

Ιεζδραδοσ (iedzdrados), Olbia – OE. đræd "thread, wire”, while the first part of the name semantic approach OE īse(r)n "iron, of iron".

Λικοσ (likos), the son of Spargapeithes – by OE līc "body" could be called a man of large stature.

Μαστειρα (masteira), the Alanian, the wife of the king of the Bosporus Leukanorus – OE māst "most", āre "honor, dignity."

Respendial, Alanian king in Gallia in early 5th century – OE respan "to reproach" and deall “proud, brave”.

σαγαρισ (sagaris), battle axe, the Scythian weapon – OE sacu "strife, war" and earh "an arrow".

Σαδιμανοσ (sadimanos) – OE sǽd "sated, satiated" and mann "a man".

Sangibanus, Alanian king in Gallia in the 5th c. – OE sengen "to burn" and bān "a foot, bone".

Σαυλιοσ (saulios), the son of Gnuros – apparently from OE sāwol "soul".

Σπαροβαισ (sparobais), Panticapaeum – OE spær "gypsum, limestone” and býan "to build" ("a mason, builder").

Τασιοσ (tasios), the Roxolanian leader at the end of the 2nd cen. BC – OE tæsan "to wound"

Φαδινομοσ (phadinomos), Tanaïs – OE fadian "to lead" and nama "name".

Φηδανακοσ (phedanakos), Tanaïs – OE fadian „to lead” and naca „a boot, ship”.

Φλιανοσ (phlianos), Olbia – OE fleon "to escape, avoid".

Scientific conscientiousness requires a quote from an author who has his own opinion on this issue:

… of the nine ancient, undoubtedly Alanian proper names to the west, only one name can be explained from the point of view of the German language, and even then with a stretch. This name is Eochar (BRAUN F. 1899, 96-97).

Brown could apologize for not knowing that Old English should be used for the decryption. With its help, it is also possible to decipher many ethnonyms of Scythian-Sarmatian times:

Αγαθιρσοι (agatirsoi), according to Herodotus, the tribe of the Agathyrsians – OE đyrs (thyrs) "a giant, demon, magician" is well suited for the ethnonym. For the first part of the name, we find OE ege "fear, terror", and the whole means "terrible giants or demons". However, OE āga "owner", āgan "to have, take, receive, possess" suit phonetically better. Then the ethnonym can be understood as "having giants". Below, we decipher the ethnonym the Thyssagetai (see Θυσσαγεται) as a nation of giants in the north of Scythia. Thus, we can suppose that the Agathyrsians subdued the Thyssagetai

Βουδινοι (budinoi) Boudinoi, rather, Woudinoi, the people who lived, according to Herodotus, in the country, overgrown with various trees – OE widu, wudu “tree, wood", Eng wooden.

Θυσσαγεται (thussagetai), the Thyssagetai, one of the folks in Northern Scythia mentioned by Herodotus, or Thyrsagetae (by Valery Flaccus) – the presence of the morpheme getai/ketai (Μασσαγεται, Ματυκεται, Μυργεται) in the names of several tribes is noteworthy. In addition, the Thracian tribes Getae (Γεαται) are known in history. We can suppose that this word means "people". The closest to it is the Chuv kĕtỹ "a flock, herd". Then Thyssagetai were "unruly people" (OE đyssa "rowdy”). If the form of Valery Flaccus is more correct, as it is likely, since it echoes the name of the Agathyrsians. (see Αγαθιρσ, Αγαθιρσοι). Then the Thyrsagetae means "the people of giants and wizards" (OE. đyrs "a giant, demon, wizard").

Μελαγχλαινοι (melankhlainoi), the Melanchlaeni – Herodotus places Melanchlaeni to the north of the Royal Scythians and explains their name as "dressed in black" (Gr. μελασ "black"). In fact, Melanchlaeni is an Old English name, as ancient Angles had a proper name Mealling, originated from OE a-meallian "to get furious" (see HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 216), which together with OE hleonian "to protect" was used by the newcomers for calling their relatives. One might think that they were particularly militant.

Νευροι (neuroi), the Neuri – the people standing second after Agathyrsians in Herodotus' list – Herodotus indicated that they left their homeland and settled among the Budinoi. (IV, 105). OE neowe, niowe means "new". The nominalization of the word could give neower "a newcomer". The Anglo-Saxons could not call themselves newcomers; it is assumed that such a name could be given to a new group of tribesmen by local settlers, ie, the Anglo-Saxons, who came here earlier.

Σκυθαι (skythai), the Scythians – OE. scytta "a shooter". The Scythians were considered the best bow-shooters, and the ethnonym "Scythian" was considered a synonym for the shooter. The idea of the Germanic origin of the word has long been mentioned by V.I. Abaev: "Gmc. *scutja is an ideal etymon for σκυθασ" (ABAYEV V.I., 1965: 21).

Having so much evidence of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Ukraine during the Scythian-Sarmatian time, which is also confirmed by separate lexical matches between the Old English and Slavic languages and the participation of the Anglo-Saxons in the creation of the Rostov-Suzdal Principality (see the sections Anglo-Saxons in East Europe, Anglo-Saxons at Sources of Russian Power ), consider how they might be connected with the Alans.

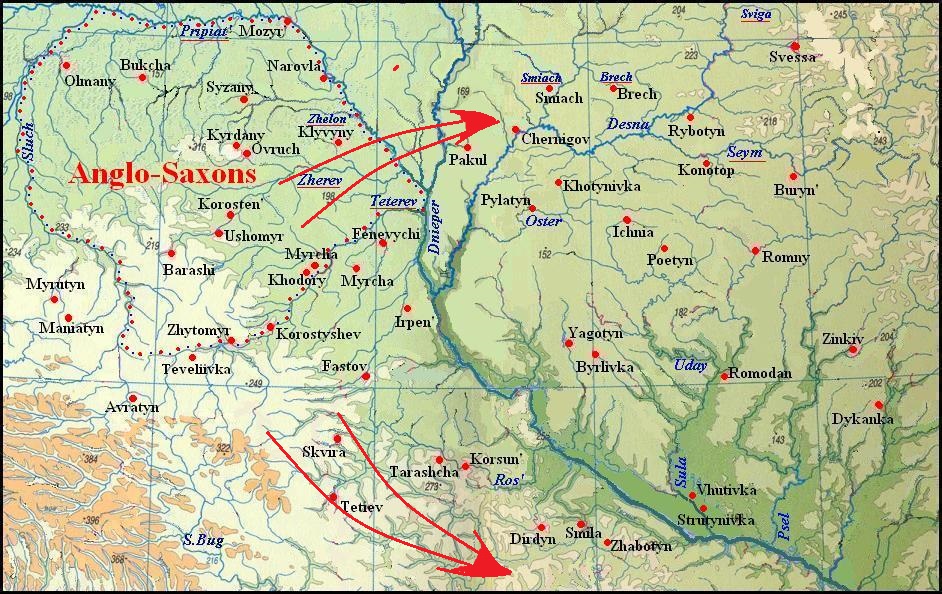

The Urheimat of Anglo-Saxons found by the graphic-analytical method, was located on the ethno-producing area between the Sluč, Prypyat’ and Teteriv Rivers (it is marked by red dots on the map at left). This area is divided into three roughly equal parts by the Uzh and Ubort Rivers. It can be assumed that in these subareas, close German dialects formed, the speakers of which were three separate ethnic units.

Place names, which cannot be deciphered by Slavic languages, but can be deciphered using Old English and Old Saxon, in doing so, not only confirm the localization of the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons but also indicate their presence in continental Europe for a long time and sometimes graphically depict the migration routes. During the long search for the toponyms of Anglo-Saxon origin, more than four hundred were found (see the map Google Map below). This topic is discussed in more detail in the section Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe, some of the most convincing examples from the general list are the following:

Avratyn, a few villages in Right-Bank Ukraine – OE ǽfre "after, constant", tūn "village".

Boriatyn, villages in Lviv and Zhytomyr Regions of Ukraine, Briansk and Tula Regions of Russia, Bariatino, the administrative center of Kaluga Region, Russia, Boratyn, villages in Lviv, Volyn, Rivne Regions of Ukraine – OE bora "a son", tūn "village".

Burtyn, a village in Khmelnytsk Region – OE būr "a peasant", tūn "village".

Delatyn , a town in Ivano-Frankivsk Region – dǽl, dell "valley", tūn "village".

Irpen', a river, rt of the Dnieper – OE ear 1. "lake" or 2. “ground”, fenn “bog, silt”, could mean “sludgy lake” or “boggy ground”.

At right: The Irpen' River.

The photo from the site Foto.ua

Khotyn, a few towns and villages with this or with a derivative of it in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Poland – OE. hof “court, area”, tūn "village".

Konotop, ten towns and villages in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Poland, and a few derivatives of it – OE. cyne- «royal», topp "a top".

Korsun, several villages and rivers in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus – OE cors "reed".

Kyrdany, a village in Zhytomyr Region – OE cyrten, "nice".

Mius, a river flowing in Sea of Azov – OE mēos "moss, swamp".

At left: The Mius River

Photo of Оlga GOK. Rostov on Don.

Myrutyn, a village in Khmelnytsk Region and the village of Myrotyn in Rivne Region – OE mūr "wall", tūn "village";

Resseta, a river, rt of the Zhizdra, lt of the Oka – OE rǽs "running" (from rǽsan "to race, hurry") or rīsan "to rise" and seađ "spring, source".

Rikhta, a river, lt of the Trostianytsia River, rt of the Irsha River, lt of the Teteriv River, rt of the Dnieper and a few villages in Kyiv and Khmelnytsk Regions – OE riht, ryht “right, direct”;

Romodan, a town in Poltava Region – OE. rūma „space”, dān "humid, humid locality".

Seym, a river, lt of the Desna River, lt of the Dnieper – OE seam "side, seam";

Werhulivka (Vergulivka), a village in Luhansk Region – OE wergulu "nettle”.

Wolfa, a river, lt of the Seym River, lt of the Desna River – OE wulf “wolf”.

Wytebet', a river, lt of the Zhizdra, rt of the Oka – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, river-bed".

Yagotyn, the town in Kiev Region – OE iegođ „a little island”.

Anglo-Saxon place names in Continental Europe

On the map, Anglo-Saxon place names are indicated by red points. The settlements of Markovo, Markino, and similar have a violet color.

Red space marks the Urheimat of the Anglo-Saxons.

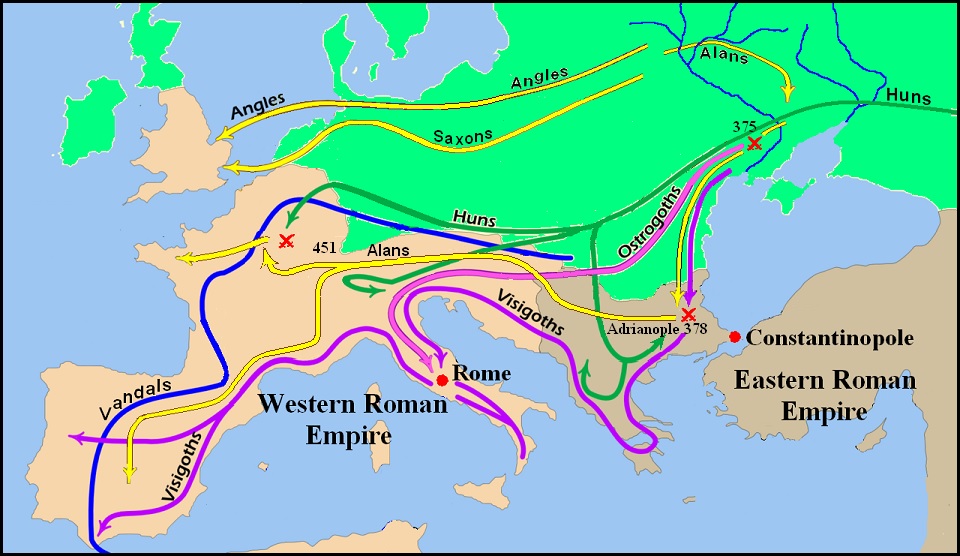

The red asterisks mark the battlefields at Adrianople (378) and on the Catalaunian Plains (451) where the Alans took part.

Having found in the above list the names of several Alanian leaders (Αρδαβουριοσ, Beorgus, Γωαρ, Eochar, Μαστειρα, Respendial, Sangibanus, Τασιοσ a.o.), we can assume that the Alans were in fact either related to the Anglo-Saxons or a part of them. Most likely, the latter should be accepted, since there are grounds to consider both the modern Ossetians and the Turkic peoples of the Caucasus as the descendants of the Alans, then, given the recognized diversity of the population of the Northern Black Sea region, there is no other way out, how to agree that a tribal union was hidden under the common name Alans in which the Anglo-Saxons played the main role. It should be borne in mind that identification with "prestigious" ethnos by individuals or groups of people, without even adopting its language, is a widespread phenomenon even in our time. The Anglo-Saxons could play a major role in this alliance, and the ancestors of the Ossetians were the only members of the union. An explanation of the dominant position of the Anglo-Saxons in this tribal alliance is that a part of them occupied an area in the Donbas, which was rich in deposits of copper ore. Copper smelting and the fabrication of everyday objects for use allowed them to gain an economic advantage over the population of other ethnicities in the Northern Black Sea, and as a consequence, political dominance:

New archaeological materials allow us to say with confidence that in the Donbas, at least in the Late Bronze Age, there was a large mining and metallurgical center, where not only ores were mined, copper was smelted, but also neighboring territories were supplied with manufactured tools, metal, and ore. As rightly noted by E.N. Chernykh, the localization of copper deposits allowed the tribes that developed them to get a new powerful source of enrichment, and thanks to their own metal, mining and metallurgical centers subordinated vast territories to their influence. (TATARINOV S.I. 1977: 206).

S.I. Tatarinov writes about the Late Bronze Age, but this is a general pattern, as evidenced by his reference to E.N. Chernykh. There is a variety of evidence, including onomastic evidence, that the Anglo-Saxons achieved political dominance in Scythian times. This topic is discussed in the sections "Royal Scythia and its Capital" and "The Ethnic Composition of the Population of Great Scythia According to Toponymy.". On the one hand, the name of the copper mine can be easily deciphered using Old English, while on the other hand, descendants of the Anglo-Saxons may have owned some surnames of the nearby population, which, when deciphered using the same means, reveal their social status ("customs officer," "merchant," "small trader," "tribute collector"). Surnames cannot reflect the entire structure of a particular Scythian political-economic entity; they only testify to its complexity. Its leader must have been a person with a specific title. V.I. Abayev, considering the Ossetian word äldar "lord", "prince", wrote:

One of the early Alanian paramilitary, semi-class terms… The impression that the military organization of the Alans made on the neighbors contributed to the penetration of this word into Hungarian and Mongolian (ABAYEV V.I. 1958: 126-127).

Abaev derived this word from OS. arm "arm" and dar "hold". In fact, it corresponds to Old English ealdor "prince," "lord," "king," which derives from Old English eald "old, elder." The term for leaders of Anglo-Saxon origin corresponds to the primacy of the Anglo-Saxons in intertribal formations, since the definition of "royal" corresponded to the dominant tribe. Not only were the Scythians "royal," but the Sarmatians as well.

J. Harmatta believes that the peak power of the Sarmatians occurred in the last quarter of the 2nd century B.C. and the first half of the 1st century B.C. (HARMATTA J., 1970, 39). Under conditions of stability, the development of trade, ways, and means of communication had resulted in different ethnic groups that began to appear in the Black Sea steppes at the beginning of the 1st millennium A.D. They were included in the tribal alliance of the Alans. Historians conclude the possibility of a warlike tribe ruling/controlling the masses of the population, ethnically alienating them:

Ethnic diversity and flexibility, cultural exchange, often over long distances, long-range policy, and regional differences occur, becoming ever more apparent in the study of steppe empires. The understanding of modern social anthropology, that the early medieval people consist of different groups which gather around a relatively small core, and soon began to feel attached to it, is confirmed (POHL WALTER, 2002: 3).

When the Goths came to Scythia, they learned that in the language of the local population, this country is called Ojom (Oium) (JORDANES. 1960: 25). Judging from the context, the area Oium was on the Left Bank of the Dnieper. This area can be associated with two place names having the same name, Izium, which is phonetically similar to the Chuvash combination of words ĕç “work” and um “plot, lot”. One of them, recorded on old maps, was located near copper mines, which were exploited already in the Bronze Age and have survived to our time under the name Kartamysh corresponding to OE ceart "wasteland, wild public land", myscan "to deform". There is reason to associate “Royal Scythia” with this territory (for more details, see Royal Scythia.)

The common origin helped the Alans to establish friendly relations with the Germanic tribes of the Goths, Vandals, and Suebi. Obviously, the natural Germanic ethnopsychology helped them quickly find mutual understanding with the Goths and Vandals than with other peoples. In 378, the Alans, in alliance with scattered Gothic detachments under the overall command of the leader of the Visigoths Fritigern, participated in the defeat of the Roman army near Adrianople.

The Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Alans migrated under the pressure of the Huns in search of new lands for settlement. They have not moved a single stream, but each of these people in their own way and only temporarily united for military purposes. Even the Alans, moved out at least in two groups, making it difficult to establish their migration routes. As always, during the migration of peoples, their way has been marked by settlements, where a part of the migrants remains to stay for various reasons. This phenomenon was observed by the ancient migrations of the Bulgars, Cimbri, Angles, and Saxons. The trail of the Alans to Adrianople is marked by the cities of Bulgaria Varna (OE wearnian "to warn, be careful") and Burgas (OE burg "borough"). The chain of place names that may mark the path of further movement of the Alans after Adrianople consists of the following:

Haskovo, a village in southern Bulgaria – OE hassuc "wet, row grass", Eng. hassock. Better OE has "hot", cofa "cave". There are hot springs in this area.

Rashkovo, a village in Sofia Region, Bulgaria – OE. ræscan "to tremble, swing". Most likely the Old English word had another meaning, as it does in its related Old Norse raska, which is translated as both "to tremble", and as "to rock", "to displace". This meaning is much better suited for the names of settlements of migrants. Cf. Raška, Raškovići, Raškovci.

Berkovitsa, a town in Montana Province, Bulgaria – OE berc "birch".

Raška, a town, the center of Rashka district in Serbia – see Rashkovo

Sige, a village in the municipality of Žagubica, Serbia – OE sige 1. "lowland", 2. "victory".

Raškovići, a village in the municipality of Goražde, Bosnia and Herzegovin – see Rashkovo

Berkovica, a village in Bosnia and Herzegovina – OE berc "birch".

Raškovci, a village in the municipality of Doboj, Bosnia, and Herzegovina – see Rashkovo

Vinkovci a city in eastern Croatia – OE wincian "wink".

Valpovo, a city in eastern Croatia – OE hwelp(a) "whelp".

Szekszárd (Szekszárd), a city in Hungary, the capital of Tolna county – OE sex, siex, "six", eard "land, place, settlement".

However, judging by the density of the Anglo-Saxon toponymy (see Google Map above), most of the Alans first moved to the Carpathian Mountains, and then, after crossing the Carpathians, advanced to Transylvania. This path among others is marked by the following place names:

Rakhiv, a city in Trancarpathia – OE. raha "chamois".

Bârsana, a village in Maramureş County, Transilvania, Romania – OE. bærs, bears "perch".

Rohia, a village in Maramureş County, – OE. raha "chamois".

Brad, a city in Hunedoara County in the Transylvania region – OE. bræd "width".

Arad, the capital city of Arad County, Romania – OE. ared, arod "quick, rapid".

A further way of the Alans, through the territory settled by Germanic tribes, is difficult to trace because of the similarity of local dialects to Old English. However, it is known that the Alans together with the Vandals and Suevi reached Spain, where they founded their kingdom, and after the destruction of the kingdom by the Visigoths, they along with the Vandals crossed into North Africa. The kings of the newly created kingdom here officially called themselves the kings of the Vandals and Alans (BRAUN F. 1899: 96). This state pursued a too-aggressive foreign policy and existed only until 534, falling under the blows of Byzantium.

While driving through France, the Alans also founded their settlements and their way to Spain across southern France can be marked as follows:

Bourg-en-Bresse, a commune, the capital of the Ain department,– OE burg "borough, town", bræs "ore, bronze".

Lyon, a city in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region – OE lion "to lend", "to preserve".

Lemps, a commune in the Ardèche department – OE. limpan "to belong", "to be fit".

Gignac, a commune in the Hérault département in the Occitanie region – OE. geagn "against", gegn "right".

At left: Alanian kingdom in Spain.

The Alanian kingdom existed in Spain for a short time (409-426), but Alanian presence here is reflected in a few place names, using the Old English language for decryption, for example:

Alenquer, a municipality in the Oeste Subregion in Portugal – there is an explanation of the name as "Alanian temple" involving OG kerika "church". Visigoths can give the name, but this word is not fixed in the Gothic language, and there was in OE cirice "a church".

Burgos, a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León – OE burg "borough".

Galisteo, a municipality within the province of Cáceres in Extremadura – OE gāl "joyful, cheerful', eace "multiply, increase", đeo "servant."

Huesca, a city in the autonomous community of Aragon – OE wæsce "washing place".

Lisbon, the capital of Portugal – OE liss (liđs) "grace, love", bōn "entreaty”. Liss as a part of the name is present in many other place names in France, Netherlands, and Britten.

Logroño, the capital of the province of l Rioja in Spain – OE lōg “place”, rūne “with”.

Logrosán, a municipality within the province of Cáceres in Extremadura – OE lōg "place", reosan "a plant" (?).

Madrid, the capital of Spain – the first mention of the city is preserved in the Arab transcription: مجريط (Majrīṭ, pronounced as maʤrit). There are several versions of the origin of the name, but we can substantiate an Alanian origin: OE māg "bad, shameless" and rīđ "a stream, river". Madrid is located on the small Manzanares River.

Murcia, a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital of the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia – OE murcian "be unhappy, complaining".

Odrinhas, a locality near Madrid – OE eodor "hedge, surround, enclosure", inn "dwellng, house."

Rascafría, a municipality of the Community of Madrid – OE ræsc, ME rash "nimble, quick, vigorous", frea "lord, king".

Salamanca (Salamanca), a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León –OE sala "sale", mangian "trade".

Utiel, a municipality in the comarca of Requena-Utiel in the Valencian Community – OE ūtian "to banish, steal".

Some evidence of friendly relations between the Alans and Goths provides also archaeology. While the Slavic tribes of the Zarubintsy culture were displaced by the Sarmatians from the Forest-steppe Dnieper Land between the rivers Tyasmyn and Stugna, "the relation the Sarmatians and the bearer of the Cherniakhiv culture in the 2nd-4th centuries was totally different than the situation between the Sarmatians and Zarubintsy people". The Sarmatians were involved in the creation of the south-western region of the Cherniakhiv culture, and their funerary rites are like Chernyakhiv ones (BARAN V.D., Otv. Red., 1985: 9-10). The Chernyakhiv culture was created by the Goths who came to the Black Sea but its cultural Sarmatian traits were superstrate, "that is, they are superimposed on the already established culture in the process of its spread to new territories" (GUDKOVA O.V. 2001:39). In this connection, we can assume that the cultural interaction of the Goths and some part of the Sarmatians was due to the similarity of their languages and customs preserved since the Germanic community.

Taking all this into account, we must make the final conclusion that the German-speaking Alans could only be that part of them that during the Great Migration period went to Central Europe, and then to Spain and Africa and, as it turned out, even to the British Isles. In other words, under the common name of the Alans, both Germanic-speaking and Iranian-speaking and even Turkic-speaking tribes of the Northern Black Sea region should be hidden, the reason for which could be the transfer of the name of the dominant tribe to other participants in a voluntary or forced union of multilingual tribes.

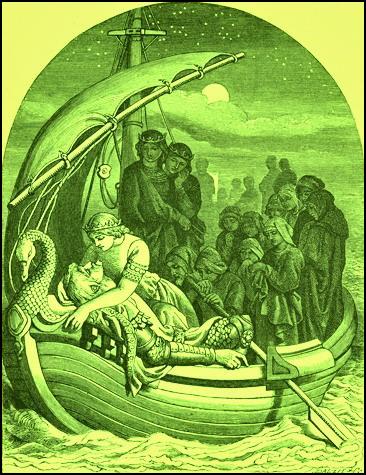

Quite recently, the long-known connections between the cycle of legends about King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail with the Scythian-Sarmatian world have been summarized. In 2000, a book was published wherein authors try to explain these relationships (LITTLETON C. SCOTT, MALCOR LINDA A. 2000). One of these connections was noticed as one of the first, and later Dumezil recalls it. In the multinational epic of the peoples of the Caucasus about the Narts, a described episode of the death of one of the heroes named Batraz has a parallel to the death of King Arthur. Both die from the fact that their swords are thrown into the water.

The one illustration of the book "From Scythia to Camelot": Morte D'Arthur by Daniel Maclise

The book was controversial in the scientific world, as evidence of the authors is based on analogies which can be not so convincing. The reasons for these connections in influencing a small number of the Iazyges who served in the Roman legions during their campaigns into Britain in the 2nd century on the culture of the indigenous Celtic population look unconvincing too.

The Celts, hostile to the Romans, could not have close cultural contact with them, the more it is doubtful that they were subjected to the cultural influence of the Iazyges. According to archaeological data in the Ribchester area, a small Sarmatian community existed there for several centuries (ibid., 19), which implies that the Sarmatians were not assimilated among the local population and therefore did not have a great cultural influence on it without having close contacts with them. The artifacts of the Sarmatian type found cannot say anything about this. In addition, they have never been to the Northern Black Sea region and do not belong to the Sarmatian cultural circle, their settlements were located on both banks of the lower Tisza. (see Cimmerians)

The Sarmatian cultural influence could have been made by numerous new migrants, namely by the Alans, who undoubtedly had common cultural elements with the Iranian-speaking population of the Northern Black Sea Coast, but historical data on the relocation of the Alans to Britain are absent. Although Linda Malcor explains the name of Lancelot, one of the knights of King Arthur, as “(A)lan(u)s à Lot” (Alan of Lot, the area in Southern Gaul, where at one time massed Alans). One would assume that other Alans came to Britain with Lancelot.

By the way, there is no generally accepted interpretation of the name Arthur: The origin of his name is still a puzzle, though many proposals have been made (ZIMMER STEFAN. 2015: 131). The German linguist believes that the name may be native Latin, epichoric from Dalmatia, or Celtic (ibid: 132). However, if the history of the Anglo-Saxons goes back to Scythian times, then this name may have been brought to Britain by the Alans, who borrowed it from the Scythians. In this case, to understand the meaning of the name, it is necessary to bring Chuv. ar "man", and tură "god", "deity". Arthur's name echoes the name of his court adviser, Merlin, which goes back to Welsh. Myrddin and means "man of faith" (cf. Kurdish mēr "man", dīn "faith"). The Kurdish language is used because the Cimbri-Kurds, after adventuring on the continent, moved to Britain and had a great cultural influence on the local Celts Cimbri-Cymry). Since the name Arthur is well deciphered using the Chuvash language, the names of some knights of the Round Table may have the same origin. For example, to decipher the name Percival, you can use Chuv. pĕr "whole, full", syvă "healthy", which together with the affix –lă can form the word meaning "husky, sturdy".

If the Alans arrived in Britain from Southern Gaul, the more they could do it even more easily from Northern Gaul. It is known that Flavius Aetius, the honored leader, the actual governor of Gaul, is known for his victory over the Huns on the Catalaunian Plains in 451 near the city of Châlons-en-Champagne, gave the Armorica area (north-west France) into the possession of Alanian King Eochar (otherwise Goar). It is known that Eochar, with a part of the Alans, did not follow King Respendial to Spain and stayed in central France.

Invasions of the Roman Empire by Goths, Huns, Vandals, and Anglo-Saxons in 4-6 centuries AD

In the subsequent time, there were several rulers named Alan in Armorica, and, in addition, the local place names testify that the peninsula of Brittany and the adjacent area were inhabited by the numerous Alan horde:

Brest, a city in the Finistère département in Brittany – OE. breost "breast".

Kerlouan, a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany – OE. ceorl "man, peasant", own "own".

Landéda, a commune in the Finistère department – OE. land "land", ead "wealth, happiness".

Landerneau, a commune in the Finistère – OE. land "land", earnian "earn, win, gain".

Landivisiau, a commune in the Finistère – OE. land "land", eawis "apparent".

Locarn, a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department of Brittany – OE. loc "lock", ærn "house".

Rostrenen, a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department of Brittany – OE. rūst "rust, red", ren "house".

A chain of place names (deciphered by the use of the Old English language) stretches from the battle area of the Katalaun fields to this cluster of place names. It includes the following settlements: Sézanne, Bernay-Vilbert, Rambouillet, Brou, Berne-en-Champagne, Laval, Cornillé, and Rennes. Significantly, the name of Rambouillet is deciphered by Old English as "sheep's wool" (OE ramm "ram", wull "wool"). The local population has long been engaged in sheep breeding here, and subsequently, there was created a royal sheepfold was created where a fine-fleeced sheep rambouillet breed was bred.

English monk Bede the Venerable, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, asserted that the tribes of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes arrived in Britain in the 5th century after Roman legions left it. He reports the names of such leaders as Angles Hengist and Horsa (BEDE, XV), which can be translated from Old English as "a stallion" and "a horse". These names are suitable for horsemen, the Alans. However, the inhabitants of Jutland, from where, according to Bede, Angles came, were not riders but also other Germanic people were also there. The Bede described these events after nearly 150 years and used scant data about the ancestral home of the Angles from the Roman historian Tacitus (ca. 56 ca. 117 A.D.).

There is in the English county of Oxfordshire on a hillside near the town of Uffington, a strange figure by length of 110 m and in the form resembling a horse. The mysterious figure is made by filling ditches with broken chalk; its origin is unclear. The prevailing view is that the figure is of Celtic origin and this is proven, among other things, by the similarity of the strange head of the figure to images on Celtic coins of the first cen. AD. However, with careful study, it turned out that there is an overlap of two different figures – a horse and a dragon (or a snake) (BOTHEROYD SILVIA und PAUL F. 1999: 416). It can be assumed that the original figure of the dragon was later turned into the figure of a horse. It is not excluded that this was done during the reign of King Alfred the Great, as is also supposed. In this case, the figure could be modernized by Alan's riders, who had the horse as a symbol of worship borrowed from the Iranians (who were a part of the multinational Sarmatian alliance).

Uffington White Horse. Photo from Wikipedia.

There is much other scattered evidence of the Sarmatians in Britain, as well as hypotheses about how they got there. Especially, many artifacts of alleged Sarmatian origin are stored in museums dating back to Roman times. This topic is actively pursued by Giuseppe Nicolini from the University of Milan (Italy).

In principle, the similarity between the ethnonyms of the Angles and the Alans can indicate their common origin. The name of the tribe of the Ρευκαναλοι (Reukanaloi) (i.e., the "Light" or "Wild" Alans) suggests a possible metathesis in the word Alan. If n in this ethnonym sounded like ng (ŋ), then the transformation of "Angl" in "Alan" would be quite possible (angloi → aŋloi → alŋoi → alanoi). This explanation assumes the German origin of the word.

The German tribe of Anglii has been known since Tacitus' time. The preferred etymological theory deduces this name from *angula “hook", supposedly because the country inhabited by them had a curved shape. Another theory, namely the Turkic origin of the ethnonym, is more suitable in terms of semantics. Old Turkic oğlan (ohlan) "a son, boy, young man" had another meaning, namely, "a rider" (Chuv. dial. yulan "a horseman"). The name of the light cavalry (Pol. ułani, Eng. Uhlans) has arisen from this Turkic word. This plausible explanation encounters phonetic difficulties, overcoming which is tentative. The root oğ is represented in Turkic languages by only a few derivative words, but by itself has no sense. We can assume that it is a variant of the root oŋ (oŋğ) having several meanings – "a pat", "right", "light, convenient", "to improve ", i.e. oğlan originally could exist in the form oŋğlan and it gave angl- and alan-. Attempts to connect the ethnonym Alan with the Turkic oğlan have been known for a long time, but they are considered questionable (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 73), for some reason unknown.

The Anglo-Saxons, having moved to the left bank of the Dnieper, were in close contact with the Iranian tribes for quite a long time and could participate in the formation of a common cultural environment. It is difficult to say how much they were involved in this process, but the elements of the Sarmatian culture were assimilated by them and, having turned into Alans, they brought them to Britain. In the north of France, in the Calais area, there are several place names deciphered using the English language: Berck, Bernay-en-Ponthieu, Rambures, etc. The distance from here to the island of Britain is only one step, not without reason, the name of the Passa de Calais, which separates it from the mainland, is translated from French just so. In good weather, the Alans could repeatedly safely cross the island long before the invasion of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. When the Vikings began their predatory attacks on Normandy in the 9th century, it was already populated by people speaking the French language, because by the middle of the 10th century they had adopted the religion and language of the French (SAWYER PETER. 2002: 11), that is, the Alans were absent there. William the Conqueror went on a campaign from the mouth of the Somme River near Calais. It is not to exclude that the Angles and Saxons also might have used this same way. Still, a sea voyage from Jutland to Britain for people who did not have a long tradition of navigation would be a very risky venture.

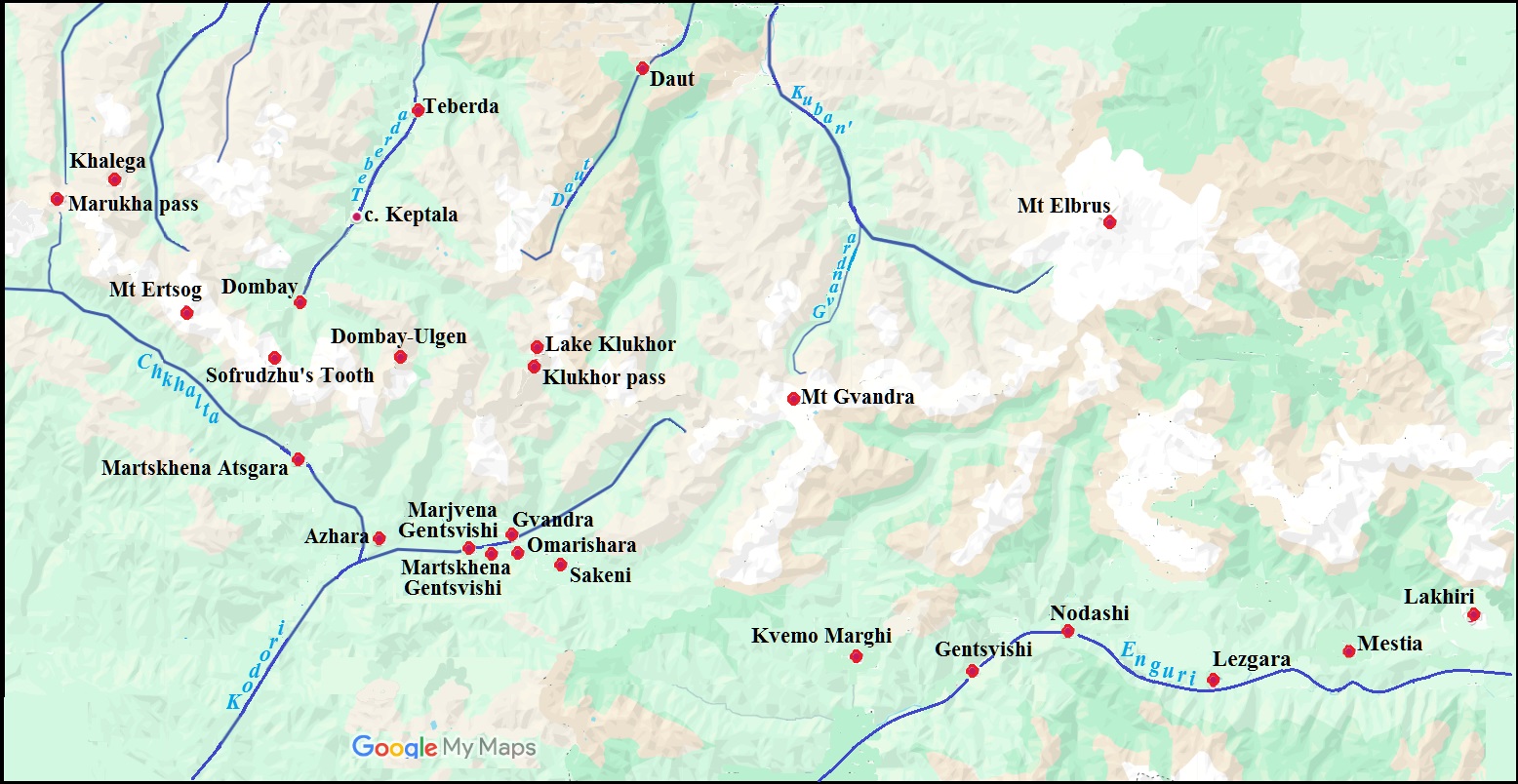

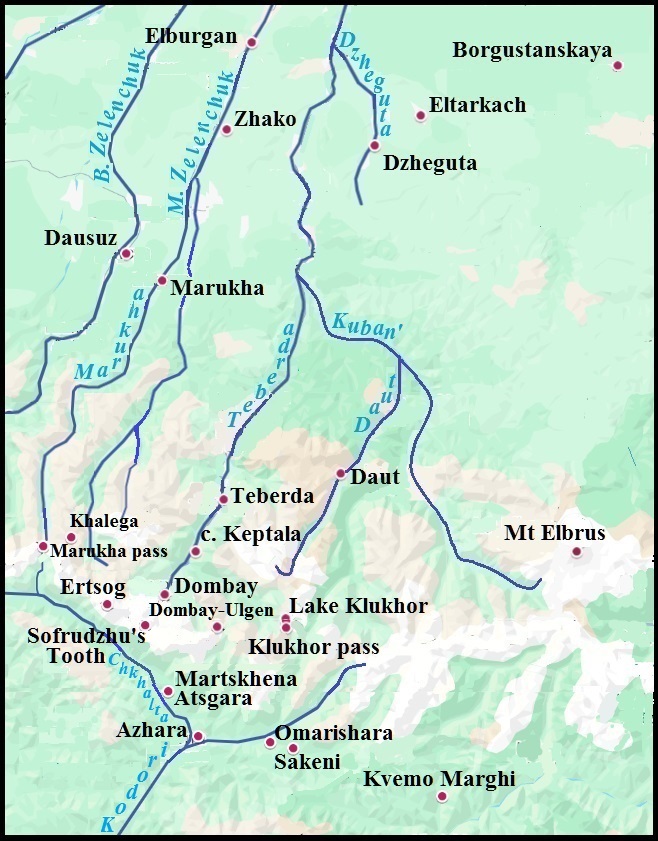

Of course, a part of the Alans remained in the North Caucasus, and this is evidenced by local place names (see the map at right).

Righ: Anglo-Saxon place names in the Azov region and the North Caucasus.

Place names mark the path of the Alans from Donbas to the foothills of the Caucasus and their settlement in Caucasian Alania. The most convincing examples are given below:

Yeya, a river flowing to the Azov Sea, and the original name is OE ea "water, river".

Sandata, a river, lt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don River – OE. sand "sand", ate "weeds".

Bolshoy and Malyi Gok (Hok in local pronunciation), rives, rt of Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don – OE. hōk "hook".

Sengileevskoe, a village in Shpakovski district of Stavropol Krai – OE. sengan "singe", leah "field".

Guzeripl' (Huzeripl' in local pronunciation), a settlement in the Maikop municipal district of the Republic of Adygea – OE. hūs "house", "place for house", rippel "undergrowth".

Baksan, a river and a town in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE. bæc "back", sæne "slow".

Mozdok, a city in North Ossetia and villages in the Kursk and Tambov Regions – OE. mōs "food", docce "sorrel".

Zelenchuk, two hamlets in Krasnodar Krai, a village in Karachay-Cherkessia, and six rivers in the North Caucasus having this word in their names – OE selen "tribute, gift", *cūgan "oppress" restored from the personal name Сūga which Holthausen associates with Icl. kūgan "tyranny", kūgi "oppressor" [HOLTHAUSEN F. 1074: 62].

Klukhor pass, a pass on the Voenno-Sukhumi road at an altitude of 2781 m through the Main Caucasian Range – OE hlǣw, hlāw “hill”, “mountain”, horh “dirt”, “mucus”.

Mount Elbrus, mountain peak in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE äl "awl", brecan "to break", bryce "fracture, crack", OS. bruki "the same", , k assibilated in s. Elbrus has two peaks separated by a saddle.

Elbrus

Photo by the author of the essay "My trip to Elbrus"

In general, the distribution of Anglo-Saxon place names in the North Caucasus corresponds to the territory of Caucasian Alania in the basin of the two Zelenchuk rivers (see map below). Procopius of Kessaria, the first to mention the Alans in the Caucasus, indicated that in the west their neighbors were Zegii or Zygians (Fr. Zigues on the map), Abasgoi or Abasgians (Awaz on the map).

Continuing to play a leading role in the political life of the Black Sea region, the Anglo-Saxons united in one state forming the entire population of the North Caucasus, which gave rise to the Khazar Kaganate (see Khazars). The name of one of the rulers of this state, Sarosios (512? – 596), can be deciphered with the help of OE. searo "skill, craftsmanship". On the ruins of the Khaganate, Caucasian Alania arose, about which the Hungarian monk Julian left some information. He visited it in 1235 during the search for the ancestral home of the Hungarians on behalf of the Hungarian king Bela, moving from the city of Matrika in the country of Sykhia on the western slopes of the Caucasus:

… the inhabitants (of this country – VS) represent a mixture of Christians and pagans: how many towns, so many princes, of whom no one considers himself subordinate to another. Here is the constant war of a prince with a prince, a small town with a town: during the plowing, all people of one place armed together go to the field, together mow, and then on the adjacent space, and in general coming out of their settlements for the cutting of firewood, or for whatever work, they all go together and armed, and in a small number they cannot go out safely from their settlements (GARDANOV V.K. 1974: 33)

It is clear from the description that there was no tribal alliance or the leading tribe in Alanya that can be spoken of. If there were Anglo-Saxons in these places, then they would have existed in very small numbers. William Rubruk, sent by King Louis IX, was ambassador to Mongolia in 1253. He met with the Alans in the Crimea and noticed that they are called there the Aas (RUBRUK WILHELM de, 1957: XIII). He also noted that the Alans do not drink Kumys, from which it can be concluded that they were not Turks, as Kumys is their national drink (Ibid: XII). Furthermore, he sometimes mentions the Alans on the North Caucasus and, in particular, notes that they were excellent blacksmiths. Alans could learn the blacksmith's craft during their stay in the Donbas.

Distribution map of "Alan" antiquities

according to [Zuckerman C. 2005: 72, Fig 1].

The location of the territory of Alania, highlighted in red on the map, is confirmed by the accumulation of Anglo-Saxon place names on it (see below). Interpretation of toponyms using Old English:

Borgustanskaya – OE beorg "mountain", west “west'.

Dausuz – OE deaw “dew”, swǣs “trusted, special, dear, loved”.

Daut – OE deaw “to dew”, -ed is the Past Participle suffix.

Dombay – OE dumb “dumb”, ā “always, forever”.

Dombay-Ulgen – OE dumb “dumb”, wealg “tasteless, bland, disgusting”.

Dzheguta – OE ge- is a prefix (with, together), gyte “downpour, flooding, pouring”.

Elburgan – OE el ”foreign, alien”, beorg "mountain".

Eltarkach – OE el “foreign, alien”, tear “tear”, ceace "cheek".

Ertsog, a mountain – OS herro “lord”, tiohh "gang, troop".

Keptala – OE ceap “buying, selling, trading”, tala, tela “well, appropriate, right, very”.

Khalega – OE hāleg, hǣlg “holy”, ea "water, river".

Klukhor – OE hlǣw, hlāw “hill”, “mountin”, horh “dirt”, “mucus”.

Kuban’ – OE kū “cow” bān “bone”.

Marukha – OE mearu "tender", "soft", ea "river".

Sofruszhu, the mountain, its peak, resembling a bird's beak, is called "Sofrudzhu's Tooth" – OE seo “pupil”, frio free, noble”, giw "vulture”.

Teberda – OE đōhe “clay” beorht “glittering”.

Zelenchuk – OE selen “tribute, gift” cūgan “oppress”.

Zhako – OE geac “cuckoo".

Working, several toponyms of presumed Anglo-Saxon origin were discovered on the southern slopes of the Main Caucasus Range. They formed a chain along the banks of the Chkhalta River and the upper reaches of the Kodori River. Apparently, under pressure from the Karachays, some Alans crossed the Marukha Pass and descended the Marukha River into the Chkhalta Valley. Moving further, they reached its mouth and crossed into the Kodori Gorge. This route is marked by the following chain of toponyms, decipherable using Old English:

Martskhena Atsgara – OE āge “property. possession", gāra "foothills". Martskhena from Geo. მარცხნივ "left".

Azhara – OE āge “property. possession", āre “honor, grace, favor"; "propriety, privilege".

Kodori – OE codd "pod" ōra "bank".

Marjvena and Martskhena Gentsvishi – OE a-cwencan “to extinguish, vanish", wīsce "meadow". Marjvena from Geo. მარჯვენა "right".

Gvandra, a mountain and village – OE ōm/ōme “rust", risc "rush", āre "propriety, privilege".

Omarishara – OE cwene “woman", đrea "threat".

Sakeni – OE sacian “to argue", sacu "fight".

From Sakeni, the Anglo-Saxons moved into the Inguri River valley, whose name also has Anglo-Saxon origins: OE enge "narrow," wǣr "splashing water." The following toponyms mark the Anglo-Saxons' further movement:

Kvemo and Zemo Marghi – OE mearh “horse". Kvemo from Geo. ქვემო "lower", Zemo from Geo. ზემო "upper". It is interesting that a specialist in the topography of the Caucasus, writing about the road from Teberda to the Tskhenis-tsgali River (the Horse River) [BLARAMBERG JOHANN. 2010].

Gentsvishi – OE a-cwencan “to extinguish, vanish", wīsce "meadow".

Nodashi – OE neod “wish", ǣsce "investigation, claim".

Lezgara – OE leas “free, single", gara "foothills".

Mestia – OE mǣst “most", ea "river".

Lakhiri – OE leah “field, midow, forest", ierre "erring".

Adishi – OE ād "fire", æsc, asce "ash".

Lalkhori – lǣl "welt", "bump", "blue spot", horh "dirt", "mucus".

Ushguli – OE wæsc "washing", gūl "reed".

Aylama – OE eġe (ġ = Gmc j) "fear, terror", lama "sick, weak”.

Anglo-Saxon place names on both slopes of the Main Caucasian Range.

As we can see, some of the place names cited may correspond in meaning to riverine areas. By settling the valleys of the Inguri River and its tributaries, the Anglo-Saxons reached the upper reaches of the Main Caucasus Range and moved further along it, as evidenced by these place names:

Tsana – OE cian "gills".

Tevresho – OE teoru, tierwe "tar, resin".

Glola – OE gleo "joy", la "see!"

Shovi – OE scu(w)a "shadow", "protection".

Oni – OE wana "shortage".

The distribution area of Anglo-Saxon place names in the Chkhalta, upper Kodori, and upper Inguri basins corresponds to the Svan settlement area. The Svan language belongs to the Kartvelian language family, meaning that genetically, Svans are related to Georgians.

At left: Svan towers. Photo from Wikipedia.

Besides place names, other facts can be found about the presence of Anglo-Saxons among the Svans.

These traits must be sought in the cultural characteristics of the inhabitants of the mountainous country of Svaneti. The Svans are distinguished by their high skill in metalworking with non-ferrous metals. It isn't easy to imagine that this skill arose or developed among the mountaineers without external influence. The construction of quality housing and especially watchtowers, unspecified among them, also requires explanation. Travelers and explorers were always amazed and fascinated by the towers rising to the sky, small villages scattered on the mountain slopes, guarded by graceful towers. This appearance of Svaneti gives grounds for various assumptions:

The mobility of this microcosm is demonstrated by a clearly established, constantly functioning communication system, which helped the people of Upper Svaneti establish an uninterrupted connection not only with the people of neighboring Khevi, but also the other regions of the Caucasus. In Ushguli, the border community of Upper Svaneti, one can find all types of architectural heritage, especially secular architecture. Its villages consist of complex residential houses. They served as a common village defensive system against a foreign enemy invasion; at the same time, during internal disagreements and quarrels among the community’s population, which could have led to blood revenge based on local traditions of vendetta, the houses also performed the function of protecting the family. Svans living in “big, extended families” required a unifed system of defense (ELIZBARASHVILI IRENE, GIVIASHVILI IRENE. 2023: 42-43).

Ushguli is notable in many ways. For example, there is a toponymy “Tushre Namzigv” which indicates about the people of Tusheti living here. The legend is interesting but it should be clarified when Tushi people could settle here. There is an opinion that “the location of Ushkuli to the northern border of Georgia where the several crossings gathered makes the opinion completely natural that both “Tamari’s Tsikhe (Fortress) and non-typical Svan towers were built by the central government of Georgia who possibly thought it necessary to put the Tushuri garnison in this fortress [TOPCHISHVILI ROLAND. 2016].

The connection between Svaneti and Tusheti is no coincidence. Tusheti is located adjacent to Khevsureti, home to descendants of the ruling Khazar dynasty of Anglo-Saxon origin (see Khazars – Khevsurs). Thus, it can be concluded that the Anglo-Saxons of Khazaria and Svaneti maintained close ties. This echoes the idea of the existence of two Alanic states, discussed below.

Many Svans have light hair, which distinguishes them from Georgians. They call themselves "schnau," which is reminiscent of the Old English snāw (snow). The Anglo-Saxons must have blended in with the Svans, but some traces of Old English must have survived in the Svan language. Borrowings from Old English can be found primarily in the socio-cultural vocabulary of the Svan language, since the Anglo-Saxons must have been at a higher level of social development. However, it is unlikely that anyone would undertake such a search without knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon presence in Svaneti. Explanations for obscure words from this region are sought in the languages of neighboring and distant neighbors.

Regarding the Svan word for “temi” (community) indicating the family name, was originated from the Greek language long ago, probably by the time when one family had definitely been one community (temi) [Ibid].

However, this Svan word is phonetically and semantically well related to OE team "offspring, tribe, family"

At one time, it was suggested that Alania was divided into East and West Alanya (that is, Alanya proper). A separate dynasty ruled in each of these parts of the country, each with its own original material culture. The author of the idea proposed his delimitation of the early medieval archaeological cultures, which “reflects a very long coexistence in the north of the Caucasus of two main ethnocultural regions – the steppe (included in the region of the steppe cultures of the Northern Black Sea region, the Sea of Azov region and the Volga region) and the mountainous (properly Caucasian) one … ” (KUZNETSOV V.A. 1973: 73).

However, this theory turned out to be unsupported by the evidence. On the contrary, the sources clearly show that Alanya had only one ruling dynasty at any given time, although it is doubtful how much its people identified with the country or dynasty (LATHAM-SPRINKLE JOHN. 2018, 3). The opponent of the theory claims:

… whilst there is evidence for regional diversity in these sources, it cannot be summarised as a distinction between two long-lived, dynastic, territorially bounded polities. (Ibid: 5).

In addition, there is reason to believe that the term *As opposed by V.A. Kuznetsov the Alans, does not contain a sign of ethnicity but is an identifying word for any Central North Caucasian tribe, and it retains this meaning in a number of regional languages. In Abkhazian, for example, all the peoples of the North Caucasus are called Ases. This meaning – or more precisely, the use of the term "As" or "Os" to designate a certain community of the valley – is also found in the languages of the North Caucasus (Ibid: 11-12). Moreover, even the Chuvashes, especially the older ones, still say: “Epir Asem” (we are Ases). Just the Ossetians call the Balkars the Ases too. However, they themselves are called by a similar word the Ases (Avses) by the Georgians. At the same time, there is no single self-name for Ossetians, their widespread name comes from the Georgian, and the self-identification of individual Ossetian sub-ethnos (Digorians, Irons, etc.) do not contain any hints of the ethnonyms of Alans or Ases. Further examining the cases of the use of the word “aces”, Latham-Sprinkle comes to the following conclusion:

If the term *As originally referred to a local community, this may suggest that the primary method of self-identification within the Central North Caucasus remained the local community, rather than ethnicity or kingdom. In any event, it seems that the distinction between the terms *As and Alan was a complex one, which changed considerably over time, and cannot, as Kuznetsov suggested, be explained as a longstanding, binary ethnic or political division (Ibid: 12)

In 1888, on the right bank of the Bolshoy Zelenchuk River, a stone stele with an inscription in Greek letters was found 30 km from the village of Nizhniy Arkhyz (see the figure on the right). The decoding of the inscription was made by V.F. Miller using the Ossetian language. With small corrections, the reading is now accepted in science, and the dating of the stele is determined by 941 year (DHURTUBAYEV M. 2010: 198).

Miller believed that there was a Christian city in this area, from which the ruins of churches were preserved, and suggested that it was the center of the Alan diocese (metropolis), which is mentioned in Byzantine literature. However, not all agreed with the decoding of Miller, because he introduced eight additional letters into the text, which were absent on the stele and without which it can not be by means of the Ossetian language (Ibid).

At right: Drawing of the inscription of Zelenchuk stele in Dhurtubayev'в book taken from V.A. Kuznetsov (Ibid: 199).

The inscription has various reading options, including the use of Ossetian, Kabardian, Karachay-Balkarian, Vainakh, and, possibly, other languages, and disputes about its language continue to this day. The stele itself was not preserved, attempts to find it in 1946 and 1964 did not bring success (KAMBOLOV T.T. 2006: 166). Without the original, one cannot speak about the accuracy of text rendering, and this additionally complicates the decoding of the inscription. The strange thing in this story is that Miller, Abaev, and other experts in Iranian languages did not give decryption of the name Arkhyz itself, which could add them confidence about the Ossetian origin of the stele.

The fact is that in the mountainous region of Arkhiz there are several toponyms which are decrypted precisely with the help of the Ossetian language:

Arkhyz, a river, lt of the Psysh, lt Of the Great Zelenchuk, lt of the Kuban River – Os. ærkh "piece" "splinter", "sliver".

Kardonikskaya, a stanitsa (village inside a Cossack host) in Zelenchuk district of Karachay-Cherkessia – Os. kærdo "rear-tree", nigæ "riverside covered with grass".

Mara, a river, rt of the Kuban' River – ос. mæra "hollow".

Synty, the former name of the aul of Lower Teberda in Karachai-Cherkessia – Os. synt "raven", syntæ "net, snare".

Zagedan, a town and a river, rt of the Bolshaya Laba River in Karachay-Cherkessia – Os. dzag "full", don "water, river".

Such an accumulation of Ossetian place names on a small territory indicates the presence of the Ossetians at some time in Alania, which could be reflected in written sources. Subsequently, the Ossetians could be forced out by the Alans to the places of their modern emplacement, and this entailed confusion in the localization of Ossetia, which Zuckerman notes:

… having only inaccurate translations, Muller made almost surreal conclusions about the location of ethnic groups: he placed the Alans in the west, at the source of the Kuban River, the Ases to the east, then again the Alans – even further east, in the country of Ardoz (ZUCKERMAN C. 2005: 78).

In turn, Zgusta, having no reliable historical evidence and even without a clear idea of the places of Ossetian settlements in the Caucasus, made a hasty conclusion about the Ossetian text on the stele and declared the existence of Ossetian writing already in the Middle Ages. No other data confirming this conclusion has been found so far, however, the authority of L. Zgusta, who saw in the text a relic of the Proto-Ossetian language (ZGUSTA LADISLAV. 1987), contributes to the fact that Abaev’s conclusion still has adherents.

Having my own opinion about the ethnicity of the Alans, I think that the inscription was made in a language close to Old English. I wrote the clearer signs on the stele as follows: νικολαοσ σαχε θεφοιχ ο βολτ γεφοιγτ πακα θαρ πακα θαν φογριτ αν παλ αμ απδ λανε φογρ – λακα νεβερ θεοθελ. I propose the following decoding of the inscription: "Sachs Nikolai is buried here, doomed to death by a traitorous arrow of an insidious servant, decorated with a strong pillar decorating the path – a gift from his nephew Theophilus". Possibly, Sakz, Cumanian khan, the brother of Begubars, was buried here. Judging by the names of the Cumanian khans, in the annals, the common name of the Cumans was understood to mean various peoples who inhabited the North Caucasus and the shore of the Sea of Azov. Among them were the Alans-Angles. The name of the brother of Sakz Begubars can be deciphered with the help of OE. beg “berry” and ūfer “shore” (generally “currant”, cf. Ukrainian porіchki (bank berry “the same”). Other Anglo-Saxons among the Cumanian khans could be Iskal and Kytan.

Accurate evidence of the Alan language is found in the poem "Theogony" by the Byzantine writer John Tzetzes. The two Alan phrases from the poem cited by the author can be translated using Old English, following the context. (For more details, see in Russian Zelenchuk inscription and Once again about the Alanian language).

The territory where the stele was found was part of Khazaria, where the conversion to Judaism took place around 740 (KOESTLER ARTHUR. 2006: 33). However, judging by the names, the uncle and nephew were Christians, which means that not all the Anglo-Saxons, who formed the top of the Khaganate, adopted Judaism. Taking advantage of the fall of Khazaria after the campaign of Prince Svyatoslav in 968, the Christian part of the Anglo-Saxons established their state of Alania. However, even before this, the western province of the Khaganate had its ruler, who was called the exusiocrator in Constantinople. His relations with the central government were complicated:

… the exusiocrator of Alania does not live in peace with the Khazars, but considers the friendship of the basileus of the Romans more preferable, and when the Khazars do not wish to maintain friendship and peace with the basileus, he can greatly harm them, both lying in wait on the roads and attacking those who go unguarded during the crossings to Sarkel, to Klimata and Kherson. Suppose this exusiocrator tries to hinder the Khazars. In that case, both Kherson and Klimata will enjoy a long and deep peace, since the Khazars, fearing the attack of the Alans, find it unsafe to march with an army to Kherson and Klimata and, not having the strength for war against both at the same time, will be forced to keep peace (CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITIUS. 1961: 11).

Thus, it can be concluded that in the originally centralized Khazaria, a split arose due to differences in the religious beliefs of the authorities after the adoption of Judaism by the ruling elite of the Khaganate.

The names of the kings of Alania may indicate that the Anglo-Saxons were the kingdom's ruling elite. Queen Tamara of Georgia (r. 1184-1213) was the granddaughter of the “King of the Alans” Huddan, and his name can be understood as "Person of high dignity" (OE. had/hæd "person", "rank", "dignity",dūn "height", "mountain"). In turn, the queen married David Soslan, supposedly some Alanian prince. The name Soslan can be associated with OE. sūsl "suffering, torment" (-аn – the suffix) and other similar words. Such an interpretation does not correspond to a high origin, but the fact is that nothing is known about the ancestors of Soslan. It is assumed that the royal dignity could be attributed to him for political reasons in later times.(LATHAM-SPRINKLE JOHN. 2018: 20-21).

News of the Alans in the Caucasus came from travelers in the Caucasus until the 18th century. The last evidence of the presence of the Alans north of the Klukhor pass in the amount of “one thousand souls” was the message of Jan Potocki in 1797 (ZUCKERMAN C. 2005: 82).

There are uncertain assumptions about the existence of an English colony in the North-Eastern Black Sea, based on the reports of medieval chronicles about the flight of part of the Anlo-Saxons after the Norman conquest in 1066. Indeed, there is no doubt that the imperial guard, which existed until the siege of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204, also included “English Varangians”. The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Constantinople could be associated with memories of their distant ancestral home in the east. After some time, some of them wanted to establish their own kingdom and asked the emperor (Alexios Komnenos?) to provide them with several cities where they could merge. Allegedly, they were given territory somewhere on the northern coast of the Black Sea (GREEN CAITLIN R. Dr. 2015). At that time, the Byzantines, busy fighting the Turks and problems with the Crusaders, were not interested in these lands and what was happening there was unknown to them. However, the settlements of the Anglo-Saxons in the North were known. One can think that the newcomers could be supposed to go to their compatriots, or the very existence of these settlements gave rise to the legend of New England somewhere in Crimea and on the Caucasian coast. As proof of the legend, several toponyms are given on the Venetian portolan of 1553 and other old maps. It is more clearly spoken about Londia (Londina), the name of which is associated with London, and there are no other toponyms on the portolan. On it, all the names are not local, but Italian and there is no trace of any Chechen or Kurdish ones, although they should have already existed (see Pechenegs and Magyars, Cimmerians in Eastern European History). This raises doubts about the use of the names of the indicated maps by the population. The name of Londia was supposed to be a derivative of it. lontano “far away”. It really was far from the main Genoese port of Kaffa in Crimea. Thus, without denying the existence of New England, we must add some clarification to the legend.

Restoring the prehistory of the Anglo-Saxons in a wide area of Eastern Europe, it should be noted that most of them were not directly related to the Alans. While the Alans, who settled on the Northern Black Sea coast and remained there until the arrival of the Huns, the Angles and Saxons the Angles and Saxons moved their way towards Germany, and from there they already reached the British Isles. The study of Anglo-Saxon place names in Central and Eastern Europe helps to restore the picture. As in the case with the mass migration of peoples, part of migrants remains always at the place of temporary residence. The rest of the tribesmen set out again after some time (a year or two or more). So a chain of settlements, whose names often survived to our time, arises along the way. In our case, we have two such chains of Anglo-Saxon place names, one which crossed central Poland, and the second goes along the Carpathian Mountains and through the Moravian Gate to Bohemia. Obviously, the Angles moved through central Poland and then through northern Germany. The Saxons came in Bohemia and through the valley of the Elbe River entered Germany where the states of Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt is now. Here, most of them stayed permanently. The other part has moved on to the North Sea coast where is now the state of Lower Saxony.