Circassians

During the study of prehistoric processes in Eastern Europe, an assumption was made about the ethnic identity of the Pechenegs and Chechens. The starting point for testing this assumption was data on the close historical relationship between the Pechenegs and the Magyars, as a result of which an outline was written Pechenegs and Magyars. The Pechenegs played a significant role in historical events in Eastern Europe, but other peoples of the North Caucasus also had to take some part in them. After all, the chronicles contain information about the Kumans or the so-called “black hoods” (Uzes, Torks, Berendeys, Kovuis, Kaepichis, Turpeis), among whom there could have been Caucasian people. Konstantin Porphyrogenitus reported about some Kavars, also called Kabars. He pointed out that the Kavars “come from the Khazars,” which may not indicate their origin, but their place of primary residence. Then they can be associated with modern Kabardians and further with other peoples of the Abkhaz-Adyghe language group. Closer family relations distinguish a group of peoples collectively called Adyghes:

The self-name of the tribes of the North-Western Caucasus, related in language and culture, sounds like “Adyghe”; today the Adyghe people are considered to be Adygheans, Kabardians, and Circassians (GANICH ANASTASIA. 2005: 35).

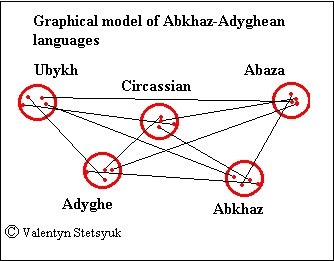

The related relationships of the Abkhaz-Adyghe have already been studied using graphoanalytic method. This group includes Abkhazian, Abaza, Adyghean, Kabardino-Circassian, and dead Ubykh, about which, however, documented evidence remains. At the same time, Kabardino-Circassian and Adyghe are so close that we can assume their joint origin from the same parent language. We can talk less confidently about the common proto-language of Abkhaz and Abaza. However, to construct a graphical model (scheme) of kinship, the data of Sergei Starostin, presented for all of the above five Abkhaz-Adyghe languages in the project The Tower of Babel), were accepted.

In accordance with these data, the relationship model of these languages is constructed very easily, it is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 The graphical model of the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages.

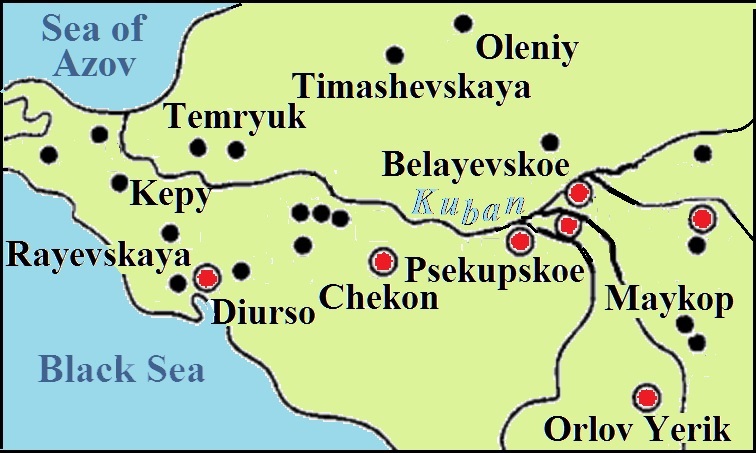

A presumable place on the map for the obtained model should be looked for somewhere near the modern settlements of the Abkhaz-Adyghe peoples, but a small number of languages of this group do not allow for precise localization of their prehistoric ancestral home. In addition, there is no place for an area of the Kabardino-Circassian language in the place of their proposed location. Obviously, Kabardino-Circassian, and Adyghean, in fact, had a common individual genetic ancestor. Under this assumption, the model can be correlated with the territory of the Western Caucasus, where four fairly distinct geographical areas can be identified on the Black Sea coast (see the map in Figure 2). In this case, the ancestors of the Adygeans, Kabardians, and Circassians, whom we give the conventional name of the Adyge, should live in the area between the rivers Mzymta and Bzyb, and the ancestors of the Ubykhs populated area between the rivers Mzymta and Shahe.

This localization of the model allows us to state that the Abkhazians stayed at the places of their primary settlement between the Bzyb and Kialasur rivers, somewhat widening by now their original territory for the Bzyb and Kodori rivers.

Fig. 2 The map of areas of the formation of the Abkhazo-Adyghean languages on the West Caucasus.

The presence of an area between the Kelasur and Kodori rivers corresponding to the kinship model, suggests that the Abazin language developed exactly there, in the neighborhood of the Abkhazian area, and this caused special proximity of these languages.

The formation of individual Proto-Abkhaz-Adyghe languages occurred during the conversation from the Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age (SAVENKO S.N. 2011: 61). We can say that this happened before the Turkic tribes from their ancestral home in the steppes of Ukraine in the 3rd millennium BC. advanced to the North Caucasus. Later, Adyghe tribes began to arrive here through the Belorechensky crossing and, since the steppes were already occupied by the Turks, they populated the northern slopes of the Main Caucasus Range. By that time, the Turks had already domesticated the horse and from them, the Adyghe borrowed the basics of horse breeding and had in time great success in this area of animal husbandry. This is evidenced by the famous Kabardian breed of riding horses. An idea of the level of culture and the peculiarities of life of the Adyghe of that time can be obtained after an in-depth study of the Novosvobodnaya culture, which existed in the western Caucasus until 2900-2880 BC. The more studied dolmen culture followed it. It was widespread on both sides of the Main Caucasian ridge, and its bearers were mainly engaged in animal husbandry since the lack of appropriate land hampered the development of agriculture. At the end of the second millennium, the Adyghe were part of the cultural and historical commonality of the Maykop culture and were the creators of its Western local version (see the map in Fig. 3). The main difference from the eastern variants of the Maikop and later Koban cultures should have been more developed horse breeding, since in the Central Caucasus back in the second half of the first century BC horse breeding was of an auxiliary nature (PROKHORENKO Yu.A. 2014, 25).

Fig.3 Area of monuments of Maikop culture. Psekupsky option

According to (REZEPKIN ALEKSEY. 2020: 516).

Burials are marked in black, and settlements in red

On the contrary, by the beginning of the 1st millennium BC the Adyghe already had good cavalry. Preliminary studies have shown that the Adyghe were part of the Cimmerians who inhabited the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region and the other part were the ancestors of modern Kurds (see Cimmerians in Eastern European History). Their role in the history of Eastern Europe is well-known to specialists:

The Cimmerians were among the most prominent representatives of the early nomads. They are associated with the spread of nomadic cattle breeding, iron products, as well as the first cavalry. The use of horses for riding, and the appearance of the first horsemen in the Black Sea steppes at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC led to a revolution in communications, facilitating connections between distant regions. (MAKHORTYKH SERGEY VLADIMIROVICH. 2008: 4)

The spread of horse riding in the Cimmerian era meant that well-trained cavalry units could move quickly and defeat the enemy over vast distances. The appearance of cavalry changed military affairs in most regions of South-Eastern Europe. Thanks to the Cimmerians, new horse equipment and weapons were spreading across the Eastern European steppes, suggesting a higher level of specialization in military tactics and equipment than before, which, in turn, was combined with a higher level of horse breeding and management (ibid: 382).

Thanks to good cavalry the Adyghe were able to undertake long-distance military raids. The priority direction of such campaigns was the countries of Western Asia. Convenient crossings in the mountains of the Western Caucasus made it easier to carry out such enterprises.

In the 8th century BC, The Adyghe were already such a great force that they could join in the confrontation between individual countries in Transcaucasia and left their name in history just as the Cimmerians. Usually, the Cimmerians are considered an Iranian-speaking people and the historically attested names of their kings are considered Iranian, but these names do not have a reliable interpretation in any of the languages (KHRAPUNOV IGOR'. 2012: 9). Meanwhile, the Kabardian language provides such an opportunity:

Teushpa, a Cimmerian king, who in 679 BC lost the battle against the Assyrians, during which he was killed. Similar name Τεισπισ (Teispis) was had the son of Achaemen, the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty in Persia (YELNITDKIY L.A. 1977: 27). This is a strong argument in favor of the Iranian identity of the Cimmerians, but in the Persian language the name has no explanation. On the contrary, a good opportunity for this is provided by Kabardian – Kab. teuščăbăn “to crush” is suitable for the name of a warlike king, especially when the name of another king, Ligdamis, is also well deciphered using Kabardian (see below).

Lygdamis, a Cimmerian king, of the same time and his name has nothing similar in Iranian languages – Kab. l'yγыгъă “courage” and damă “wing, wings”. He was Teushpa's successor and made attacks on Phrygia, Lydia, and Cilicia and also died in battle:

… Akkadian sources allow us to establish that in 644 B.C., the Cimmerians’ most successful raid was on Lydia, in which King Gig was killed. Apparently, this raid affected not only Lydia, but also Ionia, and that is what Greek sources meant when they reported the same raid by the Cimmerians. The same Akkadian sources describe the death of Ligdamis/Dugdamme dating it to 641 BC, i.e., three years later (IVANCHIK A.I. 2005: 123).

Somewhat earlier than the Cimmerians, the Kurds began their travels across Asia Minor, arriving from the Balkans and gradually moving to the east, where they met the Adyghe. Obviously, good relations were established between them, because the local population called both of them with the same word

Thus, if you completely rely on the subjective testimony of contemporaries and the legends they left behind, it is impossible to restore the history of the Circassians, meanwhile, those who are interested in it mainly rely on them:

Interest in the rich history of the Circassians, in their vibrant and original way of life was supported for a long time by the news of Eastern and European chroniclers and travelers (BUBENOK O.B. 2019: 3).

The first results of ethnogenetic research were so often confirmed in historical anthroponymy and toponymy that onomastics became another effective research method, especially in cases where either historical documents were lacking or they were contradictory. Working with a dictionary of the Kabardian language in attempts to restore the history of the Circassians gave reason to look for traces of the presence of the Cimmerians-Adyghes in the Greek language. First of all, attention was paid to Greek words beginning with the letter psi (ψ). There is no corresponding sound in the Proto-Indo-European language from which Greek is derived, and it is difficult to find an Indo-European etymology for all words beginning with ψ. Such attempts are hypothetical in nature, but when searching for plausible etymologies, the languages of the Abkhaz-Adyghe group, in which the sound combination ps is widespread, were not involved. Below are several Kabardian words that have matches in Greek:

Kab. psal'ă 1. "word", 2. "language", 3. "conversation", 4. "rumor" and its derivatives: psăl`ăn "to speak", psal`ămaq "conversation", "talk" and many others with a narrower meaning – Gr. ψελλός "speaking inarticulate, poorly" according to Frisk "onomatopoeic" (FRISK H. 1960-1972, volume two: 1132) , ψαλμος "psalm", which is related with Gr ψάλλω "string" (of a musical instrument), without a specific etymology (ibid: 1129). Surprisingly, for some reason, this common word is not considered in the Etymological Dictionary of Adyghe (Circassian) Languages, although there is an article bze “language” (SHAGIROV A.K. 1977). The obvious common origin of these words remains unnoticed.

Kab. psă "soul", psău "alive, living" psău "to live" – Gr. ψῡχή "breath, life, soul." Having examined several derivatives of this word, Frisk concludes: “The further history of ψῡχή lies in prehistoric darkness” (FRISK H. 1960-1972, volume two: 1141-1142).

Kab. psă "soul" and ud "witch, sorceress" – Gr. ψεύδομαι, "to lie, fib". Frisk doesn’t give anything phonetically and semantically close, except for Armenian sut (FRISK H. 1960-1972: 1132-113), which only emphasizes the dark origins of the word. The comparison of Adyghe and Greek words has already been noted in the literature, but it is considered arbitrary (SHAGIROV A.K. 1977. volume two: 14)

Kab. psy "water" – these words may be associated with this root: Gr. ψακάς "drop", ψίζομαι " to weep", ψύδραξ "blister, bleb" (Kab. psybyb "blister, bleb"), Gr. ψεδνός "thin" (Kab. psyγuă "thin").

These borrowings into the Greek language from the Cimmerians indicate that they were not inferior to the Greeks in cultural development, and confrontations with the peoples of Asia Minor enriched their political experience. At that time, the lingua franca in Asia Minor was the Akkadian language, related to Arabic, and the Cimmirians borrowed from it some words, the origin of which linguists attribute to Arabic borrowings. They are still preserved in the Kurdish language and should be in the Circassian languages. These include Kab. uălij “ruler”, as evidenced by the deciphering of some Circassian toponyms (Velizh, Nevel).

After unsuccessful adventures in Asia Minor, the Cimmerians were forced to leave it. It is believed that after the defeat of Lydia in the war with Media and Neo-Babylonia, the Cimmerians and Scythians who supported Lydia, under the terms of the peace, “had to go back to where they came from, i.e. to the Northern Black Sea region" (ARTAMONOV M.I. 1974: 34). The Adygs returned to the places of their former settlements, and the Kurds, moving along the eastern shore of the Black Sea, reached the Taman Peninsula and settled the nearest free area along the banks of the Kuban, as evidenced by the toponymy that has survived to the present day. Using their Asia Minor experience there, they began building their own state, which over time received the name Bosporus Kingdom. Having gained influence in the Northern Black Sea region, they soon became the largest ethnic group in this region. The Adygs also increased their numbers and, according to estimates, according to Sarmatian Onomasticon they accounted for 10% of the population of all Sarmatia. Below are names of Adyghe origin from a total of 348 words of a representative sample of onomasticon. The Kabardian language was used to decipher the epigraphic material. The Latin transcription of Kabardian words was done according to the rules adopted by the Tbilisi school of Caucasian scholars (SHAGIROV A.K. 1977. volume one: 39)

Αβλωνακος (ablo:nakos), the son of Arseouakhos (see Αρσηουαχος), the strategos in Olbia. Latyshev – Kab. 'ăblă "arm", unaγă "household".

Αβροαγος (abroagos), the son of Susulonos (see Σουσουλον), the strategos in Olbia; Αβραγοσ, the son of Sambut (see Σαμβουτοσ), the father of Kharaxenos (see Χαραξηνοσ), the son of Khuarsadzos (see Χυαρσαζοσ), Latyshev – Kab. abraγuă „great”.

Αργουαναγος (arγouanaγos), the son of Karakht, the father of Karakht, Kenozart (see Καινοξαρθοσ) and Nawtim, the princeps in Olbia, Latyshev – Kab. eru "angry, cruel", γwynăγw "neighbour". It was not possible to decrypt all the names in one language.

Αρσηουαχος (arse:ouakhos), Αρσηοχος (arse:okhos), Αρσηοαχος (arse:oakhos), a princeps in Olbia – Kab. hărš "gathering place in the afterlife", euvexyn "to descend".

Αυχαταιι, Scythian race, descendants of Lipoxais – Kab. euxyn "to beat, hit", taj "leyer".

Αψαχος (apsakhos), Tanais, Knipovich; Αψωγασ (apso:gas), Olbia, Latyshev – may be connected with Os. æfsæ „mare” or with Kab. epsyxyn "to get off the horse" ("infantryman").

Bevka, a Sarmatian king – Kab. băvyγă "wealth, abundance".

Βωροψαζος (wo:ropsadzos), the son of Kardzey (see Καρζεισ), Olbia, Latyshev – Kab. wăr "stormy", psă "soul", ƺă "army".

Δαππασις (dappasis), Hermonassa, Latyshev – Kab. dăp “heat, coals”, pasă “early”.

Zacatae, a tribe in Asiatic Sarmatia, the territories between the Don and the Volga rivers, Pliny – Kab. zăquăt "standing close together, united".

Zuardani, a tribe i Asiatic Sarmatia, Pliny – Kab. zăuerej "warlike", dăn "agree".

Ιαζαδαγος, Ιεζδαγοσ (iadzadagos, iedzdagos), Olbia, Vasmer – Kab. i'ă, interjection encouraging action, zădăkuăn "go together".

Ιναρμαζος (inarmadzos), the son of Kukodon (see Κουκοδων), Olbia, Knipovich, Levi – Kab. in "great", armuuž' "laggard".

Ινσαζαγος (insadzagos), the son of Sthadzeis (see Σθαζεισ), Olbia, Latyshev – Kab. in "great", seƺe "blade of knife".

Καδανακος (kadanakos), the son of Nawag (see Ναυαγοσ), Tanais, Latyshev – Kab. k`ă "finish", dănaγ "boundary".

Καρζεις (kardzeis), the son of Boropsadz (see Βωροψαζοσ) – Kabard. k`arc "acacia, robinia".

Κασακος (kasakos), the son of Kartsey (see Καρζεισ), the strategos in Olbia, Κασαγοσ (kasaγos), the father of Arsewakh and Kasken, Olbia, Latyshev – Kab. k'asă 1. "late" 2. "the youngest in the family"; -g

, a noun suffix from an adjective.Κασκηνος (kaske:nos), the son of Kasag (see Κασακοσ) – Kab. qăsk'ăn "shudder".

Καφαναγος (kaphanagos), the father of Mourdag) (see Μουρδαγοσ), Olbia, Latyshev – Kab. qăfăn “to dance”, -γă, noun suffix from verbal stems.

Κουκοδων (koukodo:n), the father of Inarmaz (see Ιναρμαζοσ), Olbia, Knipovich, Levi – Kab. qăuk'a "killed", udyn "strike".

Κουκοναγος (koukonagos), the son of Rekhovnag (see Ρηχουναγοσ), a market administrator in Olbia – Kab. qăuk'a "killed", năgu "face".

Μαης (mae:s), the son of Mae. Kerch. CBI – Kab. mae "nutritious, very fatty".

Μαισης (maise:s), Gorgippia – Kab. maisă “sharp saber, sharp knife”.

Μευακοσ (meuakos), the father of Navak (Ναυακοσ), Tanais – Kab. myvă "stone", qaz "goose".

Μουρδαγος (mourdagos), the son of Kafanag (see Καφαναγοσ), Olbia, Latyshev – Kabard. mamyr "silence", dăgu "deaf".

Ναυαγος (navagos), the father of Kadanak (see Καδανακοσ), Tanais, Latyshev – Kab. nă "yey", vaγuă "star" .

Νιχεκος (nikhekos), Gorgippia – Os. nix „forehead”, Kab. năxejk'ă “in spite of”.

Ουαμψαλαγος (ouampsalagos), Olbia, Knipovich – Kab. auan "mockery", psaleγu „interlocutor”).

Ουαρδανης (ovardane:s), the name of the Kuban River by Ptolemy is not a “wide river”, as Abaev suggests (Os. urux „wide” and don „water, river”), but rather a “stormy river” (Kab. uăr „stormy”). The Kuban flows through the former Adyghe territory (the ancestors of modern Adyghe, Circassians, and Kabardins), but for same time, Ossetians dwelled here too.

Ουαχωζακος (ouakho:dzakos), Olbia; Οχωδιακοσ, the son of Dula (see Dula), the father of Azas and Stormais (see Στορμαισ), Tanais, Latyshev – Kab. eγăǯak'uă „teacher”. Liya Akhedzhakova, the actress, Adyghe by nationality.

Ουμβηουαρος (ombe:ouaros), the son of Urgbaz (see Ουργβαζοσ), Olbia – Kab. 'ump`ej "naughty, inanimate", uăr „boisterous”.

Ουργβαζος (ourgbadzos), the father of Umbevar (see Ουμβηουαροσ), Olbia – Kab. uărq "nobleman", baƺă "fly".

Ουργοι (ourgoi), according to Strabo one of the Sarmatian tribes – Kab. uărq "nobleman". Cf. Ουργβαζοσ.

Ρηχουναγος (re:khounagos), the father of Kukunag (see Κουκοναγοσ), Latyshev – Kab. erăxu "well", năgu "face".

Σθαζεις (sthadzeis), the son of Insadz (see Ινσαζαγοσ) – Kab. ščăǯaščă "giant, knight".

Χοζανια (khodzania), female name, Panticapaeum, Latyshev – Kab. xuăǯyn "spin".

Χοαροσαζος (khoarsadzos), the father of Abrag (see Αβροαγος), Tanais, Χουαρσαζος, Olbia – Kab. xuăr "parable" săƺă "blade of knife".

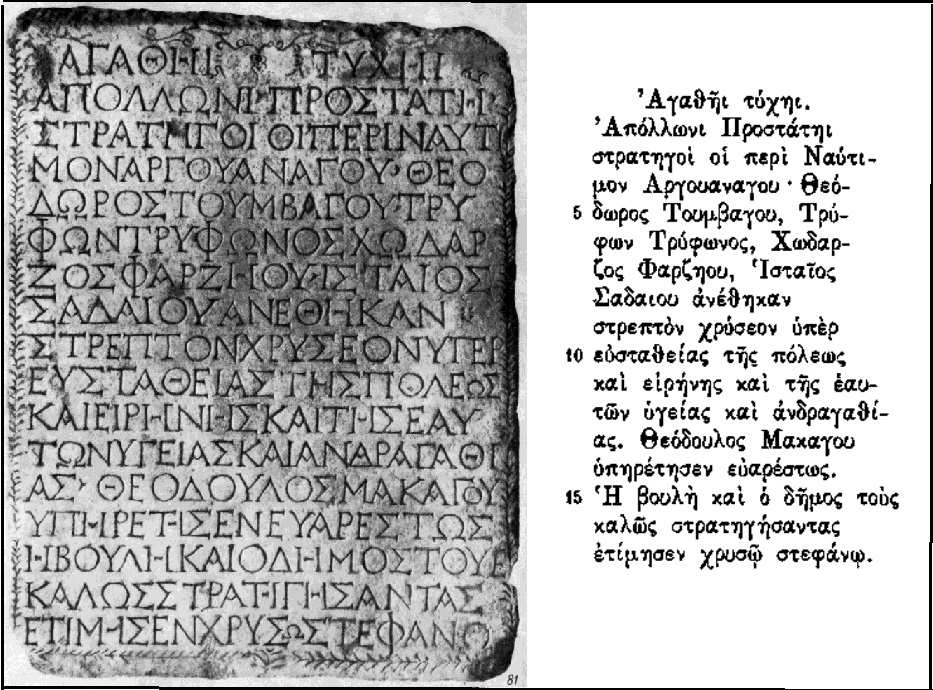

Fig.4 Marble slab from Olbia and its text

Second half of the 2nd century BC. Size: 380x300 mm.

(KNIPOVICH T.N., LEVI E.I. 1968, Table XL )

Translation of text on the slab: To good time! Strategists with Nautim, the son of Arguanag, led by Apollon Prostat, Theodor, son of Tumbag, Tryphon, son of Tryphon, Godarz, son of Farsei, Gistei, son of Saday, dedicated a gold necklace for the welfare of the city, for peace and for their own health and courage. Feodul, the son of Makag, served excellently. The Council and the people honored the strategists with a golden crown for the excellent performance of the post.

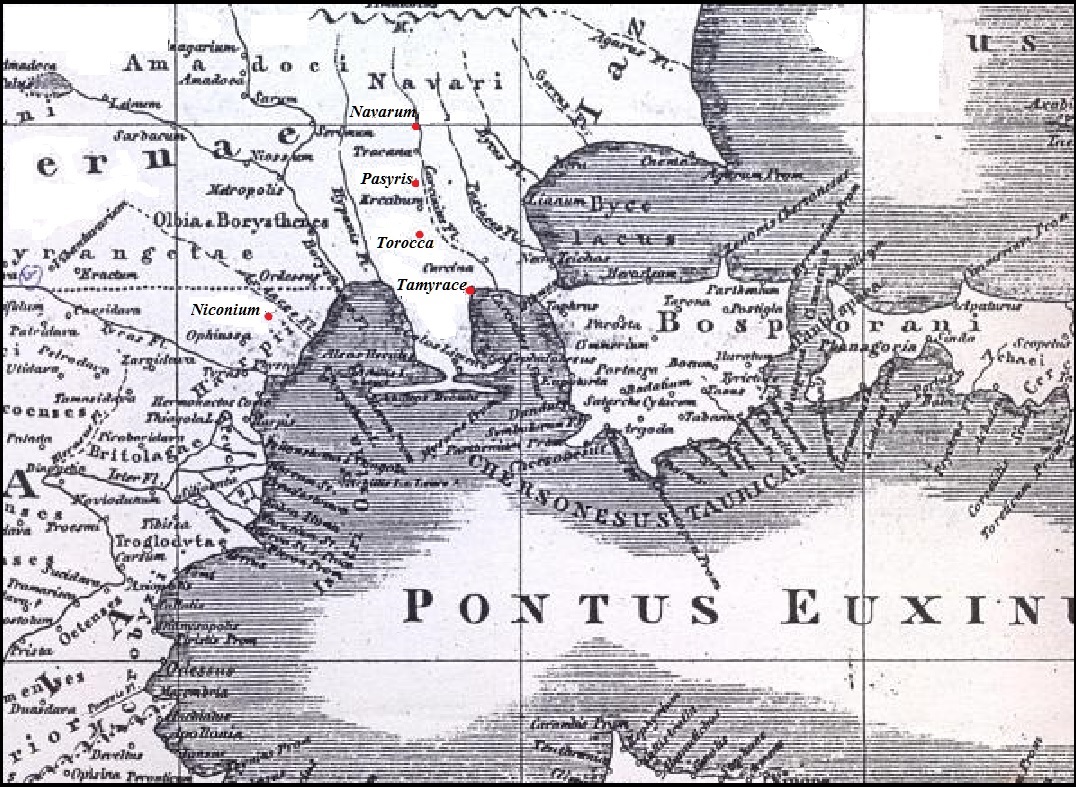

According to the onomasticon, most bearers of Adyghe names dwelled in Olbia. On the site of this Greek colony is now the village of Parutino, the name of which can be associated with the Kab. păryt “leading, advanced”. Since the Kabardian language was used to decipher onomastics, Olbia should have been populated by Circassians. It should be recalled here that modern Circassians and Kabardians speak practically the same language, while the Adyghe language, being very close to them, is still noticeably different. Using further for convenience the name Circassians, we will have in mind the common ancestors of the Circassians and Kabardians. Thus, there is nothing strange that the names of their settlements in the Olbvia region can also be deciphered using the Kabardian language without making big mistakes. Specialists involved in the toponymy of Scytho-Sarmatia are certainly familiar with the map of the ancient Greek scientist Claudius Ptolemy, published around 150 AD (see the map in Fig. 5). It shows several settlements of the Northern Black Sea region, among which there are several that may be Circassian. The map gives a distorted image of the geography of the Black Sea basin; the location of settlements is very approximate, but their names are real. Here is their interpretation:

Navarum – Kab. nа'uă "visible, clear", --r – the morphological indicator of the nominative case. The name has not survived to this day, but it may have changed and taken the form of Novogradivka, a village in the Kirovohrad Region. Very close to Novogradivka the village of Ketrisanivka is located, which name is also deciphered using the Kabardian language.

Niconium – Kab. nykuăn "to be half filled". On Ptolemy's map, this city is located approximately north of Odessa. In this place, only the name of the village of Mikolaivka can correspond to it. The name change could have occurred under the influence of the name Mykola (Nikola). This assumption is confirmed by the fact that the village of Chigirin is located nearby, the name of which is deciphered using the Kabardian language.

Pasyris – Kab. pasărey "old, ancient". On Ptolemy’s map, this settlement is located south of Navarum. No similar name was found in this place. However, it could retain its original meaning, and then the village of Starogorozhene in the Bashtansky district of the Mykolaiv region on the Ingul River can be associated with this settlement. From the Ukrainian language, its name can be translated as “an old fenced settlement.” The village is indeed located south of Nogradadyvka, which we associate with Navarum. Then the Ukrainians who settled it later must have known the meaning of its name, that is, they learned to understand the Circassian language.

Tamyrace, – Adyghe temyr "north", Kab. k`ă1. "tail", 2. "end". There are no assumptions about the location of this and the next settlement. They were supposed to be located in the coastal zone, where very few ancient settlements remained.

Torocca – Kab. t'orysă "worn", k'ă1. "tail", 2. "end".

Fig.5 The map of Ptolemy

On the map, Circassian settlements are marked in red

As indicated, the previously mentioned name of the village of Ketrisanivka is of Circassian origin – Kab. kytriş'en "to accumulate". The village is located on the Hromokla River, a tributary of the Ingul River. Previously, the name could have had the form Gromoklya in accordance with the peculiarities of the phonology of the Ukrainian language and it can also be associated with Kab. ǧrym "moan" and uk`a "killed". The letter ǧ denotes the voiced labialized sound of the Kabardian language which is denoted usually gu. The name of the Inhul River also can have a Circassian origin – Kab. in "big", gulă "cart, luggage". Why the river might have been named this way remains unclear. One can give examples of several other place names in Ukraine of possible Circassian origin:

Chuhuiv, a city in the Kharkiv Region and the village of Chuhuyeve in the Dnipropetrovsk Region – Kab. ščygu "plato".

The mentioned above the village of Chyhiryn and the city of the same name in Cherkasy Region – Kab. čy "rod" xyrină "cradle".

Daleshove, a village in Horodenka district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region – Kab. dălăž’ăn "to work together".

Fashchivka, a village in Ternopil district of Ternopil Region, two urban-type settlements in Luhansk Region – Kab. 1. f'ăšč "severeness". 2. f`ăšča "name". 3. f`ăšč`a "atteched". This is the most common Circassian place name, it has been found seven times. There are two more settlements in Belarus and Russia, but it is impossible to understand the motivation for the name from the available possibilities. However, it is undoubtedly Circassian.

Lapshyn, a village in Ternopil district of Ternopil Region – Kab. lapščă "shin".

Lypchanivka, a village in the Izyum district of Kharkiv Region – Kab. lepshch "god of blacksmithing".

Lypchany, a village in the Mohyliv-Podilskyi district of Vinnytsia Region – Kab. lepshch "god of blacksmithing".

Murafa, a river lt of the Diester, village in the Krasnyi Kut district of Kharkiv Region – Kab. morafă "beige, light-brown".

Navaria, a village in the Pustomyty urban community of Lviv Region – see Navarum.

Shalyhyne, an urban-type settlement in Shostka district, Sumy Region – Kab. shylegu "turtle".

Shchyrets, an urban-type settlement in the Lviv district of Lviv Region – Kab. shchyr out of shchy "three".

Stara Ushytsia, an urban-type settlement in Kamianets-Podilskyi district, Khmelnytskyi Region – Kab. ušč'a "gaping".

This is not a complete list of Circassian place names in Ukraine; the search for them is being continued and they are all placed on Google My Maps (see Fig. 6). Toponymy provides convincing evidence of the presence of Circassians in Ukraine before the arrival of the Slavs, but some place names indicate cultural contacts between Circassians and Ukrainians. However, anthroponymy speaks even more about this. Despite the fact that over time the Circassians were assimilated by the Ukrainians, their ancestors retained their family names for a long time and, thanks to mixed marriages, many of them became Ukrainian surnames. Below is a list of them.

Badz', 83 carriers of this name, most of all in Zhovkva district of Lviv Region (54) – Kab. baƺă "fly" or băǯ "spider".

Badziuk, 165 carriers of this name, most of all in the city of Kyiv (45) and in Ratniv district of Volyn Region (34) – Kab. baƺă "fly".

Badziukh, 232 carriers of this name, most of all in the Vasylkiv district of Kyiv Region (87) – Kab. baƺă "fly".

Bzenko, 232 carriers, most of all in the Korsun-Shevchenkivskyi district of Cherjasy Region (87) – Kab. bză 1. "tongue", 2. "language".

Bylym, 331 carriers, most of all in the Kozelts district of Chernihiv Region (41) and in Mashivka district of Poltava Region (34) – Kab. bylym "livestock, wealth".

Blashchuk, 1822 carriers, most of all in Kyiv (73), Bar district of Vinnytsia Region (64), Iziaslav district of KJmelnytskyi Region (62) – Kab. blaγă "relative, kinsman".In the Ukrainian language, there is a word blago “goodness, benefit, happiness”, but in terms of meaning the Kabardian word is more suitable for the name.

Hyzha, 180 carriers, most of all in Kyiv (29) and Koziatyn district of Vinnytsia Region (28). – Kab. xyž'ă "brave".

Hupsa, 26 carriers, most of all in the city of Kharkiv (12) – Kab. gupsă "middle, center".

Dey, 257 carriers, most of all in the city of Dnipro (43) – Kab. dey "walnut tree, hazel".

Dzhydzhora, 150 carriers, most of all in Monastyrysko district of Ternopil Region (44) – Kab.

ǯyǯă "shining".

Dzyha (Dzyga ?), 249 carriers, most of all in Kobelaky district of Poltava Region (44) – Kab.

ƺyγă "mouse". The word may originate from Ukr. dzyga, which does not have a generally accepted etymology, can be imitated (MELNYCHUK O.S. 1985: 52).

Dzhyhun, 258 carriers, most of all in Chemerivtsi district of Khmelnytsyi Region (43) – Kab. ǯăгу "play, dance", ǯăгуn "participate in dances, parties". The origin of the Ukrainian dzhigun "dandy" is considered unclear, but a comparison with the Kabardian word is not excluded (MELNYCHUK O.S. 1985: 58).

Dydzhyk, Didzhyk, 14 carriers, most of all in Novyi Buh district of Mykolaiv Region (43) – Kab. dyǯ "bitter", dyǯa "bitterness", "anger".

Kotsaba, 565 carriers, most of all in Kolomyia district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region (86) – Kab. kucabă "striped".

Kulay, 602 carriers, most of all in Volodymyrets district of Rivne Region (68) – Kab. qulaj "rich man".

Kurmak, 48 carriers, most of all in Mykhailivka district of Zaporizhzhia Region (17) – Kab. qwrmaqej "throat".

Mamyrin, Mamyrina 24 carriers, most of all in Snihurivka district of Mykolayiv Region (11) – Kab. mamyr "peace, quiet", "silence".

Mamyrkin, Mamyrkina 40 carriers, most of all in Makiyivka and Luhansk (7 each) – Kab. mamyr "peace, quiet", "silence".

Momryk, 107 carriers, most of all in Yavoriv district of Lviv Region (59) – Kab. mamyr "peace, quiet", "silence".

Momrenko, 29 carriers, most of all in Rozdilna district of Odesa Region обл. (4) – Kab. mamyr "peace, quiet", "silence".

Momro, 27 most of all in Kaniv distroct of Cherkasy Region (7) – Kab. mamyr "peace, quiet", "silence".

Murafa, 109 carriers, most of all in Halych district of Ivan-Frankivsk Region (52) – morafă "beige, light-brown".

Sabala, 35 carriers, most of all in Borshchiv district of Ternopil Region (68) – Kab. sabala "dusty".

Sabiy, 81 carriers, most of all in Simferopol district Crimea (68) – Kab. sabij "vhild".

Tsybak, 205 carriers, most of all in Botshchiv district of Ternopil Region (52) – Kab. cybă "hairy".

Tsoba, 65 carriers, most of all in Zolochiv district of Lviv Region (17) – Kab. c'ob "ox, nowt". Interestingly, the Ukrainian word tsob/sob means a command for the oxen to turn left.

Tsobenko, 224 carriers, most of all in Balta district of Odessa Region (79) – Kab. c'ob "ox, nowt".

Shubak, 96 carriers, most of all in Staryi Sambir of Lviv Region (52) – Kab. šubaq "turtle".

Vaka, 153 carriers, most of all in Zolotonosha district of Cherkasy Region (36) and Znamyanka district of Kirovohrad Region (26) – Kab. vak'uă "plowman".

Zhyhadlo, 926 carriers, most of all in Kyiv (88) – Kab. žygdelă "maple".

Zhyhaylo, 888 carriers, most of all in Zhovkva district of Lviv Region (106), Lanivtsi district of Ternopil Region (66) – Kab. žygej "oak", žygeilă "oakery".

Zhyhun, 774 carriers, most of all in Kyiv (145) and Nosiv district of Chernihiv Region (143) – see Dzhyhun.

Zhyhunov, Zhyhunova, 462 carriers, most of all in Kyiv (34) – see Dzhyhun.

Zhumatiy, 146 carriers, most of all in Dobrovelychkivka district of Kirovohrad Region (22) and Pervomaysk district of Mykolaiv (22) – Kab. žumart "lavish, bounteous".

Fig.6 Circassian onomastics in Eastern Europe

Purple signs indicate place names decrypted using the Circassian language or having other traces of the Circassians. Red dots indicate the settlements in which surnames of Circassian origin are found.

As we see, onomastics convincingly testifies to the presence of Circassians on the territory of Ukraine. In this regard, Ukrainians are interested in getting to know these people. Unfortunately, in Ukraine, the languages and culture of the Caucasian peoples are not studied at university universities, but due to historical circumstances, these topics cannot be ignored, and in Russian literature, you can find a lot of interesting things about the Circassians and other Caucasian peoples in the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy. At the same time, their relationship with the Russians is presented from different positions. Pushkin praised Russia's imperial policy in the Caucasus:

To the indignant Caucasus

Our double-headed eagle has risen;

When on the gray Terek

For the first time the thunder of battle struck

And the roar of Russian drums,

And in the battle, with an insolent brow,

The ardent Tsitsianov appeared;

I will sing your praises, hero,

O Kotlyarevsky, the scourge of the Caucasus!

Wherever you rushed like a thunderstorm – —

Your move is like a black infection,

You killed and destroyed tribes.

…

Drop its snowy head,

Humble yourself, Caucasus: Ermolov is coming!

However, in general, the attitude towards the Caucasian peoples in the intellectual community of Russia is distinguished by objectivity and their characteristics include the following words:

The fact that the mountaineers were distinguished by excellent military skills, instilled in childhood, was noted by historians and ethnographers, officers – participants in the Caucasian War. Thus, historian, the eyewitness of events in the Caucasus N.F. Dubrovin wrote that the most valuable thing for a highlander was the glory of a dashing daredevil who made many daring forays into the enemy’s camp and returned with rich booty (GANICH A.A. 2007: 50).

Recently, there has been noticeable interest in the connections of the Circassians with Ukraine; it can be seen in the book cited above (BUBENOK O.B. 2019). Obviously, this is not accidental, and Circassian-Ukrainian ties should become the subject of scientific research as an integral part of Ukrainian history. In particular, it may be useful to study the influence of the Circassians on the formation of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, the original center of which was located not far from ancient Olbia. In fact, there are no social prerequisites for the emergence of the Cossack military class in the history of Ukraine, and the word Cossack itself has no roots in the Ukrainian language. The supposed borrowing of it from the Turkic languages (MELNYCHUK O.S. 1985: 496; VASMER MAX. 1967: 158) does not have reliable confirmation, because, in the Etymological Dictionary of Turkic Languages, it is generally not considered (SEVIRTYAN E.V. 1974 – 2003), i.e. its presence in them must also be explained by borrowing. It can be assumed that the Turks borrowed the word Kazak and similar from the Circassians – Kabardian k'asă 1. “late” 2. “youngest in the family”, -γ is a suffix that forms nouns from the stems of adjectives. From the formed word came the chronicle name of the Circassians kasoges and all kinds of independent, free adventurers and vagabonds called Cossacks and Kazaks in many languages. This transformation of meaning may seem strange and therefore requires an acceptable explanation. To do this, you should pay attention to the position of the youngest son in the family, which took place in the recent past, but in earlier times manifested itself more clearly:

Even more than one son per father creates tensions – and that within the family, which is not just dealing with two boys, but with the firstborn and his brother. The jealousy or even deadly enmity between the two has become the subject of countless works of literature since Cain and Abel. On the other hand, it is difficult to prove historically that two or even more sons per father can be peacefully accommodated in the adult sector of their society (HEINSOHN GUNNAR. 2006: 21).

Younger sons usually receive a smaller share of the inheritance and a lower social status compared to their elders, which is seen as unfair. Unable to change anything in the family, the younger ones begin to look for their own paths to success. Under certain conditions, such young men, dissatisfied with their fate, may have an inordinately large proportion in any society and this is manifested in a demographic phenomenon called youth bulges, which can be translated as “youth bulge.” By uniting in groups, these young people gain confidence in their strength and embark on risky, adventurous ventures in order to achieve quick success. Gunnar Heinsohn associates the activity of the Portuguese and Spaniards during the period of geographical discovery with this phenomenon, which took place on the Perinean Peninsula at the end of the 15th century. Moreover, such activity of young people has occurred more than once in the history of mankind. Filled with energy and ambition, "the overabundance of young men is as likely to lead, as always, to bloody expansions as to the making and destruction of empires" (Ibid: 11). Using numerous examples from different times for different peoples, he proves this thesis and it looks quite convincing.

Such an imbalance in the demographic structure of the population of the Northern Black Sea region could have occurred during a period of relatively calm times in Eastern Europe due to an increase in the birth rate and a decrease in mortality among young people. Not finding the use of their energy in peaceful labor, young people found the opportunity to enrich themselves in predatory campaigns in accordance with the traits of their national character. To avoid criminal liability from the authorities, they created their settlements in secluded and inaccessible places. This became the birth of the Cossacks, in which all asocial elements from different places in Europe began to seek refuge. All these are assumptions that still require confirmation.

The study of onomastics can only give an approximate idea of socio-historical processes, but it can raise questions, the answers to which can be sought by comparing historical facts. According to onomastics, the Circassians preferred to settle in Western Ukraine, where a chain of Adyghe toponyms leads and leads directly to Lviv. In this chain, there is Halych, whose name may come from the cab. γăl'ăgn "to elevate", the meaning of which fits well with the name of the capital of the Principality of Halych. In this chain, there are place names that, to varying degrees, can also be deciphered using the Kabardian language: Burshtyn, Konyushki, Babukhiv, Degova, Zhirova, Kaguyiv, Shchirets, Navaria. It can be assumed that it was the Circassians who laid the foundations of the principality even before the arrival of the Ukrainians here.

Another chain of Circassian place names passes through the eastern part of the country, which testifies to the continuation of the history of the Bosporan kingdom. It was multinational and attracted immigrants from different sides. Although the Kurds played a leading role in the state, the Circassians were supposed to be present in it, but their aristocracy was more concentrated in Olbia. The names of some cities of the Bosporan kingdom can be deciphered using the Baltic languages (Pantikapaeus, Patreus, Anapa, etc.), which should indicate the presence of immigrants from the Baltic states. Their presence is also reflected in anthroponymy. The proper names of people deciphered with the help of the Baltic languages, can be found in the dark places of the creation of ancient historians and epigraphs left by participants or witnesses of real events, such as Αρτινοιη, Βαλωδισ, Κυρηακοσ, Παταικοσ, Σαυαγεσ, a.o.

The topic migration of the Baltic tribes is considered separately, but here we will only point out that the Kuban Balts have not lost touch with their ancestral home and the path they laid here from the Baltic could be used by other peoples. The experience of previous studies has shown that people leave their traces on migration routes in toponyms. Therefore, the path originally laid by the Balts is marked with place names of various origins. Among them are Kabardian, mixed with Baltic and Kurdish. Below is a small list of them in the direction from south to north:

Staroleushkovskaya, a rural settlement in Pavlovsky district of Krasnodar Krai, Russia – Kab. leuž` “trail”.

Pishvanov, a hamlet in Zernogradsky district of Rostov Region, Russia – Kab. păš “room”, uăn "to fall, crash".

Azhinov, a hamlet in the Bagaevsky district of the Rostov Region, Russia – Kab. ažă “goat”, nă “eye”),

Sambek, a village in Neklinovsky district of Rostov Region, Russia – Kab. samă “heap”, băq` "barn".

Shchotove, an urban-type settlement in Rovenky district of Luhansk Region, Ukraine – Kab. šč'yt “ditch”.

Fashchivka, an urban-type settlement in Antratsyt district of Luhansk Region, Ukraine – see above.

Fashchivka, an urban-type settlement in Perevalsk district of Luhansk Region, Ukraine – see above.

Hluboka Makatykha, a village in Sviatohirsk urban comunity in Kramatorsk district of Donetsk Region – Kab. măqu "hay", `ătă "stack".

Lypchanivka – see above.

Chuhuiv – see above.

Mezenivka, a village in Sumy district of Sumy Region – Kab. măz “forest“, en “whole“).

Karyzha village in Glushkovsky district of Kursk Region, Russia – Kab. (k`ăryžyn “to leak“),

Shalyhine – see above

Zhykhove (ž`yxu “fan“, out of ž`y “wind“)

Unecha, a town in Bryansk Region (unăšč`a “emptied“).

Hizhenka, an agrotown in Slavharad district of Mogilev Region, Belarus – Kab. (xyž'ăn "become bold"),

Sharypy Bolshiye, a village within the Savsky village council of the Goretsky district of the Mogilev Region, Belarus – Kab. (šăryp' “mammal“).

Not far from the city of Velikiye Luki in the Pskov region of Russia, this chain ends with a cluster of toponyms of Circassian origin in the same place where there is a cluster of sites of one of the variants of the Pskov long mounds culture. Sites of the second variant of this culture are widespread in large numbers south of Lake Pskov, where there is a cluster of places names of Kurdish origin. The time of the appearance of the Kurds in these places is determined by the mention of one of the Kurdish towns in the chronicle in a description of the arrival of the Varangians in Rus`. This happened in the ninth century, meaning the Kurds arrived there even earlier. The existence of the Long Barrow culture dates back to the 5th – 11th centuries, but its ethnicity remains unknown. The correspondence of Kurdish and Circassian toponymy to its different variants allows us to connect the origin of this culture with the massive arrival of Kurds and Circassians to these places. Then the question arises of what made them leave their country and set out in search of new convenient places to settle. The answer may be that at the end of the 4th century, the Huns invaded the Black Sea region and provoked the Great Migration of Peoples. The Bosporan kingdom ceased to exist precisely because the most active part of its population chose not to resist the warlike Huns and disperse in different directions. The Circassians and Kurds moved the same path, but in different groups, and the Circassians went first, so they advanced further. It was in the Velikiye Luki region that the Circassians chose this place for a permanent settlement. Examples of Adyghe place names in the basin of the Velikaya River can be the following:

Alol', villages in Kuderev volost of Bezhanitsky district and in Alol' volost in Pustoshkinsky district of Pskov Region, a river, the tributary of the Velikaya River – Kab. 'ălu "wildly", -lă, adjective suffix.

Khalamer'e, a village in Gorodoksky district, Vitebsk region of Belarus – Kab. hălă-m "heavy" (-m – ergative ending), eruuă "cruel".

Komsha, a village of Velikoluksky district in Pskov Region – Kab. qom “plenty”, šăd "swamp".

Kurmeli, a village in Velizhsky District of Smplensk Region – Kab. kurmă "knot at the end of the string", -lă, adjective suffix.

Nevel, a town and the administrative center of Nevelsky district in Pskov Region – Kab. nă "yey", uălij "ruler, lord".

Opochka, a town and the administrative center of Opochetsky district in Pskov Region – Kab. upIyshkIua "crumpled".

Reble, a village in Pustoshkinsky district of Pskov Region – Kab. eru "fierce, cruel", blă "snake".

Sebezh, a town and the administrative center of Sebezhsky district in Pskov Region – Kab. să "knife", băǯ "spider". The subtle meanings of these words may make it possible to combine them in one name.

Tekhomichi, a village in Sebezhsky district of Pskov Region – Kab. thă "god", myščă "bear".

Usmyn', a villlage in Kunyinsky district of Pskov Region – Kab. uăs "snow", myin "small".

Velizh, a town and the administrative center of Velizhsky district in Smolensk Region – Kab. uălij "ruler, lord" (from Akkadian) -zh' is the noun suffix that reinforces meaning.

V'ar'movo, a village in Krasnogorodsky district in Pskov Region – Kab. ueram "street".

Zhadro, a village in Zvonsk volost, Opochetsky district of Pskov Region – Kab. ǯăd "hen", -ru is the object suffix.

Zhiguli, villages in Verkhnyadzvinsk District of Vitebsk Region, Belarus, and in Kunyinsky District of Pskov Region – Kab. zhigeile "an area overgrown with oak trees". Zhiguli on the Volga of the same origin.

The last place name is found several times in Russia, and in the vicinity of other toponyms of possible Circassian origin. However, there are not so many of them to make hasty conclusions without additional information. However, there is no doubt that the history of the Circassians is rich in various events and requires careful study. First of all, the question arises as to why the Circassians as an ethnic group were assimilated and did not survive as an ethnic group in Ukraine. The answers may be different depending on what events took place in the Northern Black Sea region after the invasion of the Huns and before the arrival of the Ukrainians. From time to time the Russians appeared here, making their campaigns against Constantinople. From the chronicles, it is known that they were in conflict with the Pechenegs, but there are no reports about the Circassians, although they could also take part in these conflicts if they remained in the Black Sea steppes. It all depends on the relationship between the Circassians and the Pechenegs. When the Polovtsians appeared in the steppes, they pushed the Pechenegs into the Crimea, as evidenced by the Chechen toponymy in the Crimea (see Pechenegs and Magyars). The Circassians could have settled among the Ukrainians in the forest-steppe zone even earlier and assimilated among them, being in smaller numbers. In any case, studying the Circassian influence on the Ukrainian language can provide an answer about the future fate of the Circassians in Ukraine.